All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Prognostic Significance Of Serum Urea Concentration at Admission in older patients with hip fracture

Abstract

Background:

There are unmet needs in objective prognostic indicators for Hip Fracture (HF) outcomes.

Objectives:

To evaluate the determinants and prognostic impact of elevated serum urea, a key factor of nitrogen homeostasis, in predicting hospital mortality, inflammatory complications and length of stay in HF patients.

Methods:

In 1819 patients (mean age 82.8±8.1 years; 76.4% women) with osteoporotic HF, serum urea level at admission along with 22 clinical and 35 laboratory variables were analysed and outcomes recorded. The results were validated in a cohort of 455 HF patients (age 82.1±8.0 years, 72.1% women).

Results:

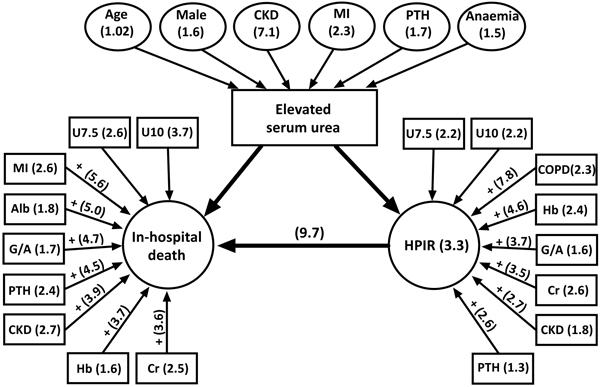

Elevated serum urea levels (>7.5mmol/L) at admission were prevalent (44%), independently determined by chronic kidney disease, history of myocardial infarction, anaemia, hyperparathyroidism, advanced age and male gender, and significantly associated with higher mortality (9.4% vs. 3.3%, p<0.001), developing a high postoperative inflammatory response (HPIR, 22.1% vs.12.1%, p=0.009) and prolonged hospital stay (>20 days: 31.2% vs. 26.2%, p=0.021). The predictive value of urea was superior to other risk factors, most of which lost their discriminative ability when urea levels were normal. Patients with two abnormal parameters at admission, compared to subjects with the normal ones, had 3.6-5.6 -fold higher risk for hospital mortality, 2.7-7.8-fold increase in risk for HPIR and 1.3-1.7-fold higher risk for prolonged hospital stay. Patients with increased admission urea and a high inflammatory response had 9.7 times greater mortality odds compared to patients without such characteristics.

Conclusion:

In hip fracture patients admission serum urea is an independent and valuable predictor of hospital outcomes, in particular, mortality.

1. INTRODUCTION

In the last two decades, serum urea concentration, the terminal product of protein metabolism, received much attention as a simple and reliable biochemical parameter for predicting adverse outcomes, especially short- and long-term mortality, in various medical and surgical settings including cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, respiratory, liver, pancreatic, septic and critically ill patients [1-11]. Elevated urea has been shown to be an independent and a better prognostic indicator of mortality than the Glomerular Filtration Rate (GFR) and creatinine in patients with acute and chronic cardiovascular diseases [2, 5-7, 12, 13].

However, the value of urea for risk stratification of hospital outcomes in Hip Fracture (HF) patients has not been evaluated systematically. Reports on the prognostic significance of serum urea level in HF patients are limited, conflicting and focussed only on predicting mortality [14-18]. Moreover, although liver is the main ureagenic organ and routine hepatocyte function parameters (albumin levels, enzyme activities) have been found to be valuable prognostic indicators for poor outcomes in HF patients [19-22], no study was performed on the relationship between serum urea, liver function characteristics at admission and outcomes in HF.

The aims of this study were to assess in a representative sample of older HF patients (1) the prevalence and determinants of elevated serum urea level at admission, (2) its association with short-term outcomes, and (3) the potential prognostic impact alone and in combination with clinical and other biochemical characteristics, focussing on liver-specific and protein metabolism-related variables.

2. PATIENTS AND METHODS

2.1. Patients

This study is based on prospectively collected socio-demographic, clinical (comorbidities, complications, medication used, hospital outcomes) and laboratory data on consecutive patients with Hip Fracture (HF) admitted to the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery of the Canberra Hospital (university-affiliated 672-bed tertiary care center) from January 2000 to January 2013. Patients who had high trauma or subtrochanteric fracture as well as pathological HF due to primary or metastatic bone cancer, multiple myeloma, Paget disease or primary hyperparathyroidism, or who had incomplete data on admission were excluded. In total, 1819 older (≥60 years of age) patients (mean age 82.8±8.1 years; 76.4% women; 94.6% Caucasian) with low-trauma osteoporotic HF were finally included in the study.

The study was approved by the Australian Capital Territory Health Human Research Ethical Committee and waived the requirement for written consent as only routinely collected and anonymized before analysis data were used.

2.2. Validation Dataset

A retrospective analysis of a second cohort included data (obtained from electronic medical and administrative records) from 455 consecutive older (≥60 years of age) patients (mean age 82.1 ± 8.0 years, 72.1% women) with osteoporotic HF who were treated at the Canberra Hospital between 2013 and 2015.

2.3. Laboratory Tests

In each patient, fasting venous blood samples were collected on admission and the following assays performed: urea and electrolytes, complete blood count, C-Reactive Protein (CRP), liver (Alanine aminotransferase [ALT], Gamma-Glutamyl Transferase [GGT], alkaline phosphatase [ALP], bilirubin and albumin) and thyroid (thyroid stimulating hormone [TSH], and free thyroxine [T4]) function tests, 25 (OH) vitamin D [(25(OH)D], intact parathyroid hormone (PTH) and indices of iron metabolism (iron, ferritin, transferrin, Transferrin Saturation [TSAT]) using standard methods and commercially available kits as we described previously [20]. In all patients, glomerular filtration rate (GFR, by standardized serum creatinine-based formula normalized to a body surface area of 1.73 m2) was estimated. Chronic kidney disease (CKD, ≥stage 3) was defined as a GFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2. The cut-off level for elevated serum urea was set at >7.5mmol/L (upper limit of normal range). The cut-offs selected by other researchers varied between 5 and 15.4mmol/L, but in most studies were between 5 and 10.0mmol/L [7, 18, 23-28], therefore, we also analysed the effects of urea>10.0mmol/L. Deficiency of vitamin D was defined as 25(OH)D < 25nmol/l and insufficiency as 25(OH)D < 50nmol/l. Hyperparathyroidism (SHPT) was defined as elevated serum PTH (>6.8pmol/l). In total, 22 clinical and 35 biochemical and haematological variables were analysed in relation to admission serum urea concentration and its prognostic and predictive value.

2.4. Outcomes

The main postoperative outcomes studied were: (1) in-hospital mortality, (2) complications associated with a High Postoperative Inflammatory Response (HPIR) defined as CRP>150mg/L after the 3rd postoperative day and (3) Length Of Stay (LOS).

2.5. Statistical Analyses

All continuous variables are expressed as mean ± Standard Deviation (SD) and compared using analysis of variance; categorical parameters are presented as frequency (percentage) and compared by Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests. The associations between urea at admission with each other studied variable (continuous and categorical) and with hospital outcomes were assessed using Pearson’s correlation coefficients (log-transformed variables), univariate and multivariate logistic regression models. Potential confounding variables (demographic, clinical and laboratory) with statistical significance ≤ 0.100 in the univariate analysis were included in multivariate models to identify independent factors associated with elevated admission urea and with hospital outcomes. Data are presented with 95% Confidence Intervals (CI). The final predicting models were developed by stepwise logistic regression. The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test was used to assess model performance. To quantify the significance of multicollinearity phenomena in regression analyses the variance inflation factor was calculated.

The individual predictive abilities of urea levels, other laboratory and clinical parameters of interest were evaluated by the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analyses and the accuracy was expressed as area under curve (AUC); the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive values (PPV), negative predictive values (NPV), accuracy, positive likelihood ratio (LR+), and negative likelihood ratio (LR−) were also calculated. Similarly, we assessed the predictive performances of any two eligible variables combined (pairs). Statistical significance was accepted at the p<0.05 level (two-tailed). All statistical analyses were performed using the Stata software version 10 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Clinical Characteristics of Patients With and Without Elevated Urea at Admission

The patients’ socio-demographic, clinical and laboratory characteristics and short-term outcomes categorised by serum urea at admission are shown in Table 1. Urea levels were elevated in 800 (44.0%) HF patients, and in both genders, these patients were older (on average +2.6 years for females and +5.4 years for males); men were significantly younger than women, but the difference in mean age in the group with increased urea was 1.5 years vs. 5.3 years in the group with normal urea. Patients with elevated urea compared to those with normal urea levels were more likely to be admitted from a permanent Residential Care Facility (RCF), more commonly had a history of CKD, hypertension, Coronary Artery Disease (CAD), Myocardial Infarction (MI), anaemia and diabetes mellitus type 2 (DM), but were less likely to have previously a Cerebrovascular Accident (CVA), to be current smokers or alcohol over-users (>3 times per week). There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of 7 other chronic comorbidities and lifestyle factors, including HF type and dementia. Among 35 laboratory parameters tested, 7 demonstrated statistical significance. Patients with elevated urea compared to those with normal urea, in addition to expected worse renal function (higher creatinine levels, lower GFR) had significantly higher levels of PTH, ALP and 25(OH)D and lower bilirubin concentrations (Table 1).

3.2. Determinants of Elevated Serum Urea Levels at Admission

Multivariate logistic regression analysis adjusting for all of the univariate clinical and laboratory variables associated with elevated serum urea on admission (with p≤0.100), as well as for HF type and pre-admission use of any diuretics (frusemide, thiazides, spironolactone), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin 2-receptor blockers, revealed as significant and independent correlates of urea>7.5mmol/L the following six factors: CKD, history of MI, anaemia, hyperparathyroidism, advanced age and male gender (Table 2).

| Variables |

All patients (n=1819) |

Urea>7.5 mmol/L (n=800) | Urea≤7.5 mmol/L (n=1019) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||||

| Females | 83.4±7.7 | 84.9±7.3 | 82.3±7.9 | <0.001 |

| Males | 80.6±9.0 | 83.4±7.2 | 78.0±9.7 | <0.001 |

| Both genders | 82.8±8.1 | 84.5±7.3 | 81.4±8.5 | <0.001 |

| Age >75 years, n (%) | 1511(83.1) | 719(89.9) | 792(77.7) | <0.001 |

| Age >80 years, n (%) | 1288(70.8) | 629(78.6) | 659(64.7) | <0.001 |

| Males/Females, n | 429/1390 | 206/594 | 223/796 | 0.054 |

| From RCF, n (%) | 636(35.0) | 300(37.5) | 336(33.0) | 0.044 |

| CKD, n (%) | 789(43.4) | 566(70.8) | 223(21.9) | <0.001 |

| CAD, n (%) | 49(26.9) | 261(32.6) | 229(22.5) | <0.001 |

| MI, n (%) | 133(7.3) | 84(10.5) | 49(4.8) | <0.001 |

| HT, n (%) | 937(51.5) | 451(56.4) | 486(47.7) | <0.001 |

| Anaemia: | ||||

| Hb<110g/L, n (%) | 355(19.5) | 194(24.3) | 161(15.8) | <0.001 |

| Hb<120g/L, n (%) | 699(38.4) | 370(46.3) | 329(32.3) | <0.001 |

| CVA, n (%) | 219(12.0) | 83(10.4) | 136(13.3) | <0.053 |

| DM, n (%) | 175(9.6) | 92(11.5) | 83(8.1) | 0.016 |

| Smoker, n (%) | 100(5.5) | 33(4.1) | 67(6.6) | 0.024 |

| Alcohol+, n (%) | 92(5.1) | 25(3.1) | 68(6.6) | 0.001 |

| Urea, mmol/L | 8.5±7.4 | 12.4±9.8 | 5.4±1.4 | <0.001 |

| Creatinine, µmol/L | 92.9±60.0 | 119.0±80.3 | 72.3±20.5 | <0.001 |

| GFR, ml/min/1.73m2 | 62.5±22.1 | 49.1±20.5 | 72.9±17.2 | <0.001 |

| PTH, pmol/L | 8.5±7.4 | 10.4±9.1 | 7.1±5.3 | <0.001 |

| 25(OH)D, mmol/L | 48.3±28.8 | 50.3±29.2 | 46.7±28.4 | 0.016 |

| ALP, IU/L | 100.8±70.7 | 106.5±86.7 | 96.3±54.7 | 0.003 |

| Bilirubin, µmol/L | 12.4±8.1 | 11.7±6.8 | 12.9±8.9 | 0.003 |

| Outcomes: | ||||

| LOS, days | 19.0±22.3 | 20.5±25.7 | 17.8±19.2 | 0.011 |

| LOS>20 days, % | 28.4 | 31.2 | 26.2 | 0.021 |

| HPIR, % | 16.5 | 22.1 | 12.1 | 0.012 |

| Died, % | 6.0 | 9.4 | 3.3 | <0.001 |

3.2. Correlations of Urea, Clinical and Other Laboratory Parameters with Outcomes (Pearson Correlation Coefficients)

In Pearson correlation analysis, urea as a log-transformed continuous variable showed stronger correlation with in-hospital death (r=0.181, p<0.001) than log-GFR (r=-0.174, p<0.001), log-creatinine (r=0.169, p<0.001), log-PTH (r=0.145, p<0.001), log-albumin (r=-0.073, p=0.002), log-25(OH)D (r=-0.049, p=0.041) and log-age (r=0.081, p<0.001). Log-urea did not correlate with HPIR (r=0.090, p=0.092) and LOS >20 days (r=0.038, p=0.106), while log-creatinine (r=0.128, p=0.017; r=0.071, p=0.003, respectively) and log-25(OH)D (r=0.118, p=0.031; r=-0.077, p=0.001, respectively) did. However, pairwise comparisons among all abovementioned variables showed, as would be expected, that log-urea significantly correlated with log-creatinine (r =0.634, p<0.001), log-GFR (r =-0.621, p<0.001), log-PTH(r =0.277, p<0.001), log-haemoglobin (r =-0.125, p<0.001), log-25(OH)D (r =0.049, p=0.043) and log-age (r =0.254, p<0.001), but not with log-albumin (r =-0.016, p=0.488) or log-GGT/ALT ratio (r =0.022, p=0.349). All described associations were significant in both males and females when checked separately.

| Variables | OR | 95%CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CKD | 7.08 | 5.61-8.94 | <0.001 |

| History of MI | 2.25 | 1.46-3.48 | <0.001 |

| PTH>6.8 pmol/L | 1.69 | 1.35-2.12 | <0.001 |

| Anaemia (Hb<120g/L) | 1.45 | 1.15-1.83 | 0.002 |

| Gender (male) | 1.63 | 1.25-2.14 | <0.001 |

| Age (year) | 1.02 | 1.00-1.03 | 0.040 |

When we analysed the data as categorical variables, among all clinical and laboratory variables tested, urea >7.5mmol/L demonstrated the third highest Pearson’s correlation coefficient with mortality (r=0.126, p<0.001) comparable to that of creatinine>90µmol/L (r=0.131, p<0.001) and GFR<60ml/min/1.73m2 (r=0.129, p<0.001), and higher than all other parameters, including PTH>6.8pmol/L(r=0.108, p<0.001), 25(OH)D<25nmol/L (r=0.076, p=0.002), albumin <33g/L (r=0.065, p=0.006), GGT/ALT>2.5 (r=0.060, p=0.012), haemoglobin<110g/L (r=0.057, p<0.015), history of MI (r=0.088, p<0.001), COPD (r=0.068, p=0.004), male gender (r=0.045, p=0.053), and age>75 years (r=0.058, p=0.014). Urea >7.5mmol/L and creatinine>90µmol/L were the only two parameters which correlated significantly with each of the three studied outcomes; in addition to in-hospital death, both elevated urea and creatinine were associated with HPIR (r=0.133, p=0.012; r=0.162, p=0.002, respectively) and LOS>20days (r=0.054, p=0.021; r=0.082, p=0.001, respectively). Other parameters associated with HPIR were anaemia (haemoglobin<110g/L, r=0.140, p<0.009) and 25(OH)D<25nmol/L (r=-0.121, p=0.026), whereas LOS>20days correlated with CKD (r=0.065, p=0.006), PTH>6.8pmol/L (r=0.050, p=0.039) and albumin<33g/L (r=0.049, p=0.037). The analysis showed also a significant interaction between in-hospital death and HPIR (r=0.166, p=0.002), but not between mortality and LOS or between HPIR and LOS.

3.3. Urea and Hospital Outcomes (Regression Multivariate Analyses)

Admission urea as a continuous variable (adjusted for age and gender) was significantly associated with in-hospital mortality: for each mmol/L increment in urea concentration the risk of a fatal outcome increased by 3.3% (OR 1.033; 95%CI 1.016-1.050; p<0.001). Other laboratory parameters (as continuous variables adjusted for age and gender) significantly associated with mortality were albumin (OR 0.948; 95%CI 0.917-098; p=0.002), GFR (OR 0.970; 95%CI 0.961-0.980; p<0.001), GGT/ALT ratio (OR 1.049; 95%CI 1.017-1.082; p=0.002), creatinine (OR 1.005; 95%CI 1.003-1.007; p<0.001) and ALT (OR 1.002; 95%CI 1.000-1.004; p=0.042). None of these biochemical variables was significantly associated with HPIR, but admission concentrations of albumin (OR 0.978; 95%CI 0.961—0.996; p<0.015) and creatinine (OR 1.002; 95%CI 1.000-1.004; p<0.021) were indicative for LOS>20 days.

Serum urea on admission >7.5mmol/L was found in 76(69.7%) of 109 non-survivors [in 51(46.8%) of them urea was >10mmol/L], in 177(59.0%) of 300 patients with a HPIR and in 254 (49.1%) of 517 patients with LOS>20 days. In comparison to individuals with normal urea, patients with urea above 7.5mmol/L evidenced adverse in-hospital outcomes (Tables 1 and 3): significantly higher mortality rates (9.4% vs. 3.3%, OR 2.60, p<0.001), higher incidence of HPIR (22.1% vs.12.1%, OR 2.21, p=0.009), prolonged hospital stay (+2.7 days, p=0.011) and a higher proportion of long-stayers (>20 days: 31.2% vs. 26.2%, p=0.021, OR 1.20, p=0.087); all presented ORs were adjusted for age and gender. Analysis of the urea/albumin ratio>5.5(median) showed that this parameter was no better than urea>7.5mmol/L for predicting risks of mortality (OR 2.64, 95%CI 1.69-4.14, p<0.001) or HPIR (OR 1.96, 95%CI 1.09-3.54, p=0.025).

| Model |

Urea 7.5 -10.0 mmol/L (n=410) |

Urea >10.0 mmol/L (n=390) |

Urea >7.5 mmol/L (n=800) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | |

| In-hospital mortality | |||||||||

| 1 | 1.82 | 1.07-3.10 | 0.028 | 4.41 | 2.80-6.96 | <0.001 | 3.00 | 1.98-4.54 | <0.001 |

| 2 | 1.62 | 1.02-2.78 | 0.049 | 3.70 | 2.31-5.91 | <0.001 | 2.60 | 1.70-3.98 | <0.001 |

| 3 | 1.52 | 0.91-2.87 | 0.102 | 1.96 | 1.03-3.73 | 0.041 | 1.82 | 1.07-3.10 | 0.027 |

| 4 | 4.09 | 1.05-22.43 | 0.05 | 6.62 | 1.32-33.16 | 0.021 | 3.10 | 1.03-10.16 | 0.044 |

| High postoperative inflammatory response (HPIR) | |||||||||

| 1 | 1.82 | 1.02-3.61 | 0.046 | 2.17 | 1.06-4.43 | 0.034 | 2.05 | 1.16-3.64 | 0.014 |

| 2 | 2.17 | 1.06-4.43 | 0.034 | 1.91 | 1.02-3.90 | 0.04 | 2.21 | 1.21-4.01 | 0.009 |

| 3 | 2.15 | 0.99-4.73 | 0.052 | 2.12 | 1.02-3.02 | 0.041 | 2.18 | 1.07-4.42 | 0.031 |

After further adjustments for potential confounders known to be associated with poor outcomes (all variables with p value≤0.100 on univariate analysis) including history of CKD, MI, DM, COPD, anaemia, albumin<33g/L, GGT/ALT>2.5, PTH>6.8pmol/L and 25(OH)D<25nmol/L, the significant relationships remained between admission urea >7.5mmol/L and hospital mortality (OR 1.82, p=0.027) as well as with HPIR (OR 2.18, p=0.031); in a fully adjusted model elevated urea failed to identify patients with LOS>20 days (Table 3). In the multivariate analysis, in addition to elevated urea, independent predictors of mortality included history of MI (OR 2.35, 95%CI 1.26-4.38, p=0.007), COPD (OR 2.16, 95%CI 1.24-3.74, p=0.006), albumin<33g/L (OR 2.08, 95%CI 1.28-3.35, p=0.003), 25(OH)D<25nmol/L (OR 1.99, 95%CI 1.26-3.14, p=0.003), CKD (OR 1.80, 95%CI 1.06-3.07, p=0.030), PTH>6.8pmol/L (OR 1.79, 95%CI 1.10-2.91, p=0.019) and GGT/ALT>2.5 (OR 1.64, 95%CI 1.05-2.55, p=0.029); the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness of-fit test indicated good calibration of the model (p=0.853). Independent predictors of HPIR, in addition to elevated urea, were COPD (OR 2.62, 95%CI 1.18-5.84, p=0.018), 25(OH)D<25nmol/L (OR 2.50, 95% 1.09-5.56, p=0.032) and GGT/ALT>2.5 (OR 1.88, 95%CI 1.01-3.50, p=0.047); goodness of-fit test p=0.7258. Independent predictors of LOS>20 days were COPD (OR 1.46, 95%CI 1.01-2.12, p=0.043), albumin<33g/L (OR 1.32, 95CI% 1.01-1.72, p=0.041) and age (OR 1.02, 95%CI 1.00-1.04, p=0.024), but not elevated urea; goodness of-fit test p=0.3996.

We also evaluated in multivariate logistic models (all preoperative parameters with p<0.100 on univariate analysis included) predictors of poor outcomes in the subgroup of patients with admission urea >7.5mmol/L. Independent factors for a fatal outcome in this group were PTH>6.8pmol/L (OR 2.53, 95%CI 1.36-4.69, p=0.003), history of MI (OR 2.47, 95%CI 1.25-4.88, p=0.009) and albumin<33 g/L (OR 2.30, 95%CI 1.29-4.07, p=0.005); the model explained 19.7% of the total variance (R2) in mortality. As independent predictors for HPIR were identified COPD (OR 4.96, 95%CI 1.38-17.81, p=0.014) and anaemia (haemoglobin<110g/L, OR 3.32, 95%CI 1.28-8.63, p=0.014); R2=17.4%. In patients with elevated urea at admission who developed a HPIR the mortality risk increased by 4.6 fold (OR 4.56, 95%CI 1.59-13.07, p=0.005). LOS>20 days was predicted by on admission low transferrin saturation (TSAT<18%, OR 1.72, 95%CI 1.23-2.39, p=0.001), vitamin D insufficiency (25(OH)D<50nmol/L, OR 1.32, 95%CI 1.03-1.70, p=0.027) and advanced age (OR 1.04, 95%CI 1.02-1.05, p<0.001); R2 =5.3%. The persistence of main independent risk factors for hospital outcomes in the total cohort and in patients with raised urea indicates the consistency of our models.

To better characterize the association between preoperative urea levels and postoperative outcomes, patients were categorized into 3 subgroups (Table 3): with normal (<7.5mmol/L, n=1019[56.0%]), moderately increased (7.5 - 10.0mmol/L, n=410 [22.5%]) and high urea levels (>10.0mmol/L, n=390 [21.4%]). In the 3 subgroups, the postoperative mortality rates were 3.3%, 5.8% (OR 1.82, p=0.028), and 13.1% (OR 4.41, p < 0.001), respectively, HPIR developed in 12.6%, 20.7% (OR 1.82, p=0.046), and 21.5% (OR 2.17, p =0.034) of patients, respectively, and LOS>20 days had 26.1%, 30.1% (OR 1.22, p= 0.120), and 32.4% (OR 1.36, p = 0.019), respectively. After adjustments for age and gender, compared to patients with normal admission urea, the risk of a fatal outcome in patients with urea between 7.5 and 10.0mmol/L was 1.6 times higher, and in subjects with urea>10mmol/L was 3.7 times higher being 2.3 times higher than in patients with urea 7.5-10mmol/L (OR 2.34, p=0.001). After further adjustments for all abovementioned confounders, the risk of hospital death for patients with urea 7.5-10 mmol/L was 1.5 times higher (p=0.102) and in subjects with urea>10mmol/L was 2-times higher (p<0.041). Serum urea levels were also significantly associated with the risk of HPIR (the ORs were 2.2 in both groups with urea 7.5 -10mmol/L and >10.0mmol/L). Prolonged hospital stay was associated with admission urea>10mmol/L (OR 1.36, 95%CI 1.05-1.75, p=0.019), but this relationship lost statistical significance after adjustment for age and gender (p=0.087). When the fully adjusted models included also HPIR, the risk of hospital death was 4.1 and 6.6 times higher in patients with admission urea 7.5-10mmol/L and >10mmol/L, respectively (Table 3).

Taken together, the presented data indicate that in older patients with HF even mildly-moderately elevated serum urea at admission is independently and strongly associated with poor outcomes, in particular with in-hospital death and developing a HPIR.

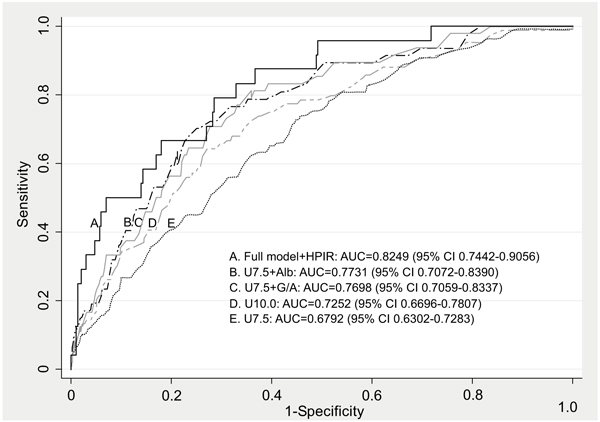

3.4. Predictive Efficacy/Accuracy of Elevated Admission Urea Levels (Single and Combined With Other Variables)

Next we performed ROC analysis (adjusting for age and gender) for elevated admission urea concentration and compared it to abnormal creatinine, GFR, PTH, and albumin levels, GGT/ALT and urea/albumin ratios. For predicting a fatal outcome, urea>10.0mmol/L yielded the best results (the largest AUC value of 0.7252, 95%CI 0.6696-0.7807); the AUC’s for urea>7.5mmol/L (0.6792, 95%CI0.6302-0.7283) and for urea/albumin>5.5 (0.6762) were slightly lower and comparable to those for creatinine>90 µmol/L(0.6823) and GFR<60ml/min/1.73m2 (0.6813), but higher than those for three other on-admission indices (all AUCs <0.6570). The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predicting value (NPV), accuracy, positive likelihood ratio (LR+) and negative likelihood ratio (LR−) were 13.1%, 96.7%, 73.3%, 60.7%, 74.1%, 3.97 and 0.90 at urea >10mmol/L; the corresponding values for admission urea >7.5mmol/L were 9.3%, 96.7%, 57.4%, 69.7%, 56.6%, 2.82 and 0.94%. For predicting HPIR, the best results showed creatinine>90µmol/L (AUC 0.6263) followed by elevated urea (AUC 0.6062). For predicting LOS>20 days, the tested variables demonstrated low discrimination ability (all AUC<0.5648) and elevated urea levels did not reach statistical significance. The level of serum urea 7.5-10.0mmol/L, predicted hospital mortality with 69.5% accuracy and HPIR with 67.4% accuracy, whereas the admission urea >10mmol/L showed an accuracy of 73.3% and 68.1%, respectively.

These results indicated an acceptable AUC value to predict fatal outcome when admission urea >10mmol/L, but the discriminatory performance of other individual parameters [despite being independent and significant prognostic indicators] was low. Therefore, we evaluated in logistic regression models (adjustment for age and gender) whether an approach combining two biomarkers can improve the accuracies of predictions for poor outcomes (Tables. 4 and 5; Fig. 1). Patients with two abnormal parameters at admission, compared to subjects with the normal ones, had 2.9-5.6 -fold higher risk for hospital mortality, 2.6-7.8-fold increase in risk for HPIR and 1.3-1.7-fold higher risk for prolong LOS (Table 4). The mortality rate in patients with both urea and albumin admission levels in the normal ranges was 2.9%, in subjects with only urea>7.5mmol/L - 8.1%, in subjects with only albumin<33g/L - 4.6% and in individuals with both abnormalities - 14.6%.

Admission urea>7.5mmol/L remained a significant indicator of in-hospital mortality even when all other tested clinical and laboratory parameters, except PTH, were normal; the discriminative significance of elevated urea was borderline when accompanied with GFR above 60ml/min/1 (p=0.062). In patients with normal urea at admission all studied clinical and laboratory variables, except CKD, were not relevant in predicting mortality (Table 4). In patients with increased both urea and PTH the mortality risk was 4.5 times higher comparing to patients with these two markers in the normal range, but neither elevated urea, nor high PTH separately were statistically significant indicators for a fatal outcome if the other variable was normal suggesting that the effects of increased urea and PTH on mortality risk are not independent, but co-determined by some metabolic mediators.

Similarly, admission urea>7.5mmol/L was indicative for HPIR when other studied parameters were normal [borderline significance when accompanied by anaemia with haemoglobin>110g/L (p=0.072) or creatinine≤90µmol/L (p=0.099)], whereas in patients with normal urea, COPD, anaemia, hyperparathyroidism and GGT/ALT >2.5 failed as prognostic indicators for HPIR. Combination of elevated urea and low albumin on admission did not achieve statistical significance as an indicator for HPIR (OR 2.2, p=0.159) suggesting opposite roles of these metabolic alterations in developing HPIR.

|

Variables: Urea>7.5 mmol/L plus |

Group 1 (Both variables abnormal) |

Group 2 (Only urea >7.5mmol/L) |

Group 3 (Only the second variable abnormal) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | |

| In-hospital mortality | |||||||||

| +MI | 5.59 | 2.82-11.09 | <0.001 | 2.52 | 1.59-3.98 | <0.001 | 2.53 | 0.85-7.54 | 0.095 |

| +Albumin<33g/L | 4.97 | 2.71-9.12 | <0.001 | 2.56 | 1.54-4.27 | <0.001 | 1.61 | 0.75-3.45 | 0.217 |

| +GGT/ALT>2.5 | 4.65 | 2.51-8.60 | <0.001 | 3.01 | 1.68-5.39 | <0.001 | 1.95 | 0.96-3.96 | 0.066 |

| +PTH>6.8pmol/L | 4.46 | 2.44-8.12 | <0.001 | 1.74 | 0.82-3.66 | 0.148 | 1.53 | 0.74-3.18 | 0.255 |

| +CKD | 3.86 | 2.29-6.51 | <0.001 | 1.97 | 0.97-4.02 | 0.062 | 2.11 | 1.02-4.33 | 0.043 |

| +Hb<110g/L | 3.74 | 2.10-6.64 | <0.001 | 2.31 | 1.42-3.74 | <0.001 | 1.09 | 0.44-2.69 | 0.845 |

| +Creatinine >90µmol/L | 3.55 | 2.17-5.82 | <0.001 | 2.02 | 1.10-3.72 | 0.023 | 1.93 | 0.85-4.39 | 0.115 |

| +Hb<120g/L | 2.88 | 1.65-5.00 | <0.001 | 2.52 | 1.46-4.37 | 0.001 | 1.10 | 0.53-2.26 | 0.795 |

| +HPIR | 9.68 | 3.14-29.83 | <0.001 | 2.89 | 1.04-8.01 | 0.041 | 1.31 | 0.15-11.43 | 0.809 |

| High postoperative inflammatory response (HPIR) | |||||||||

| +COPD | 7.76 | 2.54-23.70 | <0.001 | 2.07 | 1.06-4.04 | 0.032 | 1.74 | 0.58-5.23 | 0.323 |

| +Hb<110g/L | 4.59 | 1.96-10.76 | <0.001 | 1.89 | 0.94-3.77 | 0.072 | 1.75 | 0.59-5.16 | 0.312 |

| +Hb<120g/L | 3.98 | 1.76-9.00 | 0.001 | 2.57 | 1.15-5.75 | 0.022 | 2.75 | 1.14-6.65 | 0.025 |

| +GGT/ALT>2.5 | 3.73 | 1.57-8.88 | 0.003 | 2.40 | 1.08-5.34 | 0.032 | 1.86 | 0.78-4.40 | 0.161 |

| +Creatinine >90µmol/L | 3.48 | 1.66-7.34 | 0.001 | 2.01 | 0.88-4.60 | 0.099 | 2.78 | 1.03-7.50 | 0.044 |

| ++CKD | 2.66 | 1.27-5.55 | 0.009 | 2.75 | 1.13-6.71 | 0.026 | 1.96 | 0.76-5.08 | 0.039 |

| +PTH>6.8pmol/L | 2.62 | 1.15-5.94 | 0.022 | 2.82 | 1.18-7.08 | 0.027 | 1.35 | 0.55-3.33 | 0.510 |

| Length of hospital stay>20 days | |||||||||

| +25(OH)D<50nmol/L | 1.72 | 1.25-2.36 | 0.001 | 1.25 | 0.88-1.77 | 0.215 | 1.45 | 1.07-1.97 | 0.016 |

| +Albumin<33g/L | 1.47 | 1.02-2.11 | 0.041 | 1.24 | 0.98-1.58 | 0.076 | 1.41 | 1.02-1.96 | 0.039 |

| 2+ Creatinine >90µmol/L | 1.39 | 1.08- 1.79 | 0.010 | 1.13 | 0.84-1.51 | 0.408 | 1.56 | 1.05-2.32 | 0.027 |

| + CKD | 1.31 | 1.03-1.68 | 0.030 | 1.05 | 0.76-1.47 | 0.755 | 1.11 | 0.79-1.56 | 0.541 |

The impact of elevated urea combined with other parameters for prognostication LOS>20 days was minimal. The combination of increased urea and vitamin D insufficiency yielded the highest OR (1.72, p<0.001), which was only a little improvement comparable to that of vitamin D insufficiency and normal urea (OR 1.45, p=0.016); likewise, urea combined with hypoalbuminaemia demonstrated ORs of 1.47 and 1.41, respectively (Table 4).

Next, we characterized the association between mortality and HPIR. Compared to patients with normal admission urea, the risk of hospital death in patients with elevated urea who did not developed HPIR was 2.9 times higher (OR 2.89, p<0.041) and 9.7 times higher in patients who experienced both conditions (OR 9.68, p<0.001), but in subjects with normal urea levels at admission HIPR was not predictive for a fatal outcome (OR 1.3, p<0.809) (Table 4). Of note, some combinations have more than an additive effect on outcomes. It appears that co-occurrence of raised urea with history of MI or low albumin or GGT/ALT>2.5 and, especially, with HPIR has synergistic effect on mortality, whereas presence of COPD together with elevated urea demonstrates a synergistic effect on HPIR.

ROC-analyses of hospital death occurrence with each pair of on-admission variables showed that this outcome is best predicted by combination of urea>7.5mmol/L with albumin<33g/L (AUC 0.7731), or with GGT/ALT>2.5 (AUC 0.7698), followed by combination of elevated urea with anaemia (AUC 0.7190) or PTH>6.8pmol/L (AUC 0.7132) or history of MI (AUC 0.7093) or CKD (AUC 0.7079) or creatinine >90µmol/L (AUC 0.7045). Among admission parameters, the highest sensitivity demonstrated the combination of elevated urea with hyperparathyroidism (77.9%) or CKD (74.7%), and the highest specificity showed the combination of urea with history of MI (93.1%) or with hypoalbuminaemia (84.7%) or with anaemia (83.1%). The high NPV (≥95.0%) of all combined characteristics indicate that the number of false positive tests is low. Presence of any two abovementioned characteristics on admission would miss a fatal outcome in 2.5-5.3% of patients with a negative result.

The highest predictive value for HPIR showed the combinations of urea>7.5mmol/L with anaemia (haemoglobin<120g/L, AUC 0.6928) or with creatinine >90µmol/L (AUC 0.6561) or with GGT/ALT>2.5 (AUC 0.6418), indicating a modest-low ability of these combinations to predict HPIR. None of the studied combinations showed a satisfactory predictive value for prolonged LOS (all AUCs under 0.5929).

Elevated urea at admission and HPIR demonstrated the highest discrimination power of predicting a fatal outcome (AUC 0.8176) and the latter result did not differ significantly from that of the full model (8 independent variables at admission and HPIR, AUC 0.8249, 95%CI 0.7442-0.9056, p<0.001) (Table 5, Fig 1).

|

Variables: Urea>7.5 mmol/L plus |

AUC | 95%CI | Se,% | Sp,% | PPV.% | NPV,% | Ac,% | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-hospital mortality | ||||||||

| +Albumin<33g/L | 0.7731 | 0.7072-0.8390 | 51.1 | 84.7 | 14.6 | 97.1 | 83.0 | <0.001 |

| + GGT/ALT>2.5 | 0.7698 | 0.7059-0.8337 | 64.6 | 74.3 | 11.8 | 97.5 | 73.8 | <0.001 |

| +25(OH)D<25nmol/L | 0.7258 | 0.6325-0.8190 | 59.5 | 81.4 | 12.2 | 97.9 | 80.5 | <0.001 |

| +Hb<120g/L | 0.7190 | 0.6588-0.7793 | 50.7 | 66.8 | 10.3 | 94.7 | 65.6 | 0.002 |

| +Hb<110g/L | 0.7180 | 0.6456-0.7904 | 47.2 | 83.1 | 12.9 | 96.7 | 81.3 | <0.001 |

| +PTH>6.8pmol/L | 0.7132 | 0.6569-0.7695 | 77.9 | 58.8 | 11.9 | 97.4 | 60.0 | <0.001 |

| +MI | 0.7093 | 0.6274-0.7913 | 31.8 | 93.1 | 16.7 | 96.9 | 90.5 | <0.001 |

| + CKD | 0.7079 | 0.6539-0.7620 | 74.7 | 60.6 | 11.0 | 97.4 | 61.4 | <0.001 |

| +Creatinine >90µmol/L | 0.7045 | 0.6492-0.7598 | 68.3 | 66.6 | 11.5 | 97.1 | 66.7 | <0.001 |

| +HPIR | 0.8176 | 0.7008-0.9275 | 62.5 | 87.5 | 29.4 | 96.6 | 85.6 | <0.001 |

| High postoperative inflammatory response (HPIR) | ||||||||

| +Hb<120g/L | 0.6928 | 0.5888-0.7968 | 58.1 | 71.8 | 26.1 | 90.9 | 69.8 | 0.001 |

| +Creatinine >90µmol/L | 0.6561 | 0.5695-0.7428 | 57.5 | 68.9 | 25.3 | 89.9 | 67.2 | 0.001 |

| +GGT/ALT>2.5 | 0.6418 | 0.5268-0.7567 | 55.6 | 73.5 | 27.3 | 90.2 | 70.8 | 0.003 |

| +COPD | 0.6389 | 0.5161-0.7617 | 29.6 | 94.3 | 47.1 | 88.8 | 84.9 | <0.001 |

| +Hb<110g/L | 0.6353 | 0.5190-0.7516 | 40.6 | 85.8 | 34.2 | 88.8 | 78.8 | <0.001 |

| +CKD | 0.6250 | 0.5348-0.7152 | 60.0 | 60.2 | 21.4 | 89.3 | 60.2 | 0.018 |

| Length of hospital stay>20 days | ||||||||

| +25(OH)D<50nmol/L | 0.5928 | 0.5500-0.6355 | 64.6 | 49.6 | 34.3 | 77.5 | 53.9 | <0.001 |

| + Creatinine >90µmol/L | 0.5686 | 0.5349-0.6022 | 42.1 | 67.2 | 33.2 | 75.0 | 60.2 | 0.001 |

| + CKD | 0.5683 | 0.5348-0.6018 | 47.8 | 61.0 | 32.9 | 74.5 | 57.2 | 0.003 |

| + Albumin<33g/L | 0.5544 | 0.5254-0.5834 | 21.8 | 84.8 | 34.0 | 75.1 | 68.1 | 0.017 |

Taken together, these results show that the discriminatory performance of elevated urea (alone and combined with other markers) differs for different outcomes and can be used for predicting unfavorable survival outcome and developing HPIR, but not for predicting prolonged LOS.

3.5. Validation

The validation and main cohorts were comparable in mean age, gender distribution, comorbidities, fracture types and outcomes. In the validation cohort, 23(5.1%) of 455 patients died in the hospital, 99 (21.7%) developed HPIR and 93(20.4%) had LOS>20 days. Admission urea>7.5mmol/L (after adjustment for age and gender) was predictive for in-hospital death: OR 3.60, 95%CI 1.45-8.90, p=0.006; AUC 0.7739, 95%CI 0.7045-0.8433; mortality rate: observed 10.3%, predicted 9.4%. Similarly, urea>10.0mmol/L was indicative for a fatal outcome: OR 3.10, 95%CI 1.20-8.03, p=0.020; AUC 0.7179, 95%CI 0.6291-0.8067; mortality rate: observed 11.9%, predicted 13.1%. Among subjects with urea>7.5mmol/L, the observed/predicted proportions of patients who developed HPIR were 23.8%/22.1% and the proportions of individuals with LOS>20 days were 29.0% /31.1%, respectively. Analyses of the prognostic performance of two combined parameters showed also comparable results in the validation and main cohorts. Urea>7.5mmol/L combined with albumin<33g/L yielded an observed/predicted mortality rate of 12.7%/14.4%, combined with GGT/ALT>2.5-15.8%/11.8%, combined with creatinine>90µmol/L-11.3%/11.5%, and combined with PTH>6.8pmol/L-11.8%/11.9%, respectively. These results indicate that the proportion of observed poor outcomes in the validation cohort matched the proportion predicted by elevated urea levels alone and/or in combination with other parameters.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Main Findings

This study based on a relatively large and well defined cohort of older HF patients with parallel assessment of a broad spectrum of clinical and laboratory parameters showed that elevated serum urea levels (>7.5mmol/L) at the time of admission (1) were prevalent (44%), (2) independently determined by CKD, history of MI, anaemia, hyperparathyroidism, advanced age and male gender, and (3) had a substantial impact on prognostication hospital outcomes, in particular, mortality and developing HPIR, being associated with 2.6-fold and 2.2-fold greater odds, respectively. Patients with increased admission urea and HPIR demonstrated almost 10 times greater mortality odds compared to patients without such characteristics. Fig. (2) depicts a summary of the key findings of our study.

4.2. Serum Urea And Prognosis

Serum urea, the terminal product of protein and amino acid metabolism and the major circulating pool of nitrogen, is produced exclusively in the hepatocytes in five reactions (two first steps in the mitochondrial matrix and the last 3 in the cytosol - Krebs-Henseleit urea cycle), and is excreted in the urine (about 80% of the eliminated waste nitrogen). Urea plays key roles in detoxification of harmful ammonia produced by amino acid catabolism and in osmoregulation [29]. Serum urea concentration is a cumulative result of multiple influences, including protein intake and catabolism, physical activity, fluid balance, liver synthetic function, urea recycling in the colon, tubular urea reabsorption, endocrine (especially, adrenal gluco- and mineralocorticoids) and renal neurohormonal activation [2, 3, 5, 9, 29-37]. Although the liver is the main ureagenic organ, and urea plays multiple roles in different homeostatic mechanisms, in clinical studies until now, urea is often interpreted as a biochemical marker of renal function and its relation with other liver-specific functions and protein/nitrogen metabolism remains largely neglected. It should, however, be realised that serum urea concentration is maintained through tight coordination of many metabolic pathways and reflects the complicated interrelations between nutritional and hydration status, protein metabolism, liver, renal, gut, muscle, cardiovascular and endocrine systems. Compared to creatinine and GFR, changes in urea levels are more dependent on neurohumoral mechanisms regulating the reabsorption process (renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and vasopressin) [3, 5, 9, 11, 36]. Elevated blood urea levels by inhibiting nitric oxide production may contribute to atherogenesis [38]. Increased urea should be considered not as mere biomarker of kidney damage, but an important factor in the multi-organ pathogenetic interactions. Abnormal urea, which may result from and be pathophysiologically linked to a wide variety of conditions, is prevalent in the elderly with multiple comorbidities, can lead to poor outcomes and, therefore, constitute a useful parameter for predicting hospital outcomes, especially mortality, in different medical and surgical settings [2-7, 9-11, 28, 39-46]. Our findings in HF patients are in keeping with these observations.

Renal dysfunction (using GFR or creatinine levels) has been widely [14, 16, 47, 48], though not universally [49, 50], accepted as a significant risk factor for post-HF mortality. Only few studies focussed on urea, and the published data have been conflicting. Elevated urea on admission has been reported as an independent predictor of in-hospital mortality [14] and included in some scoring models [17, 18, 51], but according to other studies urea was only marginally related [16] or not correlated with fatal short- and long-term outcome [15, 52].

In our study, urea level expressed both as a continuous and categorical variable demonstrated a significant association with poor outcomes in HF patients. Admission urea was the strongest correlate for hospital mortality and the second strongest for HPIR in comparison with all other tested biochemical parameters. Urea >7.5mmol/L and >10mmol/L performed best for predicting in-hospital death, and were associated with 2.6- and 3.7- fold (adjusted for age and gender) increased mortality, respectively, and with 2.2-fold higher incidence of HPIR compared to patients with normal admission urea. For fatal outcome urea level is a stronger contributor than any other biochemical or clinical variable at admission; it appears to be an integrative measure reflecting the most severe changes in the metabolism and, therefore, its quantification should not be ignored in predictive models.

Our work confirms the few previous reports that have shown that urea is associated with increased mortality in HF patients [14, 18] and numerous studies demonstrating such link in older adults with serious illnesses. Our results, however, are the first to demonstrate in HF patients an association between admission urea and HPIR, indicating that blood nitrogen homeostasis is an important regulator of susceptibility and response to inflammation/infection. Importantly, elevated admission urea had a strong effect on hospital mortality and HPIR independent of various clinically relevant covariates including preoperative history of MI, COPD, CKD, anaemia, low albumin, GGT/ALT>2.5, high creatinine, increased PTH, vitamin D deficiency, fracture type, medication used, age and gender, making our findings more special since this was not done in previous studies.

Serum urea, however, did not show an independent association with LOS; its significant univariate association with prolonged LOS appears to be secondary to pre-fracture socio-demographic and clinical conditions and postoperative complications; it would be more meaningful when admission urea used for predicting primarily hospital death and developing HPIR.

We have further extended previous findings by exploring the prognostic value of admission urea (>7.5mmol/L) and outcomes in HF patients with and without other well-established preoperative risk factors, which allows to separate the contribution of elevated urea and other abnormal characteristics on the risks of adverse outcome. Increased urea as a prognostic indicator interacted with other risk factors in an additive and multiplicative fashion (Fig. 2). The highest mortality risk was documented by combination of elevated urea with history of MI (OR 5.7), or hypoalbuminaemia (OR 5.0), or GGT/ALT>2.5 (OR 4.7), or hyperparathyroidism (OR 4.6), or CKD (OR 3.9). The highest risk of developing HPIR demonstrated patients in whom elevated urea was accompanied by COPD (OR 7.8), or anaemia (OR 4.6), or GGT/ALT>2.5 (OR 3.7), or creatinine>90µmol/L (OR3.5). Some of these factors operate synergistically and together markedly enhance the risk of fatal outcome or/and HPIR. Patients with both increased urea and HPIR had a 9.7-fold higher risk of hospital death. These observations highlight the complex nature of postoperative outcomes, demonstrating that alterations in protein/nitrogen homeostasis on admission (as assessed by elevated urea, hypoalbuminaemia, higher GGT/ALT ratio), history of CKD, MI, COPD, increased creatinine levels, anaemia, and hyperparathyroidism have a strong detrimental prognostic influence per se, whereas presence of two conditions (elevated urea plus any of the abovementioned) further significantly aggravates prognosis (by 1.5-2-fold on average).

Furthermore, closer examination revealed that most of the abovementioned laboratory and clinical variables previously recognised as risk factors for poor outcomes were not predictive in patients with normal admission urea. Although in the regression models (adjusted for age and gender) serum albumin, PTH, creatinine, GFR (both as a continuous and as a categorical variable), as well as history of MI, anaemia and COPD showed significant associations with increased risk of mortality and/or HPIR, our analyses demonstrated, for the first time, that this effects achieved statistical significance in patients with elevated admission urea but not in subjects with normal urea; this aspect has been masked to date. Indeed, in patients with normal urea at admission, only CKD was a significant risk factor for hospital death and HPIR, and anaemia (Hb<120g/L) indicated a risk of HPIR, whereas other studied factors lost their discriminative value; even developing a HPIR did not increased mortality risk, but elevated urea remained a significant predictor when most of the abovementioned parameters were normal (Table 4). These results emphasise that the prognostic performance of characteristics previously recognised as risk factors for poor hospital outcomes depends on urea status, therefore, their clinical interpretation should be in conjunction with urea level.

Why urea is associated with increased mortality and HPIR is not yet completely understood. Considering the many urea-related complex metabolic and pathophysiological pathways, including inflammation [53, 54], oxidative stress [53-57], and stress-induced hypermetabolic/catabolic response [58-60], elevated urea in HF (as in other) patients may be viewed as an integrative (but unspecific) outcome-relevant marker of severity of chronic and acute conditions and ageing; it mirrors the patient’s degree of physiological reserves/frailty and altered homeostasis [61, 62] explaining the high risks for adverse effects.

4.3. Predictive Value of Elevated Urea

In older HF patients, admission urea >10mmol/L as a single parameter has a reasonable ability to predict hospital death (AUC 0.7252, accuracy 73.3%), while the discriminative accuracy of other studied clinical and biochemical variables is relatively low. An integration of two characteristics (urea>7.5mmol/L plus one traditional risk factor) materially improves the prediction of mortality and HPIR, as evidenced by increases in AUCs (Table 5). Among combined parameters at admission highest AUC for prediction mortality yielded elevated urea (>7.5mmol/L) plus low albumin (AUC 0.7731) or GGT/ALT>2.5 (AUC 0.7698) and for prediction HPIR elevated urea plus anaemia (AUC 0.6928) or increased creatinine (AUC 0.6561) or GGT/ALT>2.5 (AUC 0.6418). Urea combined with other easily obtainable parameters at admission reached reasonable accuracy in identifying HF patients who are at risk of hospital mortality (sensitivity of 51-78%, NPV>95%) and HPIR (sensitivity 30-60%, NPV >90%). Elevated urea at admission is a strong independent predictor for hospital death, in particular among subjects who developed HPIR; these two conditions combined demonstrate the highest predictive value for unfavorable survival outcome (AUC 0.8176) with sensitivity of 62.5%, high specificity (87.5%) and high NPV (96.6%).

In the past decade a number of studies have aimed to identify clinical factors and/or biomarkers of poor outcome in HF patients. The available prediction tools [63-68] are complex (need of special rating scales and calculations), time consuming, some include subjective assessment or show significant lack of fit [18, 69], and are not widely used in clinical practice. The presented here approach is based on routinely collected objective data, simple, easy to use and has a fair precision rate.

4.4. Practical Implications / Therapeutic Considerations

Elevated urea at admission signifies the presence of a serious underlying condition(s) which may negatively impact survival and response to stressors (fracture, surgery, blood loss, infection, etc.), and, therefore, should be properly assessed and treated. Urea status may help to optimise risk stratification, to identify modifiable conditions and timely initiate individualized appropriate management. In patients even with mildly increased serum urea at admission, especially when it is accompanied by hypoalbuminaemia, GGT/ALT>2.5, hyperparathyroidism, renal impairment, history of MI, anaemia or COPD, poor outcome should be suspected and, if possible, prevented; more than 50% of hospital deaths are classified as “at least possibly preventable” [70]. The identified in this study comorbid conditions independently associated with elevated serum urea offer additional avenues for risk stratification and preventive strategies. By reducing negative effects of these comorbidities (prophylaxis of myocardial necrosis, optimising pharmacotherapy for COPD, correcting anaemia), preventing contrast-related kidney injury, inflammatory/infectious and opioid-induced complications, optimising perioperative intravenous fluid management, addressing malnutrition, use of probiotics (shown to decrease the serum urea concentrations in patients with CKD [71]) and rapid mobilization it may be possible to improve hospital outcomes.

5. LIMITATIONS AND STRENGTHS

The following limitations of this single-centre study should be noted. Firstly, its observational design does not allow a causal conclusion. Secondly, the causes of hospital death as well as the causes of HPIR were not classified. Thirdly, our results are based on a single measurement on hospital admission, and these may change and fluctuate. Fourthly, the majority of patients were Caucasian, therefore, the results might not be applicable for other ethnicities.

The strengths of our study include its relatively large sample size, measurements of urea in parallel to a variety of clinical and laboratory parameters, use of multivariate regression models to investigate the independent association of urea and comorbid conditions and outcomes, analyses of differential performance of previously established risk factors in patients with and without elevated serum urea at admission, and validation of the prognostic value of urea for hospital outcomes in an independent cohort. The variance inflation factor in all our regression models was ≤ 1.16, indicating that the amount of multicollinearity was not significant.

CONCLUSION

In older HF patients, serum urea, a routinely measured key factor of nitrogen homeostasis, was identified as an independent and valuable prognostic indicator for predicting poor hospital outcomes, in particular, mortality and developing HPIR. The predictive value of elevated urea was superior to other risk factors, most of which lost their discriminative ability when the admission urea levels were normal. The predictive performance of urea increased significantly when it was combined with other prognostic indicators. The risk of in-hospital death was almost 10 times higher in patients with elevated admission urea who developed HPIR.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| Ac | = Accuracy |

| Alb | = Serum albumin |

| ALP | = Alkaline phosphatase |

| ALT | = Alanine aminotransferase |

| AUC | = Area under receiver operating characteristic curve |

| CAD | = Coronary artery disease |

| CVA | = Cerebrovascular accident |

| CI | = Confidence interval |

| CKD | = Chronic kidney disease |

| COPD | = Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| CRP | = C-reactive protein |

| DM | = Diabetes mellitus type 2 |

| G/A | = Gamma-glutamyl transferase/alanine aminotransferase ratio |

| GGT | = Gamma-glutamyl transferase |

| GFR | = Glomerular filtration rate |

| Hb | = Haemoglobin |

| HF | = Hip fracture |

| HPIR | = High postoperative inflammatory response |

| LOS | = Length of hospital stay |

| MI | = Myocardial infarction |

| NPV | = Negative predictive value |

| OR | = Odds ratio |

| PPV | = Positive predictive value |

| PTH | = Parathyroid hormone |

| RCF | = Residential care facility (permanent) |

| 25(OH)D | = 25(OH) vitamin D |

| ROC | = Receiver-operating characteristic curves |

| Se | = Sensitivity |

| Sp | = Specificity |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

This study was approved by the Australian Capital Territory Health Human Research Ethical Committee and waived the requirement for written consent as only routinely collected and anonymized before analysis data were used.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No animals were used for studies that are the basis of this research.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Written consent as only routinely collected and anonymized before analysis data were used.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.