RESEARCH ARTICLE

Midterm Results of 58 Fractures of the Coronoid Process of the Ulna and their Concomitant Injuries

J Kiene*, 1, J Wäldchen1, A Paech1, Ch Jürgens2, A.P Schulz2

Article Information

Identifiers and Pagination:

Year: 2013Volume: 7

First Page: 86

Last Page: 93

Publisher ID: TOORTHJ-7-86

DOI: 10.2174/1874325001307010086

Article History:

Received Date: 12/9/2012Revision Received Date: 14/3/2013

Acceptance Date: 14/3/2013

Electronic publication date: 19/4/2013

Collection year: 2013

open-access license: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5/) which permits unrestrictive use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Background:

In general, fractures of the coronoid process are rare and usually occur in combination with additional elbow joint injuries. The treatment of these injuries aims to regain a stable as well as a flexible and loadable joint. Although there is currently little evidence, therapy recommendations remain controversial. Therefore, the aim of this study was to prognostically determine relevant factors for therapy recommendation by analysing a representative patient population of two trans-regional trauma centres.

Material and Methods:

Seventy-seven patients with a fracture of the coronoid process were treated within an 8-year period (2001 to 2009). After an average of 48 months (SD 31), treatment outcome of 58 patients (75%) was acquired. The results were statistically analysed.

Results:

The average age of the patient was 51.8 years (SD 13.6); 36 were male and 34 had a fracture on the right arm. Applying the fracture types of the coronoid process in accordance with Regan/Morrey, the result was: Type I (19), II (17) and III (22). Further injuries were also detected: 40 radial head fractures, 17 proximal ulnar fractures and 2 fractures of the olecranon. A luxation was detected in 44 of the 58 patients (76%). The patients’ average MEPS (Mayo Elbow Performance Score) was 80.6 points (SD 18), with significant differences between the various therapy strategies. Fifteen% of the coronoid process fractures were reconstructable to a limited extent only by means of osteosynthesis. In 33% of the patients, instabilities remained. The average extension/flexion came to 107° (SD 28), and pronation and supination 153° (SD 38).

Conclusion:

At present, a surgical therapy of ligamentary injuries cannot be statistically justified. A stable osseous reconstruction appears to make more sense. The strongest negative prognostic parameters in our patient population were: therapy with an external fixator, immobilisation for more than 21 days, the occurrence of complications and unstable osteosyntheses on the coronoid process.

INTRODUCTION

The coronoid process (PCU) is the most important osseous stabiliser of the elbow joint (EJ) [1]. Biomechanical studies have extensively shown that an isolated fracture involving over 50% of the PCU leads to an instability involving dorsal luxation of the joint, despite intact capsule ligaments [2, 3]. In combination with the loss of the radial head, a PCU-deficit of 25% is sufficient to allow for a dorsal reluxation [2]. The stabilisation of the joint against varus-valgus stress is primarily effected by the ulnar and radial collateral ligaments [1, 4]. Thus, a greater valgus instability can be expected in the case of an isolated transection of the ulnar ligament apparatus when compared to a sole radial head resection [5]. Hyperextension trauma [6] and hypersupination trauma during a twisting fall [7] will be discussed later as examples of an accident causing an elbow luxation.

Overall, fractures of the coronoid process are rare and appear as concomitant injuries in 2 to 11% of elbow luxations [8, 9]. This represents an incidence of 5.21 per 100,000 people a year [10]. Approximately 23 to 61% of coronoid fractures are treated with surgery [11, 12]. The typical injury combination of a PCU and radial head fracture along with an elbow luxation, which consequently causes joint instability, is referred to as the “terrible triad” injury of the elbow joint [13]. Clinical studies on therapies of various injury combinations and their different degrees of severity are difficult to carry out as the number of cases is low and therapies are sparsely standardised across hospitals. In two cooperating trans-regional trauma centres using the same therapy strategy, we performed a retrospective follow-up examination to identify medium-term treatment outcomes and isolate prognostically relevant factors.

MATERIALS AND METHODOLOGY

Seventy-seven patients with a fracture of the coronoid process were treated in an 8-year period (2001 to 2009). Within the scope of a retrospective study (ethics commission of the University of Lübeck, Ref No: 10-024), the treatment outcome of 58 patients was acquired. Ten of the 58 (17%) patients filled in the questionnaire only, while for 14 patients (24%), medical reports existed for submission to insurances and 34 patients (59%) took part in the actual follow-up examination. After an average of 48 months (SD 31; 9 to 120 months) and following initial treatment, the treatment outcome of 58 patients (75%) was obtained.

In accordance with the Mayo-Elbow-Performance-Score (MEPS) [8] and the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand Score (DASH) [14], subjective details regarding pain, joint stability and function in everyday life were recorded. During the clinical follow-up examination, circumference measurements and motion ranges of the arm’s joints were documented using a standardised measurement log (form F4222 [15]). The stability of the elbow joint was measured with a protractor in steps of 5 degrees via varus-valgus stress in the extended position and as a deviation of the longitudinal axis. Afterwards, force was measured in a 90° flexed position of the elbow joint, with the subject seated, using a Genius force measuring device (0 - 5 kN, FREI AG, Kirchzarten, Germany). The measurements were carried out three times per patient and the means recorded. Based on indication, an X-ray of the elbow joint was carried out (20 out of 48 patients).

The recorded data were saved in an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft) and anonymously analysed in cooperation with a statistician employing the SPSS statistics software (Version 19, IBM, Ehningen, Germany). The data underwent descriptive statistical analysis, including analysis of frequencies and distributions as well as an analysis of variance (ANOVA). The non-parametric group comparisons were conducted utilising the Mann-Whitney U-test. Pearson’s correlation analysis was used on data subjected to normal distribution. Mean numbers of groups were rounded to integers and significances to the third decimal place. The analysis was based on MEPS and DASH. According to Kendall, both rating scores strongly correlate (τb =-0,867, p=0,000); therefore, only one score (MEPS) was used for statistical analysis.

Significant differences or correlations between a specific pattern of injury or a specific treatment and the follow-up examination result were explored. Thus, individual injuries as well as recurring injury combinations were analysed (Table 1).

Patient Group Ratios of Re-Examined to Treated Patients and their Average Follow-Up Findings with Reference to Ulnohumeral Extension/Flexion, Lower Arm Rotation (Pronation/Supination), Average Instability Measured in ° During Varus-Valgus Stress and the Obtained MEPS (Rounded Values, No Significant Differences)

| Groups | Re-Examined/Treated Patients | Ulnohumeral Mobility | Lower Arm Rotation | Valgus | Varus | MEPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TT | 12/16 | 106° | 173° | 12° | 10° | 81 |

| ProxUlnTT | 15/16 | 92° | 124° | 5° | 6° | 78 |

| LuxPCU | 8/11 | 114° | 163° | 8° | 4° | 79 |

| MontPCU | 1/1 | 70° | 180° | 5° | 0° | 75 |

| IsoPCU-F | 3/4 | 115° | 142° | 3° | 3° | 71 |

| PCURH-F | 7/8 | 131° | 169° | 4° | 5° | 89 |

| OlePCU-F | 2/2 | 120° | 170° | 0° | 0° | 100 |

Key: TT = terrible triad, ProxUlnTT = proximal ulnar fracture with TT, LuxPCU = PCU fracture with luxation, IsoPCU-F = isolated PCU fracture without luxation, PCURH-F = PCU and radial head fracture without luxation. OlePCU-F = fracture of the olecranon with PCU-fracture without luxation, MontPCU = metaphysial ulna fracture with PCU-fracture and radial head luxation. ° = Degree, measured with a protractor.

RESULTS

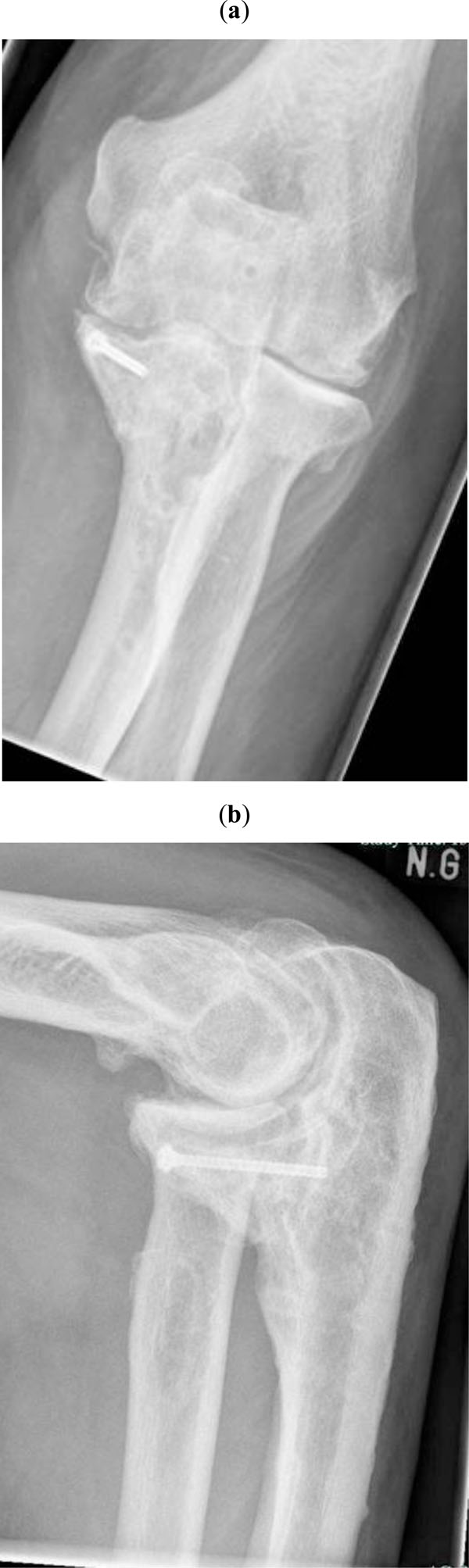

Injury Details

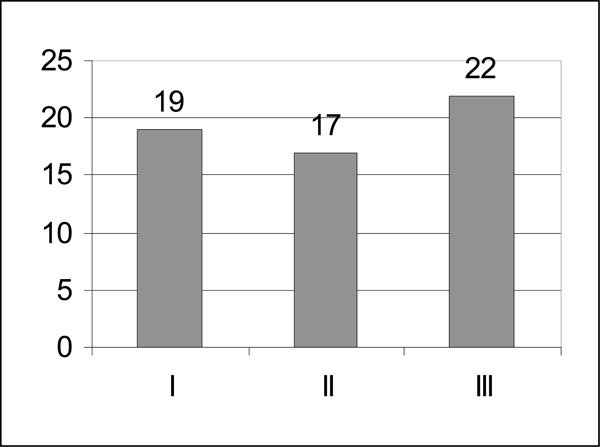

At the time of the accident, the average age was 51.8 years (SD 13.6; 15 to 79 years); 36 were male (62%) and 34 fractures were on the right elbow joint (59%). According to Regan/Morrey [12], the fracture type of the coronoid process was: Type I (19; 33%), II (17; 29%) and III (22; 38%) (Fig. 1).

|

Fig. (1). Distribution of the 58 coronoid fractures (using the classification of Regan/Morrey). |

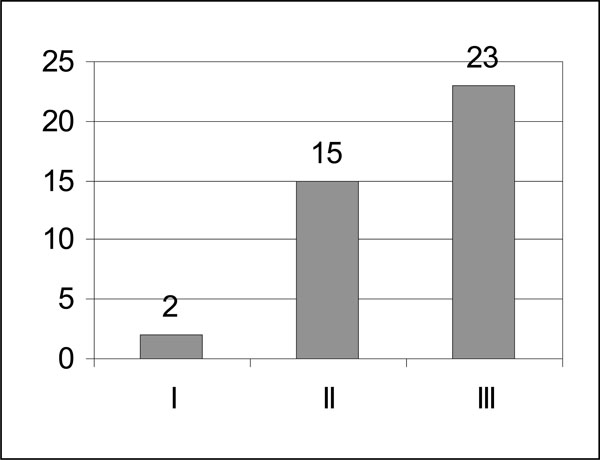

Forty radial head fractures were detected as additional individual injuries - classified according to Mason [16] as: Type I (2), II (15) and III (23) (Fig. 2). Five patients had an additional radial neck fracture. Furthermore, we found 17 proximal ulnar fractures; one of these was a metaphysial Monteggia fracture (Type 3 according to Bado) [17] and two were fractures of the olecranon. In 44 of the 58 patients (76%), a previous elbow joint luxation could be detected.

|

Fig. (2). Distribution of the 40 radial head fractures (using Mason’s classification). |

The following injury combinations were observed: 16 patients with a typical “terrible triad”-injury (TT), 16 with a terrible triad-injury and a proximal ulnar fracture (ProxUlnTT), 11 with luxation and an isolated PCU fracture (LuxPCU), one with a Monteggia fracture, a PCU fracture and a RH luxation (MontPCU), four isolated PCU fractures without luxation (IsoPCU-F), eight combinations of PCU and RH fractures without luxation (PCURH-F) and two fractures of the olecranon with a PCU fracture without luxation or involvement of the radial head (OlePCU-F) (Table 1).

Thirty-one of the 58 (53%) injuries were caused by low-energy traumas; 22 of these by a forward fall on level ground. Only 7 fractures (12%) were caused by high-energy traumas. Five post-traumatic nerve lesions were documented as well as three open bone fractures. Other observations included no injuries to vessels, 8 flake fractures of the humeral articular surface, one scaphoid fracture and four ipsilateral distal fractures of the radius.

Therapy Strategies

A total of 56 out of 58 patients (96%) underwent at least one surgical procedure; 42 of these had a maximum of 2 surgeries and 15 were operated on at least three times, including the removal of fixators (rated as a separate procedure). Two patients were treated conservatively only.

Thirty-three of the 58 PCU fractures (57%) were treated with surgery; 18 fractures were primarily reconstructed with the aid of screws, six with mini-plates, three with a lasso-sling and four using a coronoid substitute made from an autologous osteochondral block of a resected radial head. Two patients only had bone fragments removed (Table 2).

Primary Surgical Therapy of PCU Fractures

| Surgical Therapy | Number of Fractures Operated on |

|---|---|

| Screws | 18 |

| Mini plates | 6 |

| Lasso sling | 3 |

| Osseous replacement | 4 |

| Isolated fragment resection | 2 |

Regarding therapy, the indication was substantially influenced by the type of fracture. In line with this, only 2 of the 19 type-I fractures (11%), 12 of the 17 type-II fractures (71%) and all 22 type-III fractures (100%) underwent surgery (Table 3).

Proportion of PCU Fractures Treated with Surgery by the Type of Fracture [12]

| Type of Fracture According to Regan/Morrey | Number of Fractures | Fractures Operated on | Proportion of Operated Fractures in % |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | 19 | 2 | 11 |

| II | 17 | 12 | 71 |

| III | 22 | 22 | 100 |

RH fractures were also treated by the type of fracture. The two Mason I and two Mason II fractures were conservatively treated; the remaining 13 Mason II fractures and all 23 Mason III fractures were treated with surgery. Therefore, 9 RH fractures were primarily treated with screws only, 3 with Leibinger mini-plates, 20 primarily by complete RH resection and another 4 by partial RH resection. In the case of three redislocated screw osteosyntheses, RH resections were necessary secondarily: 2 to 3 weeks after primary surgery, three primarily resected RH were secondarily replaced with a bipolar RH prosthesis (model CRF II, Tornier, Burscheid, Germany), in line with Judet’s technique [18]. Hence, a total of 36 out of 40 RH fractures (90%) were treated with surgery (Table 4).

Surgical Therapy of Radial Head Fractures

| Surgical Technique | Number of Surgeries |

|---|---|

| Primary screws | 9 |

| Primary plate | 3 |

| Partial resection | 4 |

| Primary complete resection | 20 |

| Secondary radial head prosthesis | 3 |

In most cases, the 17 proximal ulnar fractures were stabilised with dorsally applied small fragment plates (conventional or fixed-angle), the 2 fractures of the olecranon were treated with a K-wire cerclage procedure.

In 18 of the 44 (41%) luxated joints, the ruptured collateral ligament apparatus was either re-fixed or stitched with surgery (14 times radial and 5 times ulnar).

Before heterotopic ossification, prophylactic measures were taken for all patients by the oral administration of 3x50mg Diclofenac for 2 weeks [19].

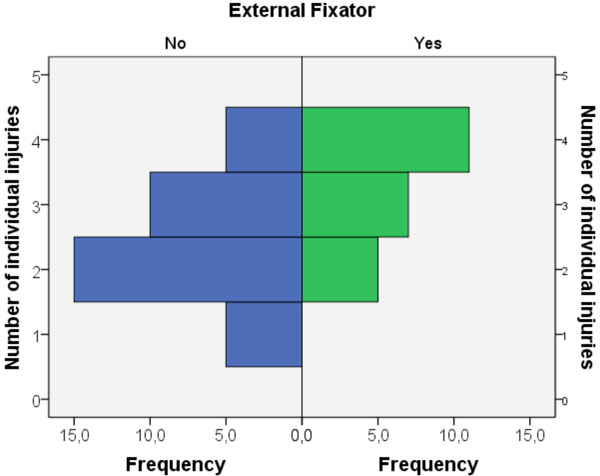

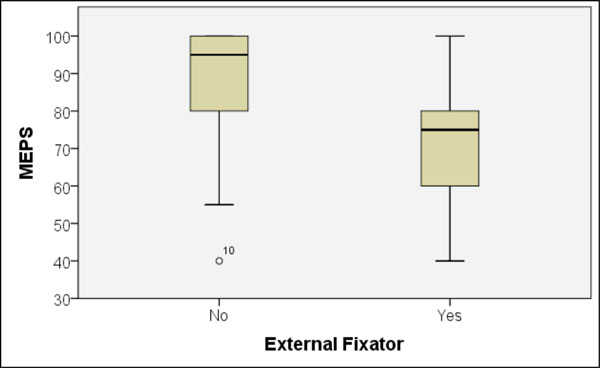

An elbow joint-bridging AO external fixator was primarily applied dorsally in 17 patients and secondarily in 6 patients over an average duration of 40 days. The other 35 patients had to wear postoperatively a cast on the upper arm for an average of 23 days. The number of cases of injured osseous and ligamentary structures per elbow joint came to an average of 3.26 in the fixator group and 2.43 in the group without fixator (p = 0.001, Mann-Whitney U-test). Hence, each fracture as well as the detected luxation was counted as an individual injury (Fig. 3). Fifteen out of 23 (65%) patients with an external fixator needed at least one revision surgery, whereas only 7 out of the 35 (20%) patients without an external fixator had to undergo a revision surgery (p = 0.000, Fisher's exact test). The total of all in-patient stays in the upper-arm cast group lasted an average of 18 days and in the fixator group, the stays amounted to 52 days (p = 0.000, Mann-Whitney U-test). The proportion of suture procedures or RH resections did not differ significantly between the two groups; the duration of continued outpatient physiotherapy did not differ either.

|

Fig. (3). Significantly higher number of individual injuries per elbow joint in the fixator group (p = 0.001, Mann-Whitney U-test). |

Ten partial or complete nerve lesions were noted in particular as postoperative complications. The following were indications for additional surgeries: one compartment treatment on the lower arm, three joint mice, two pseudarthroses of the ulna, 4 restricted movements (once with heterotopic ossifications) and 2 failures with osteosynthesis. One patient who suffered persistent luxations in spite of a PCU reconstruction with an iliac bone graft and a previous RH resection received a complete elbow joint prosthesis (Biomet IBP, Berlin, Germany).

Follow-Up Examination Results

Ten out of the 58 (17%) patients completed the questionnaire only (overall, 46 patients completed it). In the case of 14 patients (24%), there were medical estimates available for submission to an insurance company and 34 patients (59%) took part in the actual follow-up examination. An average of 48 months (SD 31, 9 to 120 months) after initial treatment, 58 out of the 77 patients’ treatment outcomes (75%) could be ascertained; the remaining 19 patients (25%) could no longer be approached.

The statistical evaluation of the data results in a normal distribution of coronoid fractures by age and arm side was performed.

Twenty-three patients indicated to be free of pain, 17 said they had slight pain, 14 stated to have moderate pain and 4 patients had intense pain depending on the load.

Fifty of the 58 patients stated that they had no relevant limited functionality during their daily activities.

Forty (69%) patients subjectively said they had a stable joint. However, an objective stability check resulted in an increased lateral folding of over 10° in 21% of those patients. Eighteen (31%) patients indicated a moderate to strong feeling of instability; 58% of those objectively had an increased mediolateral folding. At the time of follow-up, a reluxation could not be detected in any patient.

The clinical follow-up examination revealed a persistent extension deficit of an average of 19°; flexion was actively possible up to an average of 126° (overall 107° ulnohumeral; SD 28, 5° to 155°). Pronation came to an average of 82° and supination to 71° (total rotation 153°; SD 38, 0° to 180°).

The force measurements revealed no significant differences. On the injured arm, the force measurements averaged 91 N on the left arm and 96 N on the right; the healthy left arm displayed 93 N and the healthy right one 92 N. The men’s force values resulted in an average of 99 N for both left and right arms, while those for the women were 83 to 85 N (not significant).

A neurological deficit remained in 3 of the 5 post-traumatic nerve lesions, as well as in 3 out of the 10 nerve lesions caused by surgery.

On average, the MEPS amounted to 80.6 points (SD 18, 40 to 100). Therefore, 21 patients had an excellent result (≥ 90), 20 showed good results (≥ 75), 10 patients came up with fair (> 60) (e.g. Fig. 5) and another 7 with poor results (< 60) (Fig. 4).

|

Fig. (4). Number of patients according to their MEPS values (absolute numbers). |

On average, 52 points (SD 25; 30 to 122) were achieved for the DASH scores. For further analysis, only one score (MEPS) was taken into account as both scores correlate strongly to each other (τb = - 0.867, p = 0.000), according to Kendall.

Statistical Analysis

The relevant results of the descriptive statistics as well as of the analysis of variance are already quoted in the corresponding paragraphs.

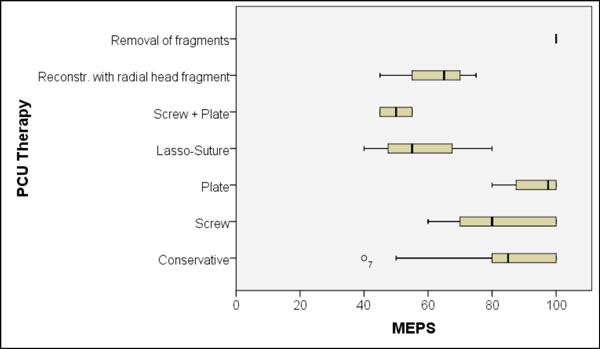

Regarding the MEPS, statistical analysis revealed no significant differences between the individual PCU fracture types. However, Pearson’s analysis demonstrated that the occurrence of complications correlated positively and significantly with the type of fracture (r = 0.263; p = 0.046). The surgical therapy strategies also differed significantly with respect to their results (Fig. 6). Patients whose PCU fractures could be stabilised by either conservative treatment or by just one method of osteosynthesis (screws or plates) achieved significantly better results than those 9 patients (15%) treated with lasso-slings, with a screw-plate-combination or with a replacement using an osteochondral block (p = 0.005 to 0.015; Fisher's LSD test).

|

Fig. (6). Significant differences in the achieved MEPS between the different therapy-strategies for the coronoid (p = 0.005 to 0.015; Fisher's LSD test). |

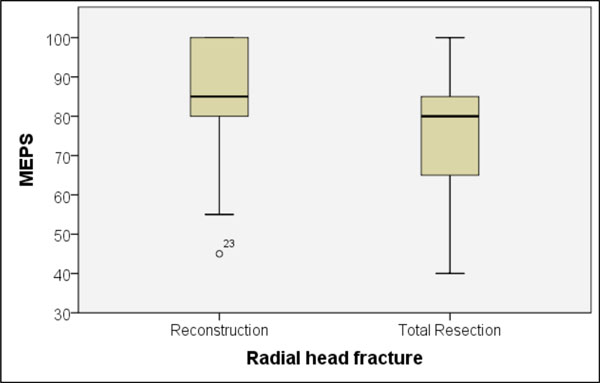

Regarding RH fractures, the results were similar - there was also no significant difference in relation to the Mason classification. However, tendential differences were revealed between patients with preserved RH and those, whose RH was resected (Fig. 7).

|

Fig. (7). Tendential difference in MEPS values in cases of either preservation or loss of the fractured radial head (p = 0.139; Mann-Whitney U-test). |

Patients who were dependent on an external fixator during their therapy achieved a significantly worse MEPS value and joint mobility than those without the fixator (Fig. 8). Patients without the fixator achieved a mean MEPS of 86 points, while those with a fixator had an average of 73 points (p = 0.001, U-test). The average extension/flexion mobility was 119° without the fixator, and 90° (p = 0.000, t-test) with it. Rotation of the lower arm in pronation and supination was 162° without fixator therapy, and 141° (p = 0.037, U-test) with it. Between the two groups, the objectively measured varus-valgus stability revealed no differences.

|

Fig. (8). Significant MEPS differences between patients with or without the external fixator application (p = 0.001, Mann-Whitney U-test). |

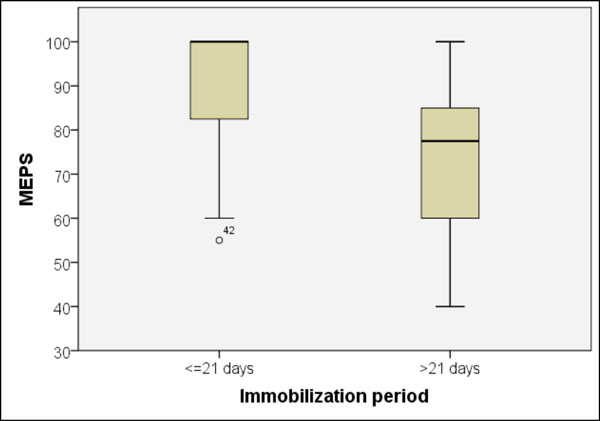

There were also significant MEPS differences between patients who were immobilised for a maximal 21 days or for more than 21 days (p = 0.000, U-test) (Fig. 9). Therefore, patients achieved average MEPS of 91 and 74 points and a range of motion in the extension/flexion of 127° and 96°, respectively. Differences regarding patterns of injury or surgical therapies between the two patient groups could not be verified.

|

Fig. (9). Significant MEPS difference (p = 0.000, Mann-Whitney U-test) in patients with cast immobilisation for ≤ or > 21 days. |

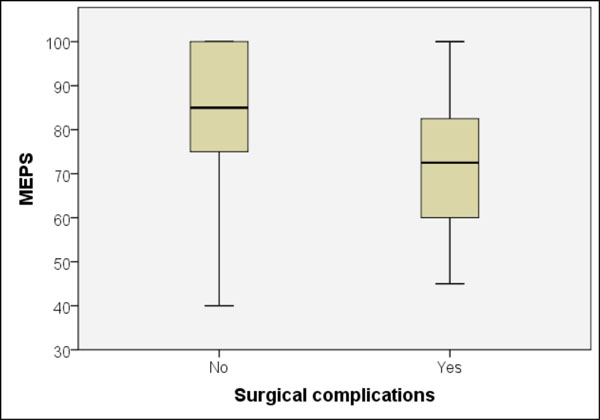

The occurrence of local complications such as reluxations or nerve lesions during treatment revealed significant MEPS differences (p = 0.011, U-test) (Fig. 10). Patients without complications achieved an average of 85 points and those with at least one complication 70 points.

|

Fig. (10). Significant MEPS difference between patients with and without complications during treatment (p = 0.011, Mann-Whitney U-test). |

Eighteen of the 44 luxations (41%) were treated with stitches on the ligament apparatus. Seventeen out of 26 patients with no stitches (65%) subjectively indicated that they had a stable feeling in the joint in spite of a previous luxation; the same applied to 12 out of the 18 patients (67%) with stitches. Regarding MEPS or ulnohumeral mobility, the clinical follow-up examination demonstrated no difference between surgically- or conservatively-treated luxations.

The MEPS between the male and female patients showed no difference; the difference between patients aged under or over 40 at the time of the accident was also not significant. A difference between the two trauma centres could not be verified.

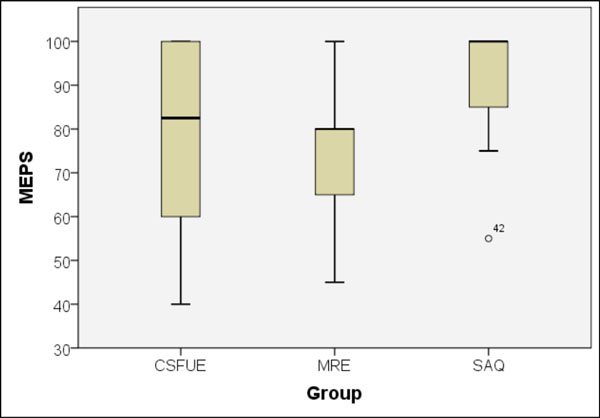

The results were also compared by the type of data collection, i.e., study-related data, advisory examination or questionnaire only. Questionnaire results (10 patients, mean MEPS was 91 points) were better than those from the advisory (14 patients, mean MEPS was 76 points, p = 0.044) or study-related examinations (34 patients, mean MEPS was 80 points, p = 0.081). The results of the advisory medical reports and the study-related follow-up examination did not differ statistically (p = 0.50) (Fig. 11).

|

Fig. (11). MEPS differences between study-related examination (CSFUE), advisory medical report (MRE) and questionnaire results (SAQ). |

Furthermore, the analysis revealed moderate significant correlation ranges between the statements regarding remaining pain and objectively (r = 0.512, p = 0.001) or subjectively (r = 0.605, p = 0.000) existing instability of the elbow joint.

DISCUSSION

On the whole, there are a small number of retrospective studies dealing with the clinical course of coronoid fractures [11, 20-25]. Only one study features over 40 cases [11]. They all report on injury combinations and show that therapeutic strategies have become more surgical recently than 20 years ago [12]. The reason, besides the rather unsatisfactory results after predominantly conservative therapy [12], is the sophisticated knowledge of the biomechanical implication of the coronoid process [2, 3, 5]. The poorly treatable instability of injury combinations involving PCU with RH fracture and collateral ligament ruptures (terrible triad) continues to be a therapeutic challenge [25].

The proportion of concomitant elbow joint luxations in PCU fractures has not been determined to date. In 44 out of 58 patients (76%), we noticed a luxation. Adams et al. [11] registered a luxation in only 49 out of 103 (47%) coronoid fractures in their patient population and Regan in just 12 out of 35 patients (34%) [12]. We could not verify a significant difference in the outcome regarding patients with or without luxation. The follow-up results showed preference for neither surgical nor conservative therapy of ligament injuries. The most recent publications [21, 22, 24, 26] reported on surgical reconstructions of the collateral ligament apparatus in luxation fractures, but not using any prospective studies. The only available prospective study on isolated ligament lacerations without osseous instability is [27], which shows that the follow-up results of surgical procedures are not better than those of conservative therapies.

During follow-up, the coronoid process fractures treated by us revealed - in relation to the MEPS - no significant differences between the types of fracture. Significant differences in the functional result were described by Regan and Morrey [12], where the therapy was, to a certain extent, stage-independent and predominantly conservative. Adams et al. also described an increasing restriction of ulnohumeral mobility in relation to the coronoid fracture type, where the evaluation was complicated by a rising number of additional fractures [11]. A primarily stable osteosynthesis of the PCU fracture appears to be important for a successful surgical procedure [21]. However, this has its limits in cases of reduced bone quality caused by osteoporosis (9 of the 58 patients (15%) were aged over 65 at the time of surgery) and in multi-fragment fractures with osteosynthesis plates already in place. That is why the fractured coronoid process could not be preserved in 4 cases, but had to be replaced with an autologous bone block. In fact, one of those patients needed a complete elbow prosthesis due to a persistent reluxation. In the examined population, patients with combined variations of osteosyntheses (plate and screws) showed significantly poorer results than those treated with only one type of osteosynthesis (plate or screws). A total of 15% of the coronoid fractures could not be sufficiently treated and stabilised with the implants in place. Future studies should evaluate whether a more stable treatment can be achieved by using anatomically preformed fixed-angle plates (e.g., tifix-coronoid-plate, Litos, Ahrensburg, Germany). Moreover, in selected cases, stabilisation can be achieved by a coronoid substitute prosthesis [28].

The presence of an additional RH fracture is described as the biggest negative prognostic factor by Adams et al. [11]. In isolated occurrences of RH fractures, positive long-term results are mostly expected despite complete resections [29], even if the missing radial bracing on the Capitulum humeri leads to an additional load of the medial collateral ligament apparatus and the humeroulnar articular surface. Data regarding impacts on wrists are inconsistent [30, 31]. In luxation fractures of the elbow joint, there is a risk of persistent instability and reluxation after RH resection [22]. From a therapeutic perspective, maintenance or replacement therapies of the RH are being increasingly mentioned in more recent studies [11, 24, 32], even if some studies do report positive long-term results after complete RH resections in spite of a previous luxation [33, 34]. In the examined patient population, MEPS results for patients whose RH were preserved were only tendentially better than those with a complete resection. Therefore, we cannot statistically back up a therapy recommendation. However, having interpreted our data, we think it is biomechanically sensible to either preserve or replace the RH in order to achieve a better stability of the joint. Functional results also seem to support that in the long-term course [22, 24, 35].

In both trauma centres, follow-up care aimed to attain early mobilisation of the elbow joint at all levels, given that it has been demonstrated that a remaining flexion deficit prognostically correlates with the duration of immobilisation [36]. Thus, an immobilisation period of less than 3 weeks allowed for predominantly good to excellent results [22]. In the population we examined, significant differences in the outcome were also found between patients with a cast immobilisation period of less than 3 weeks and those of more, although both patient groups showed no differences in the type or number of injuries. Therefore, we regard immobilisation as an independent influencing factor. In contrast, a comparison of patients with or without application of an external fixator showed significant differences in the injury rate per elbow joint and in the rate of required revision surgeries. Hence, the significant differences can only partially be assigned to the immobilisation by the fixator. A prospective randomised study should initially clarify [37] whether a fixator with motion capacity can yield an advantage.

A total of 69% of the interviewed patients subjectively stated that they had a stable joint; 67% of the re-examined patients were, in fact, objectively stable. With that said, the proportion of stably-healed elbow joints was smaller than those in other follow-up examinations [21, 33, 38, 39]. However, the comparability is limited by different patient groups and missing data on clinical stability checks. Statistically, we were unable to determine a correlation between specific osseous or ligament injury combinations and therapeutic strategies. The remaining instabilities after completed treatment did not lead to recurrent luxations in our patient population, but based on the significant correlation between the pain statements and the associated load reduction, they have to be rated as substantial limited functionalities. In the long term, a limited joint stability also seems to exacerbate arthrosis [25]. Hall et al. reported on the link between pain and instability [40] and Adams et al. [11] described the connection between previous ligament injury and chronic pain. Therefore, achievement of a stable joint should not only be assessed by the reluxation rate, but also via the regained load-carrying ability.

Limitations of this study include the retrospective study design and in homogenous patient population, CT data was not available in all cases. Strength is the large follow up period monitored and the number of cases overseen by this study.

CONCLUSIONS

At present, fractures of the coronoid process can only be limitedly reconstructed by osteosynthesis and often heal with permanent functional deficits, their prognoses largely contingent on concomitant injuries. Remaining instabilities of the elbow joint appear relatively often after complex luxation fractures; instabilities are therapeutically difficult to manage and significantly correlate with pain. Surgical therapy of ligament injuries cannot be justified statistically. A stable osseous reconstruction appears to make more sense.

Predictive statements regarding individual injuries are, for fracture-specific therapy and simultaneous injury combinations, only just possible. The strongest negative prognostic parameters in our patient population were: therapy with an external fixator, immobilisation for more than 21 days, the occurrence of complications and unstable osteosyntheses on the coronoid process.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No financial assistance has been accepted for the conduction of this clinical study and its analysis. The aforementioned tifix-coronoid-plate from Litos was developed in cooperation with the lead author.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dr. Friedrich Pahlke for his comprehensive statistical analysis and also the staff of the participating hospitals for their active support.