All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Epidemiology of Knee and Hip Arthroplasty: A Systematic Review§

Abstract

We present a systematic review of epidemiologic studies of Total Knee Arthroplasty (TKA) and Total Hip Arthroplasty (THA). The studies summarized in this systematic review provide us with estimates of arthroplasty utilization rates, underlying disease frequency and its trends and differences in utilization rates by age, gender and ethnicity among other factors. Among these, many studies are registry-based that assessed utilization rates using data from major orthopedic centers that may provide some understanding of underlying diagnosis and possibly time-trends. Several studies are population-based cross-sectional, which provide estimates of prevalence of TKA and THA. Population-based cohort studies included in this review provide the best estimates of incidence and utilization rates, time-trends and differences in these rates by important patient characteristics (age, gender, ethnicity and others). This article reviews the current published literature in the area and highlights the main findings.

INTRODUCTION

Joint arthroplasty constitutes a major advance in the treatment of chronic refractory joint pain. It is indicated in patients for whom conservative medical therapy has failed. Total Knee and Total Hip Arthroplasty (TKA and THA) are two common surgeries that reduce pain and improve function and quality of life in patients with knee and hip disorders [1-5]. Osteoarthritis is the commonest underlying condition for both TKA and THA. Other conditions leading to TKA and THA include inflammatory arthritis, fracture, dysplasia, malignancy and others. Though there are some differences in outcomes of TKA and THA due to differences in anatomy of the joint and underlying disease conditions [6], most patients achieve significant long-lasting improvement with these procedures.

Due to significant benefits realized with TKA THA, the utilization rates of these procedures have been increasing. In recent years, many studies have examined the incidence and prevalence of knee and hip arthroplasty. The main purpose of this study was to perform a systematic review of studies that examined the prevalence and incidence rates for TKA and THA. Our second aim was to summarize reported differences related to age, gender or race for these procedures.

§The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

METHODS

Five databases were searched on 09/02/2009 using the key terms “knee/hip arthroplasty”, “knee/hip joint replacement” “knee/hip replacement” “total knee/hip arthroplasty” AND “epidemiology” or “prevalence” or “incidence” or “prevalence rate” or “incidence rate”. The databases included: [1] The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), via The Cochrane Library, Wiley InterScience (www.thecochranelibrary.com), current issue; [2] OVID MEDLINE, 1966-present; [3] CINAHL (via EBSCOHost), 1982-present; [4] OVID SPO RTdiscus, 1949-present ; and [5] Science Citation Index (Web of Science) 1945-present. The list of titles was further narrowed to make it specific to epidemiology of arthroplasty, and not the complications of arthroplasty by expert librarians (LM, JB).

All titles and abstracts were screened by an experienced epidemiologist (J.S.) with expertise in performing systematic reviews. The criteria for including a study were that: (1) it assessed either prevalence or incidence rate; and (2) it was a published article. Studies were excluded if they were abstracts, focused on complications of arthroplasty, or were related to arthroscopy. Studies were grouped into those that examined the rates of knee versus hip and primary versus revision arthroplasty.

Simple estimates such as annual utilization, prevalence and incidence rates are presented. Rates across countries were to be combined to get an overall estimate, if they had been performed during a similar time-period.

RESULTS

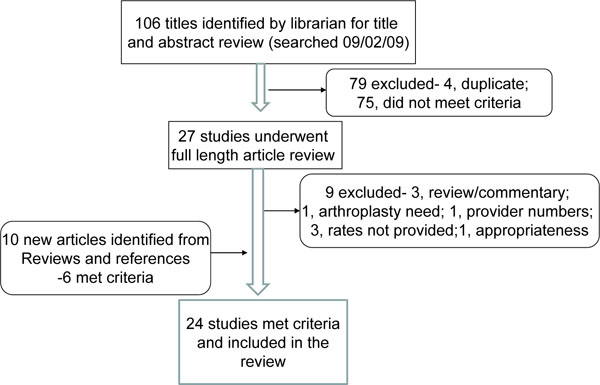

Two expert librarians (L.M., J.B.) performed a focused search of five databases for epidemiology of THA and TKA, which identified 106 relevant studies: 34 Medline, 13 CINAHL, 8 Web of science, 4 SportDiscus, 47 CENTRAL. Of these 106 titles and abstracts, four were duplicates and were removed. The PI (J.S.) reviewed titles and abstracts of the remaining 102 studies, of which 27 qualified for the full text review (Fig. 1). Of these, nine studies were excluded: three were reviews or commentaries; one addressed need, but not rates of arthroplasty; one addressed current and future provider-patient ratios; three did not provide prevalence/incidence rates; one addressed appropriateness of THA/TKA. Eighteen studies from the original search met the inclusion and exclusion criteria [7-24]. An additional six studies were identified from the reference lists of included studies [25-30]. Thus, 24 studies were included in the systematic review.

Flow chart of included studies.

Overview of Epidemiology Studies

Table1 summarizes the salient features and the man findings of each study included in this review. A few epidemiology studies were performed in population-based samples [7-13, 25-26]. Most other studies of epidemiology of THA and/or TKA were performed in non-population hospital-based cohorts. Age-standardization was performed for most population-based studies, except one [13]. Similarly, most registry-based epidemiology studies were also age-standardized. Most studies were performed in Europe, North America and Australia. Several studies examined time trends in arthroplasty rates over the last few decades, while others examined the arthroplasty utilization rates by age groups, gender and ethnicity. Disparity in utilization rates of THA and TKA by ethnicity, gender, rural/urban residence and region has been described.

Summary of Findings from Included Studies

| Study | Country | Years Studied | Population/Setting | Type of Study | Type | Rate | Age Standardized | Registry-Based |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population-based studies of THA and TKA | ||||||||

| 1. Ingvarsson, 1999 [7] | Iceland | 1982-1996 | Population-based | Cohort | THA for osteoarthritis (OA) | 1996: 40-49 yrs: 17/100,000 50-59 yrs: 97/100,000 60-69 yrs: 333/100,000 70-79 yrs: 499/100,000 80+ yrs: 314/100,000 |

Yes | No |

| 2. Lohmander 2006 [8] | Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden | 1996-2000 | Population-based | Cohort | Primary THA for primary hip OA | All: 61-84/100,000 F: 60-92/100,000 M: 48-75/100,000 |

Yes | Yes |

| 3. Pedersen 2005 [9] | Denmark | 1996-2002 | Population-based | Cohort | Primary and revision THA | Incidence rate, 1996: Prim THA: 101/100,000 Rev THA: 19/100,000 Incidence rate, 2002: Prim THA: 131/100,000 Rev THA: 21/100,000 |

Yes | Yes |

| 4. Steel 2006 [10] | U.K. | 2002 | Population-based: people ≥60 yrs, representative of the population of England interviewed | Cross-sectional | THA or TKA | Lifetime prevalence of THA or TKA : F: 6% M: 5% |

No | No |

| 5. Robertsson 2000 [11] | Sweden | 1976-1997 | Population-based | Cohort | primary and revision TKAs | Incidence rate, 1976: Prim TKA, all: 13/100,000 F: 18/100,000 M: 7/100,000 Incidence rate, 1997: Prim TKA, all: 63/100,000 F: 69/100,000 M: 35/100,000 |

Yes | Yes |

| 6. Coyte 1997 [12] | Ontario, Canada | 1984-1990 | TKAs performed in Ontario from the Canadian Institute for Health Information | Cohort | TKA | Utilization rates: 1984 to 1990 F: 24/100,000 to 52/100,000 M: 11/100,000 to 33/100,000 |

Yes | No |

| 7. Melton 1982 [25] | Olmsted County, U.S. | 1969-1980 | THAs performed in Olmsted county, Minnesota | Cohort | THA | Biennial Incidence rates: 1969-1970: 20/100,000 1971-1972: 45/100,000 1973-74: 48/100,000 1975-76: 43/100,000 1977-78: 54/100,000 1979-80: 54/100,000 F: 52/100,000 M: 34/100,000 |

Yes | Yes |

| 8. Johnsson 1987 [26] | Southern Sweden | 1981-82 | THA in nine Southern most units in Sweden | Cohorts | THA | Hip Replacement (THA and hemi-arthroplasty): 26/10,000 for adults aged 49 and older |

Yes | Yes |

| 9. Wells 2002 [13] | Australia | 1994-1998 | Population-based: all Australians underwent THA and TKA for the principal diagnosis of osteoarthritis |

Cohort | THA and TKA for OA | 1994: Prim THA: 51/100,000 Prim TKA: 56/100,000 1998: Prim THA: 61/100,000 Prim TKA: 77/100,000 |

No | No |

| Registry/National Database Based THA Studies | ||||||||

| 10. Abbott 2003 [14] | U.S. | 1995-1999 | 2000 United States Renal Data System | Cohort | THA | 35 per 10,000 person-years compared to 5.3/10,000 in the general population |

No | No |

| 11. Clark 2001 [15] | U.S. | 1987-1996 | Army aviators 214,300 aviator-years of observation |

Cohort | THA | 0.05/1,000 aviator years of observation (11 aviators with 14 THAs) |

No | Yes |

| 12. Kim 2008 [16] | South Korea | 2002-2006 | National Database with reimbursement records from all South Korean medical facilities |

Cross-sectional | THA | 2002: F: 1.7/100,000 M: 1.4/100,000 2005: F: 3.1/100,000 M: 2/100,000 |

Yes | Yes |

| 13. Birrell 1999 , [27] | England | 1996 | Hospital Episode System (HES) for identification of all THAs |

Cross-sectional | THA | 1996: All: 87/100,000 F: 109/100,000 M: 65/100,000 |

No | No |

| 14. Hoaglund 1995 und, F. T. [28] |

San Francisco, U.S. | 1984-1988 | Hospital records from 17 hospitals in “San Francisco country” |

Cross-sectional | THA for primary hip OA | White: 76/100,000 Black: 35/100,000 Hispanic: 13/100,000 Filipino: 7/100,000 Japanese: 17/100,000 Chinese: 8/100,000 |

Yes | No |

| 15. Puolakka 2001 [29] | Finland | 1999 | Cohort | THA | 1999: Prim THA: 93/100,000Rev THA: 23/100,000 | No | Yes | |

| Registry/National Database Based TKA Studies | ||||||||

| 16. Mehrotra 2005 [17] | U.S. | 1990-2000 | Wisconsin Inpatient Hospital Database for Wisconsin residents ≥45 years | Cross-sectional | Primary TKA | 1990: All (age-standardized): 162/100,00 F: 30/100,000 M: 23/100,000 2000: All (age-standardized): : 294/100,000 F: 46/100,000 M: 35/1000,000 |

Yes | No |

| 17. Kim 2008 [18] | South Korea | 2002-2005 | National Database with reimbursement records from all South Korean medical facilities | Cross-sectional | TKA | 2002: F: 85/100,000 M: 10/100,000 2005: F: 157/100,000 M: 20/100,000 |

Yes | Yes |

| 18. Juni 2003 [19] | U.K. | 1994-95 | Survey of 40 clinical practices in Somerset and Avon, UK of 26,046 people | Cross-Sectional | TKA | 8.4/1,000 for TKA for subjects ≥35 years M: 5.5/1,000 F: 10.7/1,000 |

No | No |

| 19. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2009 [20] | U.S. | 2000 & 2006 | Medicare enrollees aged ≥65 years, not members of Health Maintenance organizations and entitled to Medicare part A 2000: 26,585,955 2006: 28,382,683 |

Cross-sectional | TKA | 2000: 5.5/1,000 2006: 8.7/1,000 Racial Disparity: Whites: 5.7/1,000 in 2000 and 9.2/1,000 in 2006 Blacks: 3.6/1,000 in 2000 and 5.6/1,000 in 2006 Male: 4.6 in 2000, 7.3 in 2006 Female: 6.1 in 2000, 9.8 in 2006 |

Yes | No |

| Registry/National Database Based THA and TKA Studies | ||||||||

| 20. Jarvholm 2007 [21] | Sweden | 1960-1992 | Construction worker cohort participating in national health control program from |

Cohort | THA & TKA | Ranged between professions from 447-857/million person-years for THA, 123-407/million person-years for TKA |

Yes | Yes |

| 21. Kurtz 2007 [22] | U.S. | 1990-2002 | National Hospital Discharge Survey (NHDS), a representative sample of all non-federal non-military in-patient facilities |

Cross-sectional | THA and TKA | 1990: Prim THA: 47/100,000 Rev THA: 9.5/100,000 Prim TKA: 51/100,000 Rev TKA: 4.7/100,000 2002: Prim THA: 69/100,000 Rev THA: 15.2/100,000 Prim TKA: 136/100,000 Rev TKA: 12.5/100,000 |

Yes | No |

| 22. Melzer 2003 [23] | U.S. | 1993 | 1993 National Mortality Follow back Survey in people ≥65 years, who had THA or TKA <1 year from their death |

Cross-sectional | TKA and THA | Prevalence: THA: 15.5% TKA: 6% |

No | No |

| 23. Wells 2004 [24] | Australia | 1994-2002 | Male Veterans compared with male civilians for THA and TKA for OA in Southern Australia |

Cohort | THA and TKA for OA |

THA: Standardized morbidity ratio (SMR)- 0.715 TKA: SMR-0.987 |

Yes | Yes |

| 24. Havelin 2000 [30] | Norway | 1997 | Norwegian register established 1988 | Cohort | THA | 1997: prim THA: 120/100,000 Rev THA: 24/100,000 Prim TKA: 34/100,000 |

||

THA, Total Hip Arthroplasty; TKA, Total Knee Arthroplasty; OA, osteoarthritis, F, female; M, male; Prim, primary; Rev, revision.

Time Trends in Knee Arthroplasty

The number of hospitalizations for TKA among U.S. Medicare enrollees increased from 145,242 in 2000 to 248,267 in 2006, an increase by 58% [20]. This translated into an overall TKA incidence rate increase from 5.5 to 8.7 per 1,000 population [20].

In a U.S. study, Kurtz et al. used the National Hospital Discharge Survey (NHDS) to study rates of primary and revision THA and TKA [22]. Primary TKA rates increased 170% from 51/100,000 to 136/100,000 and revision TKA rated increased by 270% from 4.7/100,000 to 12.5/100,000.

In an analysis of Wisconsin residents 45 years and older from 1990-2000 using the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) dataset, Mehrotra et al. found 1.5 times higher rate for TKA in 2000 [17]. The youngest age group, 45-49 had the largest growth in rate from 9/100,000 to 46/100,000 for men and 17/100,000 to 71/100,000 for women from 1990 to 2000 [17].

In a study of trends from the Swedish Register, the rates of primary TKA increased by 5-fold in a 20-year period of observation [11], with similar increases for men and women. While yearly incidence rates for arthroplasties performed for osteoarthritis increased, it remained unchanged for rheumatoid arthritis [11].

Time Trends in Hip Arthroplasty

Kurtz et al. found a significant increase in annual rates of primary and revision THA from 1990 to 2002 in the U.S. NHDS [22]. There was a 50% increase in primary THA rate from 47/100,000 to 69/100,000 and a 60% increase in revision THA rate from 9.5/100,000 to 15.2/100,000.

In a study of time-trends in THA in Iceland, the total number of THAs increased from 94 THAs in 1982 to 323 THAs in 1996 [7]. The annual incidence increased from 43 to 133 per 100,000 people, an increase by 3-fold. The annual incidence of THA for primary osteoarthritis per 100,000 increased 68 in 1982-86 to 114 in 1992-1996. Annual incidence of revision THA increased from 2.5 per 100,000 in 1982 to 25 per 100,000 in 1996 [7].

In a population-based study in Denmark, the incidence rates of primary and revision THA increased by 30% (101 to 131 per 100,000) by 10% (19.2 to 20.7 per 100,000) from 1996 to 2002 [9]. The increase in primary THAs was noted in all age groups, but was highest for patients aged 50-59 and lowest for those aged 10-49 [9]. An increase in incidence rates from 1996 to 2002 was noted for all diagnoses including osteoarthritis, except rheumatoid arthritis, for which the incidence rate decreased [9].

In a study using the Hospital Episode System in England, rate of THA was estimated at 87/100,000 in 1996, slightly higher in women (109/100,000) than men (64/100,000) [27]. Projection of time-trend revealed that a 40% increase in THA rates would be noted by year 2030, with higher increase in men (51%) than women (33%) [27].

Age Differences in Arthroplasty Rates

In a U.S. study of Medicare recipients comparing the rates of TKA between 2000 and 2006, rates in patients aged 65-74, 75-84 and ≥85 years (all rates per 1,000 population) were 5.4, 6.6 and 2.6 in 2000; and 9.1, 10.2 and 4.0 in 2006, respectively [20].

Disparity in Arthroplasty Utilization

A variety of factors have been associated with disparity in the rates of knee and hip arthroplasty. Following is a summary of current evidence supporting the existence of disparity in utilization of arthroplasty.

Race/Ethnicity:

In a U.S., study, Caucasians had TKA rates of 5.7 and 9.2 per 1,000 and African-Americans had rates of 3.6 and 5.6 per 1,000, respectively [20]. The TKA rates were 37% lower among blacks than whites in 2000 and 39% lower in 2006. In both years, the ethnic/racial disparity was lower among women (23% and 28%) than among men (63% and 60%) [20].

Caucasians had the highest annual age-standardized rates of THA in San Francisco residents in a study from 1984-88 [28]. Blacks, Japanese, Hispanics, Chinese and Filipino had lower rates in decreasing order compared to Caucasians.

Gender:

Three studies reported similar increase in utilization rates between men and women undergoing arthroplasty. In a U.S. study using the NIS, the increase was noted both for women and men at a similar rate [17]. In a Danish study, the increase in THA incidence rates from 1996 to 2002 were similar in men and women [9]. In a study of nationally representative sample of 7,100 people aged ≥60 years from England, similar rates of existing knee or hip joint replacement were reported for women (6%) and men (5%) [10]. In a U.S. Medicare study, women had TKA utilization rates of 6.1 and 9.9 in 2000 and 2006; respective rates in men were 4.6 and 7.3, respectively [20]. In a national study from South Korea, women had more severe knee disease, higher BMI and were 7-8 times more likely to undergo TKA than men [18].

Region:

A study from England found lower prevalence of existing knee or hip joint replacement for Northern compared to Southern region, although the need was significantly greater in North compared to South [10]. In the same study, the need was greater in women and increased from wealthiest to poorest quintile, but receipt did not differ by sex or socio-economic group. Melton et al. examined THA utilization rates in Olmsted County, Minnesota, USA from 1969 to 1980 [25]. Adjusted THA rates were lower in rural than urban residents of Olmsted County, 29/100,000 versus 49/100,000, respectively. Similarly, a study in Ontario, Canada found differences in TKA rates between different parts of Ontario [12] with Southern Ontario regions having significantly higher provincial population than the provincial population.

Veteran Status:

One Study compared rates of TKA and THA between Veterans and civilians in Southern Australia between 1994 and 2002 [24]. The overall rates were similar for TKA, but significantly lower in veterans for THA versus civilians. Veterans in age group 65-74 were less likely, and those in age groups 75-84 and ≥85 years more likely than civilians to have THA [24].

Rates of utilization could not be pooled across countries due to a wide variation in rates, time-periods and presentation of data for different groups.

CONCLUSION

In this systematic review of the literature, we found that the utilization rates for THA and TKA have increased over the last 2-3 decades. With aging of the population and increased longevity, the TKA and THA utilization rates are projected to increase even further. The rates vary by country of study, which may be due to differences in socioeconomic status, health care delivery systems, patient preferences and/or prevalence of osteoarthritis, the most common underlying cause for THA/TKA. A few studies have been performed on a population-level, providing information on prevalence and incidence, but more work is needed in this area. Disparities have been noted based on ethnicity, gender and region. While important advances have been made in arthroplasty outcomes, equity remains a challenge. Future studies should examine the causes of these disparities and test interventions that can reduce the disparities in use of THA and TKA.

NOTES

§ The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I thank Lisa McGuire and Jim Beattie from the Medical library at the University of Minnesota for performing the searches.

Grant Support:

NIH CTSA Award 1 KL2 RR024151-01 (Mayo Clinic Center for Clinical and Translational Research) and the Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Mayo Clinic School of Medicine, Rochester, MN.

Financial Conflict:

There are no financial conflicts related to this work. J.A.S. has received speaker honoraria from Abbott; research and travel grants from Allergan, Takeda, Savient, Wyeth and Amgen; and consultant fees from Savient and URL pharmaceuticals.