RESEARCH ARTICLE

Knowledge Translation Tools are Emerging to Move Neck Pain Research into Practice

Joy C. MacDermid*, 1, Jordan Miller2, Anita R. Gross2

Article Information

Identifiers and Pagination:

Year: 2013Volume: 7

Issue: Suppl 4

First Page: 582

Last Page: 593

Publisher ID: TOORTHJ-7-582

DOI: 10.2174/1874325001307010582

Article History:

Received Date: 24/7/2013Revision Received Date: 23/8/2013

Acceptance Date: 23/8/2013

Electronic publication date: 20 /9/2013

Collection year: 2013

open-access license: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5/) which permits unrestrictive use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Development or synthesis of the best clinical research is in itself insufficient to change practice. Knowledge translation (KT) is an emerging field focused on moving knowledge into practice, which is a non-linear, dynamic process that involves knowledge synthesis, transfer, adoption, implementation, and sustained use. Successful implementation requires using KT strategies based on theory, evidence, and best practice, including tools and processes that engage knowledge developers and knowledge users. Tools can provide instrumental help in implementing evidence. A variety of theoretical frameworks underlie KT and provide guidance on how tools should be developed or implemented. A taxonomy that outlines different purposes for engaging in KT and target audiences can also be useful in developing or implementing tools. Theoretical frameworks that underlie KT typically take different perspectives on KT with differential focus on the characteristics of the knowledge, knowledge users, context/environment, or the cognitive and social processes that are involved in change. Knowledge users include consumers, clinicians, and policymakers. A variety of KT tools have supporting evidence, including: clinical practice guidelines, patient decision aids, and evidence summaries or toolkits. Exemplars are provided of two KT tools to implement best practice in management of neck pain—a clinician implementation guide (toolkit) and a patient decision aid. KT frameworks, taxonomies, clinical expertise, and evidence must be integrated to develop clinical tools that implement best evidence in the management of neck pain.

INTRODUCTION

Evidence-based practice [1, 2] is conducted through five steps: defining a clinical question, finding the evidence that addresses that issue, determining the quality of evidence, making an evidence-based decision by calibrating the best evidence with patient values and clinical experience, and evaluating the outcomes. It has been assumed that once the evidence is available it can be implemented, but the five steps of evidence-based practice do not explicitly address how to implement new clinical practices. Knowledge translation (KT) deals with the complex process where once the best evidence is identified, it must be moved into practice [3]. When knowledge is available but is not used, we can say there is a gap between knowledge and action. The purposes of this paper is to review issues relevant to moving neck pain evidence into practice by considering: the gap between knowledge and action, the theoretical underpinnings that can be used to develop new KT tools or interventions, and evidence supporting specific KT tools. We provide a taxonomy of KT interventions that can be used to classify existing tools or develop a KT strategy, and highlight examples of KT tools that can be used to implement neck pain evidence into practice.

THE KNOWLEDGE TO ACTION GAP

Gaps between knowledge and action can be costly to individuals and healthcare systems, particularly when the burden of the condition is high and outcomes are suboptimal. There is substantial evidence to indicate that this is the case for neck pain. Neck pain is a common condition as indicated by epidemiological studies that indicate a high incidence, an episodic nature, and overall high prevalence at the population level [4-7]. However, a subset of patients with neck pain develops chronic pain and disablement that becomes more resistant to interventions [8-10]. It has been estimated that amongst workers with neck pain, 14% experience multiple episodes of work absenteeism—these workers accrue 40% of all lost-time days [11]. Since the majority of new cases of neck pain can be managed with a stay active approach, and a substantial minority are at risk of transitioning into adverse outcomes, it is essential that appropriate management include selection and timing. While systematic reviews and overviews published in this special issue indicate a wealth of evidence [12-16], that information is imperfect and poorly implemented. Neck pain interventions typically demonstrate small to modest effects, with neck pain successfully rehabilitated in comparison to other orthopedic disorders [17].

A population-based survey conducted in 1995 suggested that 25% of those with neck and back pain seek the help of a healthcare practitioner [18]. Inefficient service utilization is suggested by the fact that people saw a mean of 5.21 provider types and had a mean of 21 visits. A variety of treatments were utilized, including some interventions where evidence is not supportive: electrotherapy (30%), corsets or braces (21%), massage (28%), ultrasound (27%), heat (57%), and cold (47%). The study suggested that there is overutilization of diagnostic testing, narcotics, and modalities, and underutilization of therapeutic exercise [19]. This finding was supported by a study evaluating exercise prescription for 684 patients with neck or back pain. Although the strongest evidence supports the use of exercise for these conditions, only 48% of the patients with neck pain were prescribed exercise [20]. Our practice surveys also indicate a substantial knowledge to action gap because physicians, physical therapists, and chiropractors who treat neck pain show substantial variations in practice both within and across disciplines [19, 20].

Inadequate management of neck pain is inconsistent with the availability of evidence. The Cervical Overview Group (COG) has observed the rapid increase in availability of randomized controlled trial (RCT) evidence over the course of their systematic reviews, having retrieved 24 RCTs in 1996; 88 by 2006; and 351 by 2011. This is further highlighted by our overview methods paper where we identified 202 systematic reviews and 57 clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) that form the evidence informing management of neck pain [21]. Although this evidence is positive as it provides foundations for evidence-based practice, it also presents substantial barrier to clinicians who find it difficult to keep up with a large volume of new evidence.

Implementing best practice is not a new concern, but the science of how we conduct it is now more recognized as a discipline onto itself. More than 100 terms and definitions have been identified to describe this concept [22]. Organizations that fund health research are acutely aware of the need to ensure that their investments in knowledge creation demonstrate benefit and have defined KT as: a dynamic and iterative process that includes synthesis, dissemination, exchange, and ethically sound application of knowledge to improve the health…, provide more effective health services and products and strengthen the health care system (Canadian Institutes of Health Research; http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/29418.html).

The complexities of KT have engendered general acceptance of the need for strong theoretical frameworks. Frameworks provide the essential structure by which we organize our understanding of complex issues. Frameworks can provide direction on starting a process, issues that need to be considered as essential to the process, assist with selection of strategies, or provide a means of communication about goals and outcomes. When developing or implementing tools, it is important to have a framework as a means of promoting better quality tool development, directional strategies for implementation, and a structure upon which to evaluate outcomes.

OVERVIEW OF PROMINENT KT FRAMEWORKS

KT is an emerging complex field supported by the use of conceptual frameworks. Different frameworks view KT through a specific lens and have variable focus on characteristics of the intervention, the context, the target audience, or the cognitive-behavioral components of behavior change. The Knowledge To Action (KTA) cycle is a framework that describes the research enterprise and research implementation process and allows one to identify where within that process one is situated. Typically, frameworks that focus on specific conceptual approaches or elements of KT are used to refine how one accomplishes the needed activities at that point in the cycle. People engaged in tool development need to understand the KTA cycle so they plan where they need to act. However, there is also a need for a theoretical framework that could assist with tool development or implementation. For example, it has been demonstrated that the use of theory can facilitate uptake of CPGs [23]. Hence, we review the most prominent frameworks.

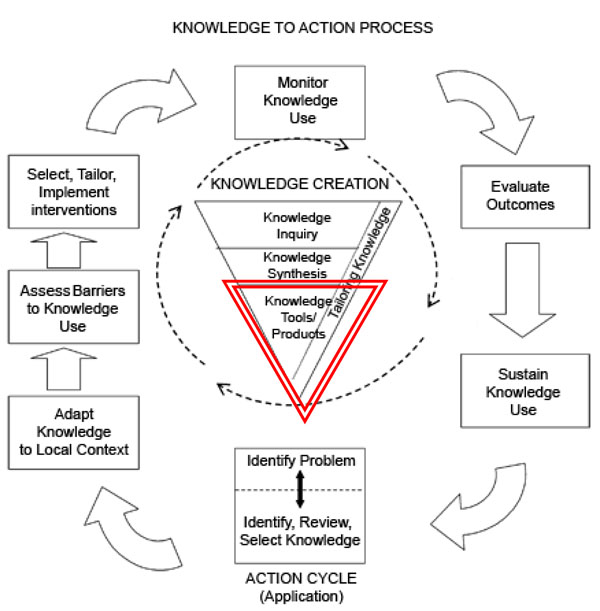

The Knowledge To Action Cycle (Fig. 1) is composed of an inner knowledge creation funnel that describes how individual research studies are funneled into “best evidence”. These synthesis activities can lead to evidence-based tools. The outer action cycle addresses the application/implementation of this best evidence. The implementation stage focuses on making knowledge useable for different users and contexts. This requires adapting the knowledge, identifying and addressing local or system barriers, and facilitating changes in practice that can be sustained over time. As new knowledge is implemented, it is common for new questions to arise. When researchers and knowledge users collaborate effectively, this contributes to the generation of the next wave of research.

In the KTA cycle, tool development occurs at the end of the knowledge creation funnel and is a transition into implementation. A KT tool is an intervention in a form of a tangible product or resource that can be used to implement best evidence into practice. Tools include CPGs, patient decision aids, devices/aids, and many other innovations that target different end users. The development of evidence-based tools is an emerging area of innovation that has the potential to enhance evidence-based practice, since tools can simplify the process of applying new research findings.

Systematic reviews and overviews/reviews of reviews are knowledge synthesis products that can bring together a large volume of clinical research into a more digestible format for clinicians. However, their terminal endpoint is typically recommendations. Clinicians find too many evidence syntheses have recommendations lacking description of the specifics of the intervention itself and, thus, are not directly implementable [24-26].

Our scoping review on the use of theory in KT identified three core KT frameworks that take on different perspectives including 1) Theory of Diffusion of Innovation; 2) Theory of Planned Behaviour; 3) Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services [33]. Theory was used most commonly to identify a potential predictor or mediator of KT. Less common uses were as a general philosophical framework to guide development of a KT educational strategy, to provide a framework for qualitative interview/analysis, or to identify outcome measures. These three models are highlighted below because they demonstrate that KT models often take the process of applying and using research evidence from different perspectives. We have highlighted models that focus on the innovation and type of end user, the cognitive processes of the user, and the environmental context in which best practices need to be used.

THE THEORY OF DIFFUSION OF INNOVATION

The Diffusion of Innovations (DOI) theory focuses on characteristics of the innovation and the target audience, as well as the process of implementation. It is arguably the oldest and most consistently cited “KT theory”, as it was developed in the 1950s to explain the spread of new ideas [29]. The theory relies on a sociological perspective where innovation is communicated “through particular channels, over time, among the members of the social system” [29]. Under this theory, innovations pass through specific stages of decision/adoption: awareness/knowledge, interest/persuasion, eval-uation/ decision, trial/implementation, and adoption/confirmation. Evidence-based tools can be considered innovations and implementation can be considered within this framework (Table 1). This theory defines important characteristics about tools that can affect uptake.

Characteristics of Innovations that Apply to Tool Development

| Characteristic | Definition | Implication for Tool Development for Evidence-Based Management of Neck Pain |

|---|---|---|

| Relative advantage | The degree to which the innovation is better than the current accepted standard practice. | KT tools/interventions have to be demonstrably better than current approach. Advantage can include more efficient practice (less use of time and resources) or better outcomes (less residual pain and disability). |

| Compatibility | The extent to which the innovation is consistent with existing values, past experiences and needs. | Neck pain KT tools/interventions must fit into the practice patterns of clinicians or be aligned with patients values. Professional beliefs may affect uptake and should be considered in tool design. |

| Complexity | The difficulty in understanding and using the innovation. | New KT tools/interventions should provide clear direction on what specific actions are to be implemented, and simplify the implementation process. |

| Trialability | The extent to which the intervention can be experimented with on a limited basis. | Tools/interventions should be readily accessible for use, and it should be evident how to use. Try out the tools of a small-scale before proceeding to full implementation. |

| Observability | The extent to which a visible result occurs. | KT tools/interventions should indicate how to measure outcomes using indicators that can show meaningful change has happened. |

The DOI theory also identifies different adopter categories (Table 2). We expect orthopedic surgeons, other health professionals, and patients to populate all of the different adopter categories. Thus, uptake of best practice will be variable and does require sustained efforts. Interventions to change behavior may need different strategies for each adopter group. For the early majority who are motivated to adopt change, they may respond to simple communication strategies that provide a rationale and supporting evidence. For the late majority who are cautious about change, more require substantive efforts may be needed, including personal contact and data demonstrating that others have achieved more positive outcomes through change.

Types of Knowledge Users Defined by Diffusion of Innovation

| Category | Identified Characteristics | Relevance for Tool Development/Uptake |

|---|---|---|

| Innovators | Daring, risky, sufficient control of financial resources to absorb possible loss, able to understand and apply complex technical knowledge, able to cope with uncertainty. | Likely to adopt technological tools, may adopt new tools without clear evidence they advance practice. |

| Early Adopters | Integrated in a social system, usually hold the greatest degree of opinion leadership, frequently serve as role models, respected by peers, successful. | Early users of new tools, may influence uptake for the early majority. |

| Early Majority | Frequently interact with peers, seldom hold positions of opinion leadership, usually the largest component of the system, deliberate before adopting new ideas. | Probable users of useful tools. Will need rationale and possibly evidence of effectiveness/utility. |

| Late Majority | Usually one third of target audience, reacts to pressure from peers, motivated by economic necessity, skeptical, cautious. | Unlikely to use new tools unless there is targeted intervention to push the change and evidence of clear benefit. Will follow the lead of the early majority. |

| Laggards | Not opinion leaders, usually more isolated, suspicious of innovation, tend to focus on the past, require long decision processes, may have limited resources. | Unlikely tool users despite substantial investment in promoting uptake. |

THE THEORY OF PLANNED BEHAVIOR (ToPB)

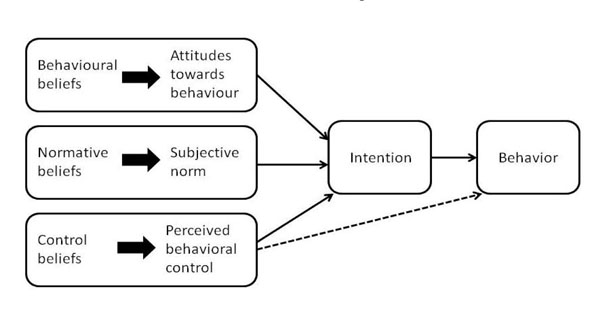

The theory of planned behavior (ToPB) [30, 31] was the most commonly used framework in our scoping review [32]. This framework assumes that cognitive processes that determine our intention are what drive behavior. Behavioral intentions are assumed to arise as a function of attitudes or beliefs about that specific behavior, the subjective norms (professional, cultural, and expectations) that relate to the performance of that behavior, and the individual’s perception of his/her ability to perform or change the behavior (Fig. 2). This framework has led to the development of tools that assess aspects of the individual’s beliefs and intention. This knowledge can then be used to design KT interventions and tools that target cognitive processes affecting behavior. A guidebook has been developed to create questionnaires that measure beliefs and attitudes as behavior determinants (http://www.rebeqi.org/ViewFile.aspx?i temID=212). Our scoping review indicates that the predominant use of the ToPB was in identifying potential predictors or mediators of KT [32]. The ToPB does not directly address tools or interventions since it focuses on intention to adopt specific behaviors. However, the cognitive factors limiting uptake can be intervention targets. For example, investigating clinicians’ views on an evidence-based web or mobile device application (‘app’) for patients to invoke self-management of their neck pain might be more effective if clinicians believe that technological innovations are usually positive (behavioral beliefs), that their college approves their use (normative beliefs), and that they are allowed to use them in their clinical setting (control beliefs). In contrast, some clinicians would have different beliefs such as that technology depersonalizes and compromises their approach to patient-centered care. In this case, unless tools are structured and implemented with an emphasis on how the tool can work in conjunction with a patient-centered approach, uptake would be compromised.

|

Fig. (2). Theory of planned behavior (reference: Azjen,1991 [30, 31]). |

PROMOTING ACTION ON RESEARCH IMPLEMENTATION IN HEALTH SERVICES FRAMEWORK

A framework for Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARIHS) was developed in nursing and is the most commonly used framework in nursing KT [32]. Successful research implementation is considered to be a function of the relationships amongst the evidence, context, and facilitation. Successful implementation is more likely if research evidence is clear and of high quality. Different types of evidence are recognized as being influential, including research evidence, clinical experiences, patient experiences, and local data/information. In fact, where these pieces of evidence are used in isolation, KT may be compromised. Context is an important feature of this framework, which recognizes that the setting in which change happens plays a central role in implementation. Contextual factors that promote successful implementation are categorized under three broad themes of culture, leadership, and evaluation. “Learning” organizations that pay attention to individuals, group processes, and organizational systems are considered optimal. Transformative leadership and ongoing evaluation with feedback are valued elements. The framework acknowledges the importance of facilitation to changing clinical practice. Facilitation is characterized by its purpose, role, and the skills/attributes required of the facilitator.

This framework also does not specifically promote the need for tools but implicitly recognizes their importance, as a number of generic KT tools have been developed to assist with implementation based on this theory. A revised version of the model with accompanying tools for implementation can serve as a guide for KT (http://www.implementationscience.com/ content/6/1/99/table/T4).

When developing or implementing tools, it is wise to choose a framework that is salient to the challenges being faced, is able to help explain the problem and develop solutions, and is supported by evidence that the framework has been useful in similar contexts.

UNDERSTANDING THE SPECTRUM OF KT TOOLS USING A TAXONOMY

KT interventions are diverse and can include a variety of processes that are familiar in healthcare settings or alternative strategies that engage the arts, technology, or social media. There has been relatively little attention to how these interventions might be classified. The Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Group conducts extensive work systematically reviewing evidence supporting KT and has grouped interventions in a framework (http://whatiskt.wikispaces.com/EPOC+framework). This framework focuses on organizing interventions into subgroups including professional, financial, regulatory, and organizational interventions, and classifies target audiences as providers, patients, or structures. A taxonomy developed by the first author classifies KT activities according to their target audience and goal of the intervention. Tools and interventions should be classified by the target audience to whom they are directed (lay public/patient population, clinician/healthcare provider, and policy or decision maker) since the design principles and effectiveness might vary across different target audiences. For example, a summary of the evidence for patients will look quite different than one developed for a clinician or a policy decision maker. Tools can be devised to help identify new knowledge, evaluate/ synthesize existing knowledge, support decision-making, facilitate the process of change, operationalize implementation, or guide quality/outcome monitoring. Table 3 outlines definitions and examples.

Taxonomy for KT to Implement Evidence. Selected Examples of Tools Applying to Management of Neck Pain are Given

| KT Intervention Taxonomy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level of Action To support moving evidence into practice. | TARGET AUDIENCE (Intended Knowledge User)* | |||||

| Lay Public or Patient Population | Clinician Healthcare Provider | Policy/Decision-Maker | Industry | Other | ||

| Increase awareness of a problem- evidence to practice gap Tools/interventions that focus on making the target audience aware of the importance/ implications of a problem, or the gap between evidence and practice. | Public awareness campaigns Informational brochures Mass media* | Targeted information about gaps in meeting practice standards Networking | Policy briefs Legislative action Campaigns Petitions | Health Forum and Dialogue on Chronic Pain http://www.mcmasterhealthforum.org/images/docs/engaging%20health%20system%20decision-makers%20in%20supporting%20chronic%20pain%20management_dialogue-summary_2011-06-14.pdf | ||

| Acquire evidence-based knowledge Tools/interventions designed to locate or access health research or research-informed information; this includes push out or dissemination of evidence. | Website with evidence-based information, or lay summaries of new research studies | Evidence resources such as Evidence Updates MacPlus (push out of evidence): http://plus.mcmaster.ca/MacPLUSFS/Default.aspx?Page=1 Distribution of educational materials* Educational outreach * Local opinion leader* | Evidence resources for policymakers | |||

| Evaluate/synthesize evidence Tools/interventions that support or develop evidence synthesis i.e., compile, appraise, or synthesize the best research information on a topic. | Tools/processes to help the lay public find evidence-based information and evaluate its quality. DISCERN a tool for the public to discriminate between websites: http://www.discern.org.uk/ | Tools/processes that provide or synthesize information on etiology/prevalence, diagnosis, treatment, prognosis, or outcome evaluation for clinicians, and/or help clinicians identify the quality of primary or synthesized evidence. Critical appraisal tools for different study types; databases or push out of pre-synthesized/evaluated evidence; systematic reviews or clinical practice guidelines. Neck pain CPG: http://www.jospt.org/issues/articleID.1454/article_detail.asp Use of opioids: http://nationalpaincentre.mcmaster.ca/opioid/ | Tools/processes that provide or synthesize information for policymakers, or help policymakers identify the quality of primary or synthesize health policy evidence. Policy briefs; Databases or push out of pre-synthesized/evaluated evidence. | |||

| Make an evidence-informed decision Tools/interventions that assist in the application of health research evidence to decision-making including choosing between options (e.g., decision support tools, risk/benefit calculators), or that apply evidence to a specific person or context (e.g., decision aids that combine evidence with patient values/preferences). | Patient decision aid for receiving neck manipulation for neck pain: http://www.physio-pedia.com/Neck_Pain_Patient_Decision_Aid:_Step_6 | Clinical prediction rule for thoracic manipulation for neck pain. http://www.ispje.org/showcases2009/PTJ.pdf Local Consensus Process* Reminders* | Policy briefs Policy-researcher | |||

| Adapt evidence to context Tools/interventions designed to help users to adapt research evidence or evidence-informed information to make is relevant, useful, or implementable within a given context; this includes assessment of needs/barriers and modification of evidence to context. | PARiHS self assessment tool Audit and feedback* http://www.implementationscience.com/content/6/1/99 | PARiHS self assessment tool Formal integration of services* Skill Mix Changes* | ||||

| Implement specific actions(Implementation fidelity/scalability) Tools/interventions that focus on the operational aspects of implementing/executing specific actions that are defined by best evidence; e.g., ensure that implementation maintains intervention fidelity, scaling up from demonstration project to widespread use. | Tools: audiovisual, web-based, print tools, or other devices that describe specific evidence-based actions (what, when, how, where) in a format for patient use. | Tools: audiovisual, web-based, print tools, or other devices that describe specific evidence-based actions (what, when, how, where) to facilitate fidelity to evidence, e.g., training interventions or manuals, implementation checklists, audit processes. Exercise toolkit: http://www.physio-pedia.com/Manual_Therapy_and_Exercise_for_Neck_Pain:_Clinical_Treatment_Tool-kit?title=Physiopedia:Copyrights | Structural interventions* | |||

| Facilitate the process of change Tools/interventions that facilitate the general aspects of change**. These are generic strategies that help individuals or contexts to be better able to change. Tools can be designed to be self/internally initiated (by the target audience) or externally driven (applied to the target audience). | Generic: tools that support the change process Internal: change guides, self-tracking tools External: reminders, incentive/penalty systems, audit and feedback | |||||

| Process or outcome evaluation/ monitoring Tools that focus on selecting or implementing processes and measures to assess the impact of evidence-informed practice changes. This can include monitoring the process, health effects, or cost-effectiveness (at the individual, group or population level) of implementation. | Tools designed for patients to monitor progress of adherence to evidence-based actions. | Audiovisual, web-based, print tools, or other devices that capture the specific consequences of actions taken. This can include: defining specific outcome measures, the process (standardization criteria/timing), etc. Electronic record mining; outcomes monitoring/databases | Implant/device or drug monitoring/reporting tools | |||

This KT taxonomy is organized to classify the purposes of the KT interventions that move knowledge into action. Interventions can have more than one element or purpose. However, this taxonomy can facilitate thinking about how different strategies might be selected. Users should consult KT resources and other taxonomies to find different KT interventions and determine the supporting evidence when making these choices. Strategies that have been studied by the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care group through publication of systematic reviews are denoted by * (http://epoc.cochrane.org/our-reviews).

DISCUSSION

KT is an evolving field and there is substantial evidence emerging about how to move evidence-based recommendations into clinical practice. The Cochrane collaboration group that reviews KT research has published more than 70 systematic reviews (http://epoc.cochrane.org/) on this topic. Multiple reviews indicate that moderate changes in practice can be expected with specific KT strategies and tools. It is ideal if best practice in tool development includes using theoretical frameworks, evidence about how to optimize communication, KT evidence, and clinical expertise. KT tools should integrate best evidence into practical tools that fit into everyday practice. If these can be accomplished and appropriately disseminated, they have potential to make substantial improvements in practice. However, a challenge is that such high-quality tools can be time-consuming to create. It is not clear who bears the burden of this creation since often the research enterprise and academic institutions do not fund or promote this activity. Nevertheless, it is critical that KT be pursued, if the potential benefit of new evidence-based interventions is to be manifested as improved clinical outcomes. This is particularly important with respect to neck pain given that suboptimal outcomes have been documented both in terms of quantitative outcomes and qualitative studies that demonstrate patient dissatisfaction with the current delivery of care for their neck pain [75].

We highlight two specific examples that are highly relevant to implementation of evidence in neck pain. The information contained in the ‘Manual therapy and exercise for neck pain: clinical treatment tool-kit’ is drawn from three of the COG systematic reviews that included 60 randomized controlled trials on manual therapy and exercise for neck pain. This toolkit (http://www.physio-pedia.com/Neck_Pain_ Tool-kit:_Step_1) was produced in association with the International Collaboration on Neck overviews published in this issue. It utilizes tables, pictures, and symbols to depict key positive or negative findings for specific techniques, dosages, and outcomes. Specific neck pain disorder types (whiplash associated disorder, cervicogenic headache, radiculopathy), duration of disorder (acute, subacute, chronic) and follow-up periods (short, intermediate, and long-term) are differentiated to characterize the findings to support management of subtypes of neck pain. This toolkit has not been formally evaluated, but treatment recommendations are based on the Cochrane GRADE approach [76]. This toolkit should be applied judiciously. We suggest this tool be used as a resource to inform treatment decisions, not to dictate them. The impact of this or other practical tools for neck pain KT is yet to be determined.

Other tools can be used in neck pain care. Patient Perspectives (http://www.jospt.org/issues/perspectives.asp) summarize individual research studies for lay audiences and may enhance communication about research evidence with patients when making a shared decision about the treatment plan. Since exercise is a fundamental component of managing neck pain, apps that appropriately specify and facilitate these exercises might be useful to both patients and clinicians. Further, such an approach might reduce variation care. Conceptually this tool development has potential to enhance practice, however, there is not yet specific evidence to support these efforts.

This paper on KT highlighted theoretical and evidence foundations that support tool development and implementation as a means of promoting evidence-based practice for neck pain. Evidence on the effectiveness of tools and how to optimize their impact is in its infancy. Researchers need to be more aware of creating useful evidence-based tools, or collaborating with knowledge users to develop such tools, if the benefits of health research are to be achieved. Clinicians and researchers need to familiarize themselves with the language used to describe and the methods needed to successfully take evidence to practice—knowledge into action.

KEY MESSAGES

- The benefits of EBP depend on knowledge translation—moving knowledge into action.

- There is a substantial gap between how neck pain is currently managed and best evidence in management of neck pain.

- KT tools are a critical component of the knowledge to action cycle.

- Development of KT tools requires a theoretical framework, evidence about the barriers to change, and a structured approach to mitigate those barriers.

- KT/tools can have different goals and target audiences—these features can help classify the type of KT.

- Evidence-based tools specific for neck pain have been developed.

- KT presumes providing the right information, in the right format, at the right time. Evidence-based tools can assist in this process.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.