All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Acute Compartment Syndrome of the Limbs: Current Concepts and Management

Abstract

Acute compartment syndrome (ACS) of the limb refers to a constellation of symptoms, which occur following a rise in the pressure inside a limb muscle compartment. A failure or delay in recognising ACS almost invariably results in adverse outcomes for patients. Unrecognised ACS can leave patients with nonviable limbs requiring amputation and can also be life–threatening. Several clinical features indicate ACS. Where diagnosis is unclear there are several techniques for measuring intracompartmental pressure described in this review. As early diagnosis and fasciotomy are known to be the best determinants of good outcomes, it is important that surgeons are aware of the features that make this diagnosis likely. This clinical review discusses current knowledge on the relevant clinical anatomy, aetiology, pathophysiology, risk factors, clinical features, diagnostic procedures and management of an acute presentation of compartment syndrome.

1. INTRODUCTION

Acute compartment syndrome (ACS) of the limb refers to a constellation of symptoms, which occur following a rise in the pressure inside a limb muscle compartment. A failure or delay in recognising ACS almost invariably results in adverse outcomes for patients. Unrecognised ACS can leave patient with nonviable limbs requiring amputation and can also be life–threatening. Schwartz et al., reported a mortality rate of 47% in patients with ACS of the thigh [1]. Adverse patient outcomes due to delayed or missed diagnosis also have significant medico-legal ramifications for surgeons. A study of 23 years of records on closed malpractice claims found that the average indemnity payment in the United States was $426 000 in addition to a mean cost of $29 500 to defend each case [2].

Compartment syndromes can arise in any area of the body that has little or no capacity for tissue expansion, such as the abdomen, buttocks and hands [3]. It is also important to note that presentations of compartment syndrome are not always acute, but may be sub-acute and at times chronic. However, in this clinical review only the relevant clinical anatomy, aetiology, pathophysiology, risk factors, clinical features, diagnostic procedures and management of an acute presentation of limb compartment syndrome are discussed.

2. CLINICAL ANATOMY

It has been thought for over a century that an increase in pressure was a central mechanism in the evolution of ACS through the early work of von Volkmann [5]. These early ideas have since been refined by increased anatomical knowledge and diagnostic techniques. Within the limbs, muscles are organised into tightly packed compartments, each containing muscle, arteries, nerves and lymphatic vessels and surrounded by an inelastic connective tissue sheath. This sheath limits the extent to which a compartment can accommodate an increase in the volume of its contents. Hence, conditions which either increase the volume of compartmental contents or decrease the capacity of the compartment e.g. through external compression, increase the intracompartmental pressure (ICP).

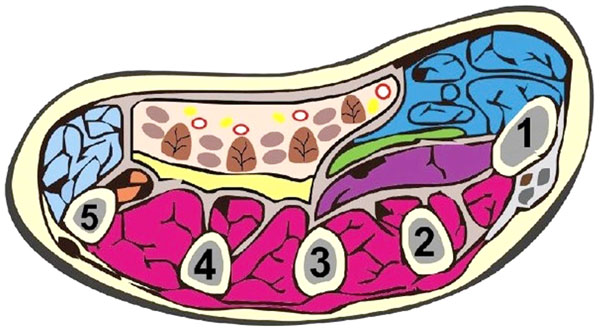

Understanding the actions of the muscles in each muscle compartment may allow the localisation of affected compartment by clinical examination and may guide incision placement. Table 1 summarises the contents of the major limb compartments [6, 7]. The feet and hands are complex structures, which may require specialist attention. There are 10 and 9 compartments in the hand (Fig. 1) and foot respectively [4, 8]. Of note, there is no consensus regarding the number of foot compartments [9]. Only three compartments traverse the entire length of the foot whilst five are confined only to the forefoot [9].

| Anatomical Location | Compartment | Contents |

|---|---|---|

| Upper arm | Anterior |

Muscles: forearm flexors Nerves: radial, median, ulnar nerves |

| Posterior | Muscles: triceps | |

| Forearm | Anterior (superficial and deep) | Muscles: wrist and finger flexors |

| Posterior | Muscles: wrist and finger extensors | |

| Mobile wad |

Muscles: brachioradialis, extensor carpi radialis longus and extensor carpi radialis brevis Nerve: radial nerve |

|

| Thigh | Anterior |

Muscles: knee extensors and hip flexors Nerve: femoral nerve |

| Posterior |

Muscles: knee flexors and hip extensors. Nerve: Sciatic nerve |

|

| Medial |

Muscles: hip adductors Nerve: obturator nerve |

|

| Calf | Anterior |

Muscles: dorsiflexors of the foot Nerve: deep peroneal nerve |

| Lateral/peroneal |

Muscles: foot evertors, plantar flexion Nerve: superficial fibular nerve |

|

| Posterior (deep and superficial) |

Muscles: plantar flexors Nerve: tibial nerve |

Schematic showing the 10 compartments of the hand: thenar (blue), hypothenar (light blue), adductor policis, and the four dorsal interossei (purple) and three volar interossei (cream). This diagram was reused from Chandraprakasam and Kumar [4] which allows fair reuse under the Creative Commons Licence.

3. AETIOLOGY

The causes of ACS either increase the volume of the contents of a compartment or reduce the capacity/volume of the compartment sheath (Box 1) [10]. These two processes can occur either in isolation or concurrently [11]. Causes of a decrease in compartment size include tight dressings, bandages or casts [12]. In some cases, lying on a limb for prolonged periods has been implicated [13]. It is therefore important for clinicians to be particularly alert in patients who have had periods of prolonged unconsciousness, such as drug users [14]. Several papers have also reported the occurrence of ACS after operations, which require unnatural positioning of the patient such as some gynaecological conditions requiring the lithotomy position [15-19]. Patients with circumferential burns to the limbs are also at risk of ACS if they develop an inelastic eschar which prevents tissue expansion during swelling [20]. In such patients, an escharotomy may be initially indicated.

There are several conditions that increase the volume of compartmental contents. Several series have demonstrated that fractures are the most common cause of ACS, accounting for as much as 69% of cases [21, 22]. Fractures of the tibial shaft occur most commonly, followed by distal radius and ulna fractures [6]. Tissue swelling and haematoma formation secondary to the fracture are possible mechanisms by which ICP is elevated after a fracture [23]. Importantly, there is no difference between the ICPs of open and closed fractures meaning that all types of fractures need to be carefully monitored for signs of ACS [24]. This significant finding dispels traditional teaching that open fractures naturally decompress and may not be as prone to compartment syndrome as closed fractures. The small, transverse fascial tears that usually result from open fractures do not adequately decompress the compartment [25].

|

Causes of Compartment Syndrome. Constructed from Shadgan [10]

Conditions that increase compartment contents

Fracture, soft tissue injury, crush syndrome, revascularisation, exercise, fluid infusion, arterial puncture, ruptured ganglia/cyst, osteotomy, snake bite, nephrotic syndrome, leukaemia infusion, viral myositis, acute haematogenous osteomyelitis

Conditions that reduce compartment volume

Burns, casts, repair of muscle hernia, circumferential dressings |

Whereas fractures usually result in the injury of multiple blood vessels of varying size, vascular injuries of a single blood vessel can also cause ICS by causing compartmental ischemia. Injuries to the popliteal artery have a particularly high incidence of ACS [26]. In this setting, the inflammatory response to the initial ischaemic insult can initiate pressure rises, which can be exacerbated by reperfusion. It is thought that reperfusion leads to the initiation of an inflammatory response against the breakdown products of ischaemic tissue, causing cellular and tissue oedema [23].

Arterial injuries may be the mechanism by which blunt trauma results in ACS [27]. Patients with blunt trauma to the limbs therefore require careful and meticulous serial examination of the peripheral vascular system. Vigilance is required in examining patients with arterial injuries as these injuries can cause ACS even in the absence of a fracture [28]. Rarely, common injuries such as ankle inversion injuries have resulted in arterial disruption sufficient to cause ACS [29]. Several reports have also shown that venous insults, such as deep venous thrombosis, can also cause ACS [30]. Care of these patients should ideally, at least, be shared with a vascular surgery firm.

Injuries to soft tissue are another important cause of ACS responsible for as much as 23% of cases in some series [21]. Crush injuries without fractures occur when continuous external compressive forces are applied to a compartment, resulting in traumatic muscle breakdown (rhabdomyolysis). Once tissue necrosis occurs, inflammation ensues. One of the cardinal features of inflammation, tumour, is soft tissue swelling which results in a rise in ICP. Blunt trauma is the leading cause of ACS of the thigh, accounting for as much as 90% of reported cases [31]. Crush injuries can also result in ACS by causing blood vessel damage, initiating the processes described above. Patients with bleeding diatheses are particularly prone to ACS from crush injuries by haematoma formation [21, 32-34]. Several other mechanisms of soft tissue expansion have been described and include bites from a wide range of animals including wasps and snakes [35-37].

The aetiology of ACS can also be iatrogenic. It is known that trans-radial angiography and intervention can result in compartment syndrome if the radial artery perforates and bleeds [38]. However, there has been a reported case where ACS after trans-radial intervention was not due to bleeding or hematoma formation [39]. It was thought to be due to either arterial spasm induced by the radial sheath or catheter resulted in ischemia of the forearm muscles. Bicipital compartment syndrome has also occurred due to malpositioning of a non-invasive blood pressure cuff across the elbow with subsequent flexion of the elbow joint [40].

4. PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

There are several theories to explain the pathophysiology of ACS. Matsen and Krugmire’s widely accepted theory aims to explain the impairment of microcirculation that occurs in ACS [41]. It suggests that the causes of ACS raise ICP and consequently, intraluminal venous pressure. Circulation of blood from high pressure arteries to low pressure veins is dependent on the pressure differential between these vessels (arteriovenous (AV) gradient). A diminished AV gradient has two main implications: there is a decrease in the rates of both delivery of oxygenated arterial blood and drainage of deoxygenated venous blood. Slow or decreased venous drainage results in the extrusion of fluid into the muscle interstitium, causing tissue oedema, which exacerbates the ICP rise. This establishes a vicious cycle, which leads to the collapse of the lymphatics and eventually, the arterial supply leading to ischaemia and irreversible necrosis. Nerve symptoms such as paraesthesia and tingling begin as early as 30 minutes from the onset of ischemia and irreversible damage may occur as early as 12 hours post-onset [6]. The haste at which irreversible changes occur presents a diagnostic challenge to surgeons whose overriding goal is to identify limbs at risk before irreversible tissue changes occur.

An alternative theory to the AV gradient theory is the Critical Closing Pressure Theory (CCPT). The CCPT suggest that because arteriolar luminal radius is small and the walls have a high amount of tension, arterioles require a high arteriolar-tissue pressure gradient is required to maintain their patency [42]. The causes of ACS either raise tissue pressure or reduce arteriolar pressure, removing or reducing the arteriolar-tissue pressure gradient and leading to arteriolar collapse. However, this theory has been discredited in a study where the individual responses of arterioles, capillaries, and post-capillary venules of different diameters where subjected to external forces as can happen in ACS [43]. This study found that although arteriolar flow ceased at mean external pressures of 25.6±2.4, 28.3±2.8, 34.5±4.6, and 44.4±6.8 mm Hg in vessels with diameters of less than 20, 20-40, 40-60, and >60 micrometres, respectively, there were no signs of arteriolar spasm or collapse even at a pressure maximum of 70 mm Hg. However, this study used skinfold chamber model in Syrian golden hamsters, perhaps limiting its direct applicability to human beings.

5. RISK FACTORS

Whilst clinical vigilance is best maintained at all times, it may be helpful, especially for junior surgeons, to characterise a typical ACS patient. The study by McQueen et al., is often cited for this purpose [21]. In this study, the authors retrospectively analysed their case notes between 1988 and 1995, identifying all adults with ACS but excluding those with post-ischaemic ACS, as they were cared for by the vascular surgeons. This study likely shows a true epidemiological picture of ACS because their centre was the sole trauma unit serving a catchment population of 650 000. They found a total of 164 cases (mean age = 32) of whom the vast majority (90.9%) were male. The mean age for men was 30 years and 44 years for women. Men were 10 times more likely to suffer ACS than women. As a result, McQueen et al. recommended that certain patients whose characteristics make them more susceptible should receive compartment pressure monitoring (Box 2). In summary, the typical patient with ACS is a man younger than 35 years of age and has been involved in a high energy sport or traffic collision resulting in a tibial shaft fracture [11, 21].

|

Patients Requiring Extra Clinical Vigilance

|

It is also important to note that the diagnosis of ACS in children may be delayed for reasons including communication difficulties [22]. One study found that the mean time from admission to the fasciotomy in children was 27.9 hours [22]. Considering that irreversible nerve damage can occur within 12 hours of the initial insult, such a length of time may expose children to adverse outcomes. Particular attention must be given to any corroborative history and careful serial examination of extremities carried out.

6. CLINICAL FEATURES

Although the clinical features can be vague and nonspecific, the initial suspicion of a diagnosis of ACS is largely a clinical one. Clinical diagnosis is aided by some classic features including pain, pallor, pulselessness, paraesthesia, pressure, poikilothermia and paralysis [7]. ACS is a dynamic process with incremental damage if it remains undiagnosed. Therefore, it may be beneficial for one experienced assessor to serially examine the patient so the evolution of the condition is noted rather than at one point in time [11, 44]. If a patient has all the five features, this may indicate a late diagnosis and irreversible damage because some features such as paralysis occur very late in the pathogenesis of ACS. The goal of serial assessment is to detect progression towards a more catastrophic clinical state and to intervene quickly enough to allow functional recovery.

These cardinal features should not be considered in isolation but must be interpreted in light of the patient’s personal risk. For example, a 20 year old man with a tibial fracture from a rugby injury complaining of disproportionate pain and none of the other cardinal features should still be treated with a high index of suspicion. The likelihood ratio of such a patient developing ACS has been estimated at approximately 25% assuming a prevalence of 5% [45]. Disproportionate pain, either with passive stretch or at rest, is the classic description of ACS pain and warrants close monitoring at least. However, in the late stages of ACS pain can be absent [11]. Paraesthesia indicates early nerve ischaemia, which progresses to anaesthesia without intervention. Paresis/paralysis are late features which may indicate both nerve and muscular malfunction [11]. Pulselessness and pallor are also late findings, which indicate severe arterial compromise. Palpation of an affected limb may reveal a ‘tight’ swollen limb but palpation even by senior experienced surgeons is not very sensitive for critical ICP rises [44].

The predictive values of the cardinal features have been investigated by Ulmer in a widely cited article [45]. In this study, Bayes’ theorem was used to calculate the predictive values of the following features of ACS: pain, paraesthesia, paresis and pain on passive movement. All features were more specific than they were sensitive: mean specificity 0.97 (range 0.97-0.98) vs means sensitivity 0.16 (range 0.13-0.19). The positive predictive values ranged from 0.11 to 0.15 and all negative predictive values were 0.98. The high specificity and negative predictive values suggest that in the absence of these cardinal features, it is less likely that the patient has ACS. The low positive predictive value suggests that these symptoms on their own are poor indicators of ACS. However, Ulmer also showed that the odds of ACS increase when more than one clinical feature is present. The odds of ACS with two, three and four clinical features are 68%, 93% and 98% respectively [45]. In patients in whom the diagnosis is suspected clinically, several methods of measuring ICP exist.

7. DIAGNOSTIC ADJUNCTS

The diagnosis of ACS should be made as soon as possible after onset and ideally before irreversible damage occurs. Irreversible muscle necrosis can occur as early as 3 hours after the onset of ischaemia and hence, a high suspicion index needs to be maintained [46]. In cases where the clinical features are unequivocal, emergent fasciotomy is indicated. However, as discussed above, a clinical diagnosis may be difficult to reach, necessitating the use of diagnostic adjuncts. There are several types of diagnostic adjuncts of varying invasiveness including pressure measurements, biomarkers and imaging techniques. An understanding of the pathophysiology of ACS is required to allow selection of the most appropriate adjunct depending on the pathological state of the limb.

The pressure of a normal myofascial compartment is usually quoted to be less than 10 mm Hg. Some authors have stated that an absolute ICP of 30 mm Hg is an indication for fasciotomy due to studies showing that ICP sustained at this level for 6-8 hours results in irreversible damage [47]. However, others have argued that ICP should be related to the systemic diastolic pressure to determine the critical pressure (also called Δp) [48]. There is some controversy regarding the threshold of Δp at which surgical intervention is warranted but is usually quoted to be between 30mmHg and 45mmHg. However, several studies have shown that Δp is a more reliable threshold on which to base therapeutic decisions. Instruments for measuring ICP include the Stryker Quick Pressure Monitor Instrument, manometric IV pump method, the Whitesides Infusion Technique [49] and the slit catheter technique [50]. The Stryker instrument and the IV pump method have been found to give accurate and reliable measurements of ICP [51] whereas the Whitesides method gave unreliable results in more than one study [51, 52]. Advantages of the Stryker system is that it is handheld and does not require complex equipment for it operation [53].

There are also several non-invasive imaging techniques for determining ICP. These include near-Infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) ultrasonic devices and laser Doppler flowmetry [54-58]. These non-invasive techniques may be particularly useful in paediatric injuries. For example, NIRS has been demonstrated in infants as young as one month old in whom invasive monitoring may not be ideal [59]. Near-infrared spectroscopy and Laser Doppler Flowmetry may have more utility in chronic compartment syndrome. NIRS measures variations in muscle oxygenation and may be of little value in acute CS where changes in the relative oxygenation may have already occurred by the time measurements are taken [60]. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) has a limited role in ACS diagnosis because although it can oedema and compartment swelling, it only shows late changes, potentially delaying diagnosis [53].

Several biomarkers such as white cell count, creatine kinase (CK) and myoglobin can also be used in the workup of ACS but are not specific [53]. There is as yet no specific biomarker for skeletal muscle ischaemia. Other methods that have been described include Thallium stress testing which is not yet in routine clinical use [61]. It is beyond the scope of this review to describe each of these techniques as this has done extensively elsewhere [53]. It is important to note, however, that whichever technique is used to determine the ICP, the clinical features should suggest indication and the results interpreted with the clinical features in mind. We reiterate the statement by Malik et al., that, in most cases, the diagnosis of ACS should be made on clinical grounds [7].

8. MANAGEMENT

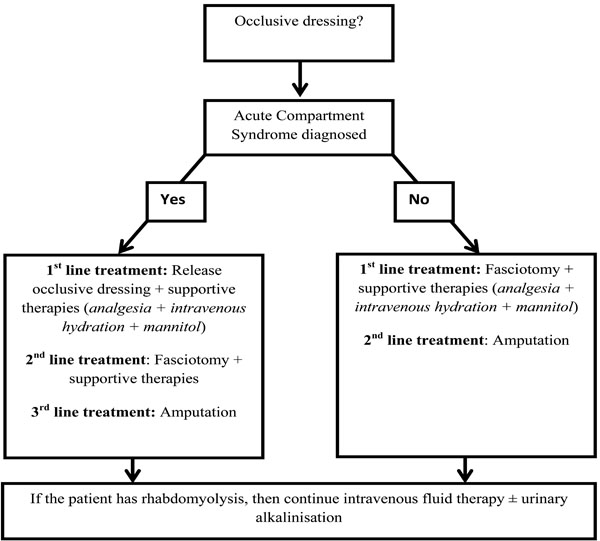

No guidelines for the management of ACS have been published in the United Kingdom (UK) although those from Australia are available [63]. However, the British Medical Journal’s Evidence Centre provides an evidence based algorithm, summarised below and as a diagram in Fig. (2) [62].

Suggested management algorithm for acute compartment syndrome. This figure was constructed by summarising the guidelines from the BMJ Evidence Centre [62].

8.1. Initial Management

Initial management involves removing any dressings overlying the compartment suspected of raised ICP. One study investigated the effect on ICP of first splitting the cast and then cutting the padding in the limbs of 26 dogs with padded plaster casts [64]. It was found that just cutting the plaster reduced ICP by a mean of 65% with an additional 10-20% reduction after the padding was cut. However, as all limbs in this study retained some ICP elevation, the authors concluded that even after removal of tight casts, evaluation for clinical features of ACS was to be continued. The limb should not be elevated but be maintained at heart level to perfuse the compartment [65].

8.2. Fasciotomy

If clinical features of ACS do not regress following this, fasciotomy may be indicated as an emergency procedure. Early suggestion of fascial decompression was by Murphy in 1914 who suggested that a 3-6 inch antero-ulnar fascial incision would result in sufficient decompress the volar forearm compartment [66]. Bardenheuer may have been the first to suggest fasciotomy as a method of treating ACS in 1906 [4]. However, some papers have credited Jepson with pioneering fascial decompression [7] although his description of this approach was only published in 1926, 12 years after Murphy and 20 years after Bardenheuer. It is important to note there are circumstances in which fasciotomy may not be indicated, for example in patients who already have muscle death due muscle crush syndrome suffered in situations such as natural disasters [67]. Conservative management may be more appropriate in these patients.

As no consensus currently exists on a particular pressure at which fasciotomy is absolutely indicated, the decision to proceed should be based on a comprehensive clinical assessment. Mubarak and Hargens suggest that fasciotomy is indicated in the following circumstances [68]:

- Hypotensive patients with ICPs of greater than 20 mm Hg

- Uncooperative or unconscious patients with ICPs greater than 30 mm Hg

- Normotensive patients with positive clinical findings, who have compartment pressures of greater than 30 mm Hg, and whose duration of increased pressure is unknown or thought to be longer than 8 hours. However, the BMJ Evidence Centre’s management algorithm (summarised in Fig. 1) quotes Olson and Glasgow [69] who suggest that where there “is clinical evidence of ACS with a probable duration of more than 8 hours, with absence of muscle function in a neurologically intact limb, primary amputation rather than fasciotomy should be considered [62].”

Once the decision to operate has been made, it is important that a fasciotomy with incisions large enough to adequately decompress affected compartments is performed. Table 2 summarises information from the literature regarding optimum scar placement and surgical approaches to the common presentations of ACS in different parts of the limbs.

Incisional Approaches to Different Compartments

| Compartments | Incisions |

|---|---|

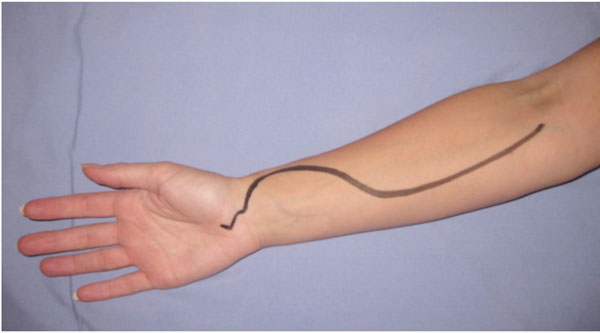

| Forearm | All forearm compartments can be decompressed using two incisions: the preferred volar incision (Fig. 3) and dorsal incisions which are sometimes performed concurrently [6, 7] . |

| Hand | Although not a true compartment, the carpal tunnel is a closed space and needs to be decompressed [70]. In some series, all patients underwent carpal tunnel decompression as well as decompression on individual interossii [71]. Incision placements for interossii decompression are shown in Fig. (4). Mid-lateral incisions on the non-dominant or noncontact side can be used for digital decompression are shown in figure [4]. |

| Thigh | More patients are treated with a single incision than with two incisions (86% versus 14%) [31]. A single lateral incision (Fig. 5) allows adequate decompression of all three compartments but two parallel fascia lata incisions are sometimes used to prevent muscle herniation [6]. No comparative studies have been attempted. For lateral and posterior ACS, incisions begin around the intertrochanteric line extending to the lateral epicondyle [31]. |

| Lower leg | The surgeon may perform either a single lateral incision or concurrent medial and lateral incisions (Fig. 6), both of which should be a minimum of 15 cm [7]. Where the patient has sustained a tibial fracture, a single incision is recommended as double incisions may reduce soft tissue support, compromising the stability of the fracture [72]. |

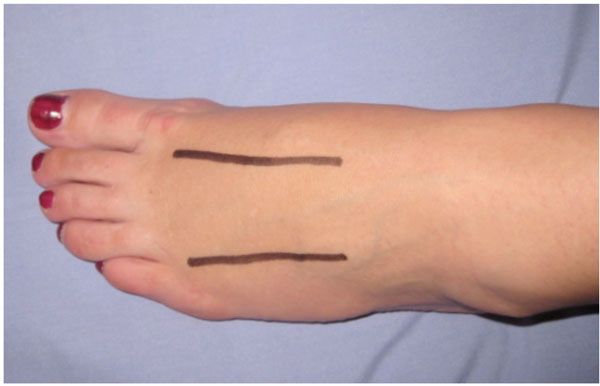

| Foot | Generally includes two dorsal incisions over the second to fourth metatarsals for decompressing the forefoot compartments (Fig. 7), a medial incision for decompressing the calcaneal, medial and superficial compartments and a lateral incision, beginning at the lateral malleolus extending to the forefoot between the fourth and fifth metatarsals, for decompressing the lateral compartments [9, 73] . |

Although there is no consensus regarding the optimum timing of wound closure [6], primary closure of the wound is not commonly performed [7]. In a systematic review of all reported cases series on thigh ACS, most patients (59%) received delayed primary closure of the fasciotomy incision whilst only 15% received primary closure [31]. The remaining 26% received split thickness skin grafts. Delaying closure for about seven days allows wound edges approximation at closure [31]. Also, there may be need for repeat irrigation and debridement before final wound closure. There may be a role for various adjuncts and techniques developed to increase the rate of skin closure such as vacuum-assisted closure and shoelace suturing techniques [6].

Incision placement for release of the volar forearm compartment syndrome. The incision must also allow decompression of the carpal tunnel.

8.3. Postoperative and Supportive Care

Pain is a major feature of ACS and adequate analgesia should be prescribed. The surgeon should then monitor the patient for the development of complications of ACS in the acute stage. Muscle necrosis or rhabdomyolysis may lead to the accumulation of myoglobin in the kidneys, causing acute renal failure in up to 50% of patients with rhabdomyolysis [74]. Patients should therefore be adequately hydrated to achieve a target urinary output of at least 0.5 mL/kg [62]. There is some debate in the literature on the utility of mannitol as an adjunct in treating ACS. There is some evidence that mannitol may reduce ICP and be a useful adjunct in ischaemic-reperfusion injuries [75, 76]. However, interestingly, there have been reported cases where intravenous mannitol administration has resulted in ACS through extravasation [77]. Adequate hydration is also important as a treatment for rhabdomyolysis. Serial measurements of CK can be made to assess the response to hydration therapy in rhabdomyolysis.

Incision placements for decompressing interossei compartments.

A single lateral incision allows adequate decompression of all three thigh compartments.

Leg compartments can be decompressed from medial and lateral incisions which can either be placed concurrently or singularly. They should be a minimum of 15 cm.

The incision placement shows two dorsal incisions over the second to fourth metatarsals for decompressing the forefoot compartments. A medial incision can be used to decompress the calcaneal, medial and superficial compartments and a lateral incision, beginning at the lateral malleolus extending to the forefoot between the fourth and fifth metatarsals can be used to decompress the lateral compartments.

CONCLUSIONS

This review summarises current knowledge on the aetiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis and management of acute compartment syndrome. The several techniques of measuring intracompartmental pressures are also discussed. The importance of early diagnosis and intervention is emphasised with observations that early fasciotomy not only improves patient outcome but is also associated with decreased risk of indemnity [2].

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.