All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Biomarkers in Arthroplasty: A Systematic Review

Abstract

We performed a systematic review of all MEDLINE-published studies of biomarkers in arthroplasty. Thirty studies met the inclusion criteria; majority evaluated biomarkers for osteolysis, aseptic prosthetic loosening, and prosthetic infections. Four studies reported an elevated Cross-linked N-telopeptides of type I collagen (urine or serum) in patients with osteolysis or aseptic prosthetic loosening when compared to appropriate controls. Two or more studies each found elevated C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and interleukin-6 in patients with infected prosthetic joints compared to controls. Most other biomarkers were either examined by single studies or had inconsistent or insignificant associations with outcomes. We conclude that the majority of the biomarkers currently lack the evidence to be considered as biomarkers for arthroplasty outcomes. Further studies are needed.

INTRODUCTION

Total hip and knee arthroplasty (THA and TKA) represent a major advance in the treatment of refractory hip/knee joint pain. TKA and THA are performed very commonly and are projected to increase dramatically in numbers in the next two decades [1]. Increasing longevity, earlier age at arthroplasty, and excellent pain and functional outcomes with these procedures are cited as reasons for the increasing incidence of these procedures. A number of patients, however, have suboptimal outcomes. Complications may include refractory pain, peri-prosthesis osteolysis with aseptic loosening, heterotopic ossification, and infection, which may result in a failed arthroplasty. Evaluation for complications of arthroplasty are primarily clinical, with few prognostic or diagnostic tests easily available that allow early identification of this subgroup of patients with suboptimal outcomes.

Biomarkers are objective indicators of biologic processes, pathologic processes or pharmaceutical responses to therapeutic interventions [2]. A number of studies have assessed the prognostic and diagnostic utility of biomarkers in improving evaluation of outcomes following arthroplasty. The purpose of this systematic review is to summarize the data from the literature regarding biomarkers for arthroplasty outcomes. We specifically evaluated if there are any valid biomarkers for osteolysis or loosening of the prosthesis, prosthetic infections, pain/stiffness following arthroplasty, or other complications following arthroplasty.

METHODS

Study Design

All English language studies investigating biomarkers for various clinical outcomes of arthroplasty in humans were included in this review. Exclusion criteria included case reports, meta-analyses, and reviews. Studies that evaluated short term post-operative changes in biomarkers, biomarker changes related to medical therapies following arthroplasty, thromboembolic outcomes, and studies limited to pathology only were excluded as they were felt to be beyond the scope of this review.

Search Methods for Identification of Studies

A Cochrane librarian searched the MEDLINE electronic bibliographic database up to July 2008 using the MeSH terms “arthroplasty”, “replacement” and “biomarkers” and similar terms. The reference lists of identified publications were reviewed to identify any additional studies (Appendix 1 and 2).

Data Collection

Two reviewers (MM and JS) independently applied inclusion/exclusion criteria to all potential studies and extracted data and outcomes using a standardized form. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion between the two reviewers, referring to a third party if necessary. Review authors were not blinded to any features of studies, since unblinding has minimal impact on selection bias [3].

From each study, we extracted the following data – (1) study population, (2) methods and details of any interventions, (3) type of arthroplasty and implant, knee vs hip vs other, cemented vs noncemented, primary vs revision, and (4) types of biomarkers evaluated. Outcome data were extracted, where possible, as raw numbers, plus any summary measures where standard deviations or confidence intervals were given. If no raw results were available, specific outcomes were described in detail.

RESULTS

Eligible Studies

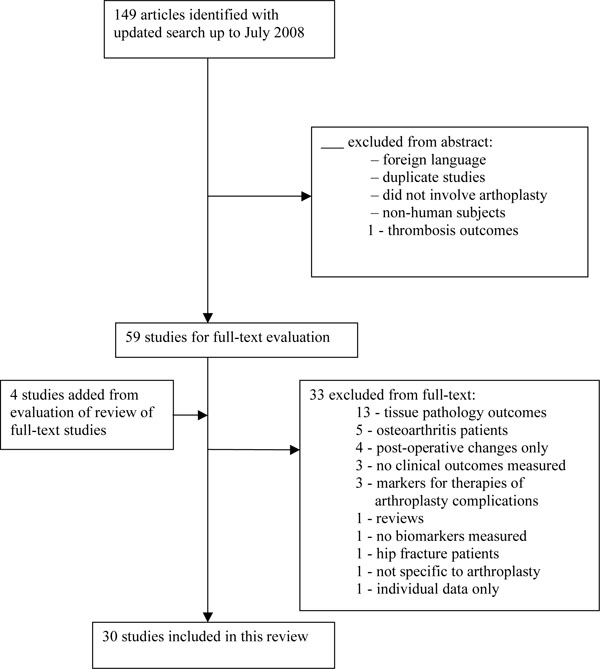

A total of 105 articles met initial criteria from the initial MEDLINE search completed in June 2007. The search was updated in July 2008 and a total of 149 articles were identified (Fig. 1). A total of 30 studies met inclusion/exclusion criteria, 26 from the original search and four additional studies from the reference lists of these studies.

Summary of screening of eligible studies.

Osteolysis

A total of five studies evaluated biomarkers for osteolysis following knee or hip arthroplasty (summarized in Table 1). Most comparisons were made to populations with arthroplasty with no osteolysis and to healthy controls without arthroplasty.

Summary of screening of eligible studies.

| Outcome | Study (Hip, Knee, Both) | Osteolysis | No Osteolysis | Healthy Control | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | p-Value | n | Mean (SD) | p-Value | ||

| Collagen peptides | |||||||||

| Urinary cross-linked N-telopeptide of type I collagen | Antonioiu 2000 (hip) | 11 | NA | 8A | NA | p = 0.002 | 7 | NA | p = 0.0297 |

| Von Schewelov 2006 (hip) | 33 | 34 bone collagen equivalents (BCE)/nM creatinine (12) | 127A | 29 BCE/nM Cr (15) | p = 0.06 | ||||

| Serum C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen | Arabmotlagh 2006 (hip) | 53 | Significant correlation found between bone mineral density loss in ROI 7 at 1 year with week 3 CTX-1 values (p = 0.002) | ||||||

| Chemokines, Cytokines & other | |||||||||

| Interleukin (IL)-1β | Fiorto 2003 (hip) | 8 | 2.15pg/ml (1.37) | 10A | 2.26pg/ml (0.89) | p = 0.96 | 17 | 2.02pg/ml (1.25) | p = 0.79 |

| Hernigou 1999 (hip) | 6 | “Undetectable” | 10B | NA | NA | 5 | “undetectable” | NA | |

| Tumor Necorsis Factor-α | Fiorto 2003 (hip) | 8 | 4.32pg/ml (5.2) | 10A | 3.84pg/ml (1.13) | p = 0.62 | 17 | 3.42pg/ml (2.12) | p = 0.95 |

| Hernigou 1999 (hip) | 6 | “undetectable” | 10B | NA | NA | 5 | “undetectable” | NA | |

| IL-6 | Fiorto 2003 (hip) | 8 | 2.86pg/ml (1.95) | 10A | 4.58pg/ml (4.02) | p = 0.24 | 17 | 3.88pg/ml (2.72) | p = 0.36 |

| Hernigou 1999 (hip) | 6 | 41pg/ml (17) | 10B | 22pg/ml (6.7) | p = 0.002 | 5 | NA | NA | |

| IL-11 | Fiorto 2003 (hip) | 8 | 0pg/ml (0) | 10A | 1.22pg/ml (2.57) | p = 0.27 | 17 | 18.69pg/ml (10.55) | p = 0.001 |

| transforming growth factor (TGF)-β | Fiorto 2003 (hip) | 8 | 23175pg/ml (8774) | 10A | 21120pg/ml (13657) | p = 0.50 | 17 | 23615pg/ml (10681) | p = 0.88 |

| matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1) | Fiorto 2003 (hip) | 8 | 3.69pg/ml (1.75) | 10A | 4.10pg/ml (1.44) | p = 0.50 | 17 | 3.31pg/ml (1.7) | p = 0.52 |

| prostaglandin E-2 (PGE-2) | Fiorto 2003 (hip) | 8 | 1330pg/ml (1097) | 10A | 2021pg/ml (1046) | p = 0.14 | 17 | 2893pg/ml (782) | p = 0.005 |

| Bone Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) | Arapmotlagh 2006 (hip) | 53 | No significant correlation found between bone mineral density loss in ROI 7 at 1 year with bone ALP values | ||||||

| Osteocalcin | Arapmotlagh 2006 (hip) | 53 | No significant correlation found between bone mineral density loss in ROI 7 at 1 year with osteocalcin values | ||||||

| C-reactive protein | Hernigou 1999 (hip) | 6 | 10mg/L (2.4) | 10B | 7.7mg/L (2.8) | p = 0.135 | 5 | NA | NA |

A Arthroplasty without osteolysis.

B Arthroplasty without osteolysis, >10 years post-op.

ROI = region of interest.

Collagen telopeptides:

Three studies evaluated collagen telopeptides as biomarkers for osteolysis following hip arthroplasty. Antoniou et al. [4] reported significantly higher urinary cross-linked N-telopeptides of type-T collagen in patients with osteolysis following hip arthropathy compared to controls. von Schewelov et al. [5] found a near significant increase in urinary cross-linked N-telopeptide in the osteolysis versus non-osteolysis group (p=0.06), which became significant after adjusting for age, gender, and time after surgery. Arabmotlagh et al. [6] found serum C-terminal telopeptides of type I collagen 3 weeks post-operatively to be significantly correlated with bone loss one year after hip arthroplasty.

Interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α):

Neither of the two studies that evaluated serum IL-1 β or TNF-α as a biomarker for osteolysis following hip arthroplasty found a significant difference between patients with osteolysis compared to controls [7, 8].

IL-6:

Two studies [7, 8] evaluated IL-6 as a biomarker for osteolysis following hip arthroplasty. Hernigou et al. [8] reported significantly higher IL-6 levels in patients with osteolysis compared to controls, while, in contrast, Fiorto et al. [7] did not find a significant difference in IL-6 levels with similar comparison groups.

Other:

Biomarkers evaluated by single studies included bone alkaline phosphatase (bone ALP) and osteocalcin [6]; IL-11, transforming growth factor-beta (TGF- β), matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1) and prostaglandin E-2 (PGE-2) [7]; and C-reactive protein (CRP) [8]. Only IL-11 was significantly lower in patients with osteolysis when compared to healthy controls and those without osteolysis.

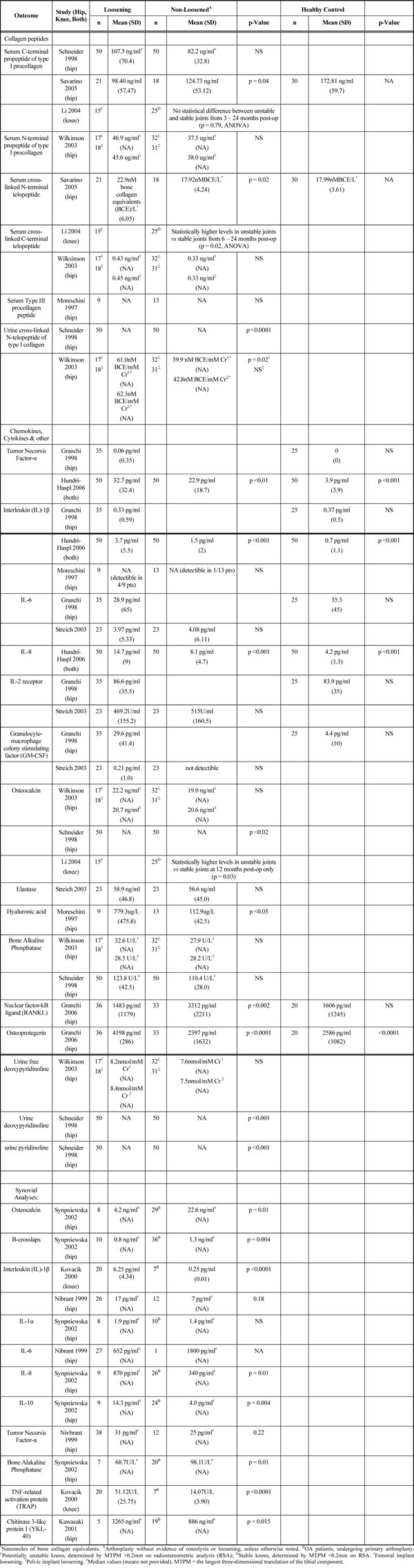

Loosening

A total of 14 studies evaluated biomarkers for loosening of the prosthesis following knee or hip arthroplasty compared to healthy controls or patients with non-loosened prostheses (summarized in Table 2). Nine studies evaluated serum biomarkers and five, synovial fluid biomarkers.

Summary of Biomarkers for Loosening of Prosthesis

|

Serum Biomarkers

Collagen Telopeptides:

Five studies evaluated various collagen peptides as a biomarker for prosthetic loosening. Serum levels of a C-terminal propeptide of type I procollagen (PICP) were not significantly different between clinically loosened hip prosthetic joints and controls [9] or between unfixed vs fixed knee protheses [10]. However, Savarino et al. [11] demonstrated a significantly lower PICP concentrations in loosened hip prostheses compared to stable hip implants. Serum N-terminal propeptide of type I procollagen (PINP) levels did not differ between patients with hip prostheis loosening and controls [12].

Savarino et al. [11] reported significantly higher serum cross-linked N-terminal telopeptide (NTx) levels in loosened hip protheses compared to controls. Li et al. [10] found significantly higher levels of serum cross-linked C-terminal telopeptides (ICTP) in unfixed knee arthroplasties when compared to fixed joints. Conversely, Wilkinson et al. [12] found no difference in ICTP levels between patients with loosened hip prostheses and controls. Moreschini et al. [13] found no significant difference in type III procollagen peptide levels in patients with loosened hip prostheses when compared to controls with osteoarthritis.

Schneider et al. [9] and Wilkinson et al. [12] both found significantly increased levels of urinary crosslinked N-telopeptides of type I collagen in patients with loosened hip arthroplasty when compared to stable prostheses.

TNF-α:

Two studies [14, 15] evaluated TNF-α as a biomarker for loosening of arthroplasty. Hundri-Haspl et al. [15] noted significant increase in TNF-α values in patients with loosened knee and hip arthroplasty when compared to controls, while Granchi et al. [14] found no difference in TNF-α levels in similar comparison groups.

IL-1β:

Three studies [13-15] evaluated serum IL-1β as a biomarker for arthroplasty loosening. Hundri-Haspl et al. [15] noted significant increase in IL-1β in patients with loosened knee and hip arthroplasty when compared to controls. Granchi et al. [14] did not find a difference in IL-1β when comparing loosened hip arthroplasty to healthy controls. However, on subgroup analysis, they found a significant increase in IL-1β in patients with loosened titaniumaluminium-vanadium (TiAIV) cemented hip prostheses in comparison to healthy controls as well as loosened cobalt-chromium (CrCoMo) hip implants (cemented and uncemented) and uncemented TiAIV implants. Moreschini et al. [13] reported detectable IL-1β in 4 of 9 patients with loosened hip implants compared to only 1 of 13 patients with fixed hip implant and 0 of 13 patients with OA prior to arthroplasty, though no statistical analysis was performed.

IL-6:

Two studies [14, 16] found no significant differences in IL-6 levels in patients with loosened hip arthroplasty compared to controls.

Granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF):

Streich et al. [16] demonstrated detectible levels of GM-CSF in only 1 of 23 patients with loosened hip arthroplasty and in 0 of 23 of fixed hip implant patients. Granchi et al. [14] reported significantly higher levels of GM-CSF in patients with a loosened hip arthroplasty when compared to healthy controls. This significant increase was demonstrated in all subgroups (cemented/uncemented TiAIV implants, cemented CrCoMo implants) except loosened uncemented CrCoMo implants which were similar to controls.

Osteocalcin:

Schneider et al. [9] reported significantly higher osteocalcin levels in loosened versus stable prostheses, while Wilkinson et al. [12] found no difference with the same comparison. Li et al. [10] found significantly higher osteocalcin levels in patients with potentially unstable knee prostheses compared to patients with stable implants at 12 months, but no differences were noted at 24 months.

Bone alkaline phosphatase (ALP):

Bone-specific ALP levels were similar in patients with and without loosening of hip prosthesis in two studies [9, 12].

Urine deoxypyridinoline:

Schneider et al. [9] found significantly higher urine deoxypyridinonline levels in patients with loosened hip implants compared to stable implants, while Wilkinson et al. [12] reported no significant difference in similar comparison groups.

IL-2 receptor:

Two studies [14, 16] found no significant differences in IL-2 receptor concentrations in patients with prosthesis loosening compared to controls.

Other:

The evidence for each of the following was based on single studies. Significantly higher levels of osteoprotegerin (OPG) and RANKL [17], hyaluronic acid [13], urine pyridinoline [9] and IL-8 [15] were found in patients with loosened hip implants compared to their respective controls. Elastase levels were not significantly different between patients with loosened implant and controls [16].

Synovial Biomarkers

Four studies evaluated various biomarkers in synovial fluid as a marker for loosening of the prosthetic joint when compared to controls.

IL-1β:

Nivbrant et al. [18] found significantly higher synovial IL-1β in loosened hip implants compared to osteoarthritis patients, but were similar to patients with fixed hip prostheses. Similarly, Kovacik et al. [19] reported significantly higher synovial IL-1β levels in patients with loosened knee prostheses compared to osteoarthritis patients.

Other:

Nivbrant et al. [18] demonstrated significantly higher synovial TNF-α levels in loosened prosthetic hip joints when compared to OA patients, though not when compared to fixed hip implants. Synovial IL-6 levels were similar between all of these groups, though too few observations were available for comparisons. Kawasaki et al. [20] noted significantly higher YKL-40 levels, a growth factor for chondrocytes and fibroblasts, in failed hip implants when compared to OA patients, though these levels were similar to patients with osteonecrosis of the hip. Other biomarkers found to be significantly elevated in loosened prostheses when compared to OA patients in single studies were TNF-related activation protein (TRAP) concentrations [19], IL-8 [21], and IL-10 [21]. Lower concentrations of osteocalcin, B-crosslaps, and bone ALP were also noted in loosened hip prostheses when compared to OA patients in a single study [21]. IL-1α concentrations were similar in both groups [21].

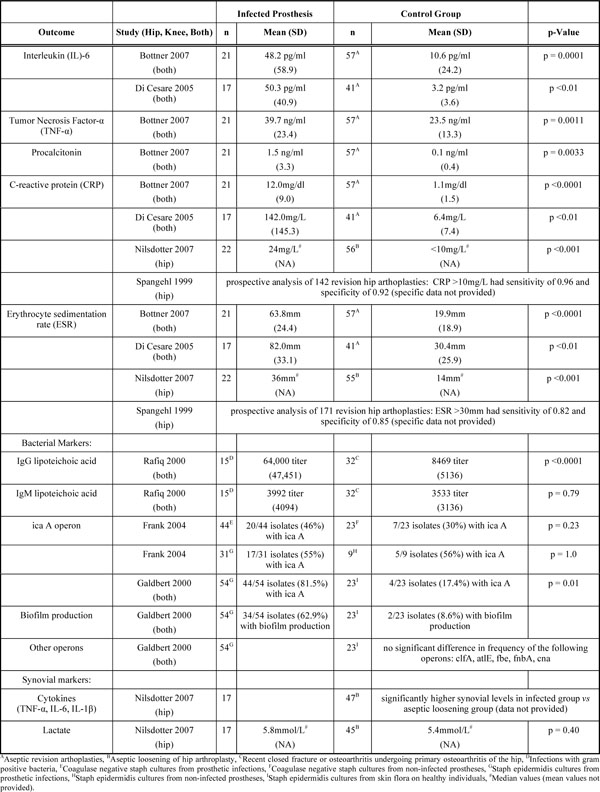

Prosthetic Infections

A total of seven studies evaluated biomarkers for infection of the prosthesis following knee or hip arthroplasty (summarized in Table 3). Three studies, Rafiq et al. [22], Galdbert et al. [23], and Frank et al. [24] evaluated markers for specific infections of prosthetic joints and four studies evaluated diagnostic biomarkers for prosthetic infections.

Summary of Biomarkers for Infected Prostheses

|

C-reactive protein (CRP) and Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR):

Three separate studies [25-27] each found significantly higher CRP and ESR levels in patients infected prosthetic joints compared to aseptic revisions. Spangehl et al. [28] prospectively analyzed patients undergoing hip revisions and noted a sensitivity of 0.96 and specificity of 0.92 for CRP levels >10 mg/L for infected versus aseptic revisions. For ESR>30, the respective sensitivity was 0.82 and specificity, 0.85.

IL-6:

Two studies [25, 26] each noted significantly higher levels of serum IL-6 in infected prosthetic joints when compared to aseptic joints undergoing revision arthroplasty.

Other cytokines:

Bottner et al. [26] noted elevated levels of serum TNF-α and procalcitonin in patients with infected prosthetic joints compared to aseptic prosthetic revisions.

Synovial fluid markers:

Nilsdotter et al. [27] noted significantly higher synovial fluid concentrations of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 in those with infected prosthetic hip joints when compared to aseptic controls.

Bacterial markers:

Galdbert et al. [23] evaluated bacterial genes from Staphylococcus epidermidis strains cultured from prosthetic infections as compared to S. epidermidis strains from skin flora of healthy controls. They found significantly greater frequency of biofilm production and the ica A operon in infected prostheses. In contrast, Frank et al. [24] found no difference in frequency of the ica A operon in coagulase-negative staph species cultured from prosthetic infections in comparison to strains obtained from prosthetic joints without evidence of infection.

Rafiq et al. [22] reported significantly elevated titers of IgG to cellular lipoteichoic acid in patients with prosthetic joint infections as compared to patients with osteoarthritis or closed fractures. IgM titers were similar between these groups.

OTHER OUTCOMES

Pain/Stiffness

Hall et al. [29] found a significant correlation between peak CRP levels post-operatively and pain at time of discharge as well as between peak IL-6 levels post-operatively and time to be able to ambulate 10 and 25m following hip arthroplasty. No significant correlations were found between CRP or IL-6 levels post-operatively to 1 and 6 month Western Ontario and McMaster universities osteoarthritis index (WOMAC) values, a measure of arthritis-related disability.

Wozniak et al. [30] prospectively found significantly higher nitrous oxide (NO) production from stimulated peripheral neutrophils 2 months and 2-3 years post-operatively in patients with pain compared to patients without pain following primary knee or hip arthroplasty.

Heterotopic Ossification

Wilkinson et al. [31] noted significantly greater levels of C-telopeptide of type-I collagen, osteocalcin, and N-terminal propeptide of type-I procollagen in patients who developed heterotopic ossification at 26 weeks when compared to those without ossification. No differences were noted in bone ALP, urinary cross-linked N-telopeptide of type-I collagen, and urinary free deoxypridinoline.

Polyethyelene Wear

Messieh et al. [32] noted a significant correlation between synovial lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels and polyethylene wear in eleven patients undergoing revision knee arthroplasty.

Hospital Outcomes

Ackland et al. [33] prospectively noted patients with a preoperative CRP >3mg/L had a significantly longer mean hospital stay as compared to those with CRP <3 mg/L (7.5 vs 6.0 days, respectively) following knee or hip arthroplasty.

DISCUSSION

This systematic review of biomarkers in arthroplasty summarized the findings from 30 studies of clinical outcomes following knee and/or hip arthroplasty. Despite the enormous success rates of knee and hip arthroplasties, patients may face a number of potential complications post-operatively and during long-term follow-up, including periprosthetic osteolysis, implant loosening, and joint infections. Diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers have the potential to provide an early, accurate, and noninvasive diagnosis of these undesired outcomes as well as help design interventions to prevent some of these complications.

The most frequently studied arthroplasty outcomes with regards to biomarkers were osteolysis and prosthesis loosening. Osteolysis and subsequent aseptic joint loosening is the most common reason for joint revision in hip arthroplasty in the United States.

In our review of the published literature, only cross-linked Ntelopeptides of type I collagen (NTX-1) (serum or urine) was significantly associated with loosening/osteolysis, in more than two studies with appropriate controls (without loosening/osteolysis and/or healthy controls) [4, 9, 11, 12]. Von Schewelov et al. found an insignificant difference between NTX-1 levels in patients with presence of osteolysis when compared to controls (p = 0.06), though became significant after adjustment for age, gender, and time after surgery.

Serum cytokines, such as serum IL-1 β or TNF-α, that have been suspected to be associated with development of osteolysis and loosening [35-38] had inconsistent associations with loosened prostheses [14, 15] and no association with osteolysis [7, 8]. We postulate that this may be due to lack of well-designed studies rather than lack of association. A significant immunological response occurs in the periprosthetic tissue in many patients with prosthetic loosening, and it has been thought that this inflammatory process may contribute to the development of osteolysis and aseptic loosening [35-38]. Other biomarkers for osteolysis or prosthesis loosening were either studied by single studies or had inconsistent or insignificant differences.

Prosthetic infections lead to significant morbidity, are difficult to diagnose, and may lead to significant disability. CRP and ESR, both of which are currently used clinically in the diagnosis and follow-up of patients with prosthetic joint infections, were consistently found to be significantly elevated in septic prosthetic joints as compared to aseptic joint revision controls in a number of studies [25-28]. Interleukin-6 was consistently found to be elevated in septic prostheses as compared to aseptic revision controls [25, 26].

A number of other arthroplasty outcomes included in this review, such as heterotopic ossification, pain following arthroplasty, post-operative hospital outcomes, and polyethylene wear, were evaluated only by one or two studies. Because of this, it is difficult to make adequate assessments for there potential use as biomarkers for these outcomes.

This review had a number of limitations, mostly related to limitations of the included studies. The large variability of the biomarkers measured in the included studies with only a few studies replicating the results for each biomarker in more than one study/population, limited our ability to draw conclusions for most biomarkers. The majority of the included studies were case control studies with small sample sizes, with half of the included studies containing <50 patients. A number of these studies measured multiple biomarkers at multiple outcomes, making them prone to type I error, i.e., finding a positive result just by chance. Well-designed studies of larger, welldefined cohorts are needed to improve our understanding of the utility of these biomarkers in predicting arthroplasty outcomes.

In conclusion, this review evaluated 30 studies that measured different biomarkers for knee and hip arthroplasty outcomes. While a few biomarkers – namely cross-linked N-telopeptides of type I collagen for prosthesis loosening or osteolysis and CRP, ESR, and IL-6 for infected prostheses – were found consistently significantly different from control groups in the included studies, most biomarkers lack the evidence to be considered adequate markers for the arthroplasty outcomes at the present time. However, this is an exciting area of research that has the potential to impact and improve arthroplasty outcomes. Further studies are necessary, likely with larger study populations and longer prospective follow-up, to determine which of these biomarkers will have clinical application in diagnosis and/or prognosis of arthroplasty outcomes.

GRANT SUPPORT

Supported by the NIH CTSA Award 1 KL2 RR024151-01 (Mayo Clinic Center for Clinical and Translational Research).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Indy Rutks of the Cochrane Library group at the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Medical center, Minneapolis for performing and updating the search.

Appendix 1

Search strategy for Systematic Review Performed in 2007 (Updated in July 2008)

Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R) <1950 to July Week 4 2007>

Search Strategy:

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

- Biological Markers/ or biomarkers.mp. (79469)

- exp Arthroplasty, Replacement, Knee/ or exp Arthroplasty, Replacement/ or exp Arthroplasty, Replacement, Hip/ or exp Arthroplasty/ or exp Arthroplasty, Replacement, Finger/ or exp Joint Prosthesis/ or arthroplasty.mp. (39802)

- 1 and 2 (125)

- limit 3 to english language (105)

Appendix 2

Summary of the Included Studies

| Study | Study Design/Level of Evidence | Comparisons | Outcomes | Other Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antonioiu 2000 | case control study/Level III | Hip osteolysis (n = 11), hip arthroplasty without osteolysis (n = 8), healthy controls (n = 7), hip osteolysis following alendronate therapy x6 weeks (n = 10) | Urinary cross-linked Ntelopeptide of type I collagen; | Longer average time from original operation in osteolysis group (8.8yrs) vs. fixed implants (2.4yrs) |

| Von Schewelov 2006 | case control study/Level III | Hip osteolysis (n = 33); hip arthroplasty without osteolysis (n = 127) | urinary cross-linked Ntelopeptide of type I collagen | Post-operative time in osteolysis was 73 months vs. 42 months in nonosteolysis group. |

| Arabmotlagh 2006 | Prospective cohort study/Level II | 53 patients with unilateral THA for OA; followed with bone density scans on 2, 4, 6, and 12mos post-op and correlated to marker measured at 3, 6, 16, and 24 weeks post-op. | Serum C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen; bone ALP, osteocalcin | Numerous comparisons from BMD and biomarkers lessen reliability of findings. |

| Hernigou 1999 | case control study/Level III | Hip osteolysis, >10yrs postop (n = 6); hip arthroplasty without osteolysis, >10yrs post-op (n = 10); hip arthroplasty without osteolysis, <6yrs post-op (n = 6); healthy controls (n = 5) | IL-B, TNF-a, IL-6, CRP | |

| Fiorito 2003 | case control study/Level III | Hip osteolysis (n = 8); hip arthroplasty without osteolylsis (n = 10); healthy controls (n = 17) | IL-1B, IL-6, TNF-a, TGF-B, PGE-2, MMP-1, IL-11 | |

| Schneider 1998 | case control study/Level III | Aseptic loosening of hip implant (n = 50); fixed hip implant (n = 50) | Bone ALP, osteocalcin, serum C-terminal propeptide of type I procollagen, urine crosslinked N-telopeptide of type I collagen, urine pyridinoline, urine deoxypyridinonline | |

| Savarino 2005 | case control study/Level III | Aseptic loosening of hip implant (n = 21), fixed hip implant (n = 18), OA patients at time of primary arthroplasty (n = 17), healthy controls (n = 30) | Serum cross-linked Ntelopeptide of type I collagen, serum C-terminal propeptide of type I procollagen | Healthy controls not matched for age or gender and not used in statistical comparisons |

| Li 2004 | prospective cohort study/Level II | 45 patients followed prospectively after TKA; biomarker measured at 1 week and 3, 6, 12, and 24 months post-op; compared to quality of fixation measured by RSA1 – MTPM2 >0.2mm represented unstable fixation, <0.2mm represented stable fixation | serum C-terminal propeptide of type I procollagen; serum cross-linked C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen; osteocalcin | A part of an 80 patient randomized prospective study comparing cemented to uncemented fixation of tibial component for TKA, 45 agreed for blood tests; excluded patients without RSA data at 1 or 2 years (5 patients) |

| Wilkinson 2003 | case control study/Level III | Aseptic loosening of hip implant (n = 26); stable fixation of hip implant (n = 23) | Bone ALP, serum cross-linked C-terminal telopeptide, osteocalcin, serum N-terminal propeptide of type I procollagen, urine cross-linked N-telopeptide of type I collagen, free deoxypyridinoline | Only provided data for either femoral or pelvic loosening when compared to fixed implants |

| Moreschini 1997 | case control study/Level III | Aseptic loosened hip prosthesis (n = 9); fixed hip prosthesis (n = 13); OA patients prior to primary arthroplasty (n = 13) | Hyaluronic acid, IL-1B, type III procollagen peptide | |

| Granchi 1998 | case control study/Level III | Aseptic loosening of hip prosthesis (n = 35), healthy controls (n = 25) | IL-1a, IL-1B, IL-6, GM-CSF, IL-2 receptor, TNF-a | Differentiated failed arthoplasties to those with CrCoMo or TiAIV components |

| Hundri-Haspl 2006 | case control study/Level III | Large joint implant loosening (n = 50), large joint arthroplasty without loosening (n = 50), candidates for arthroplasty from advanced OA (n = 50), healthy controls (n = 50) | IL-1B, IL-8, TNF-a | Specific type of large joint prostheses not reported |

| Streich 2003 | case control study/Level III | Aseptic loosening of hip prosthesis (n = 23), fixed hip prosthetic implant (n = 23) | IL-6, GM-CSF, elastase | Significantly more males in healthy donors |

| Granchi 2006 | case control study/Level III | Aseptic loosening of hip implant (n = 36), fixed hip implant (n = 33), severe OA prior to arthroplasty (n = 39), healthy subjects (n = 20) | Osteoprotegerin, RANKL | Significantly more males in healthy donors; significantly longer duration for post-op evaluation in loosening (112 mos) vs. stable joint (32 mos) |

| Synpniewska 2002 | case control study/Level III | aseptic loosening of hip implant (n = 10); primary OA patients undergoing primary arthroplasty (n = 39) | synovial levels: osteocalcin, B-crosslaps, IL-1a, IL-8, IL-10 | no fixed arthroplasty control group; excluded patients from analysis if missing outcome data |

| Kovacik 2000 | case control study/Level III | hip implant revisions (n = 20); primary OA patients undergoing primary arthroplasty (n = 7) | synvoial levels: TRAP, IL-1B | does not specific reasions for hip implant revions |

| Nivbrant 1999 | case control study/Level III | loose hip prosthesis (n = 38), fixed hip arthroplasty (n = 12); OA patients undergoing primary arthroplasty (n = 38) | synovial levels: IL-1B, TNF-a, IL-6 | mean time from implantation for loose prosthetics was 9.8yrs vs. 2.8yrs in fixed implant; excluded patients from analysis if missing data; median data only |

| Kawasaki 2001 | case control study/Level III | loosened hip prosthesis (n = 5), OA patients from primary hip dysplasia (n = 19), osteonecrosis of femoral neck (n = 21) | synovial levels: YKL-40 | average age for OA patients was 48 vs. 63 in loosed implant group; median data only |

| Nildotter 2007 | case control study/Level III | infected hip implants (n = 25), loosened hip implant (n = 60), OA patients undergoing primary arthroplasty (n = 46) | synovial levels: lactate, TNFa, IL-1B, IL-6 serum levels: CRP, ESR, IL-6, TNF-a, IL- 1B | no data provided on serum cytokine levels collected; no comparisons to OA control group provided; excluded patients from analysis if missing data |

| Bottner 2007 | case control study/Level III | septic revision for large joints (n = 21); aseptic revision of large joints (n = 57) | CRP, ESR, IL-6, TNF-a, procalcitonin | Knee/hip revisions: 5/16 for septic, 23/34 for aseptic |

| Frank 2004 | case control study/Level III | staph cultures from prosthetic joint infections compared to coag (-) staph cultures from non-prosthetic joint infections | icaADBC operon | |

| Galdbert 2000 | case control study/Level III | staph epidermidis strains from prosthetic infections (n = 54), staph epidermidis strains from skin flora from 8 healthy individuals | ica operon, biofilm production, genes: clfA, atlE, fbe, fnbA, cna | |

| Di Cesare 2005 | case control study/Level III | 58 patients undergoing reoperation of hip or knee: 17 patients with septic prosthetic infection; 41 patients without evidence of infection | CRP, ESR, IL-6 | |

| Rafiq 2000 | case control study/Level III | patients with prosthetic infection from gram positive organisms (n = 15), control group of 32 patients – 21 with closed fracture, 11 with primary OA | IgG and IgG to lipoteichoic acid | |

| Spangehl 1999 | prospective cohort study/Level II | prospectively evaluated 178 patients undergoing revision hip replacements | determined specificity, sensitivity for CRP, ESR in prosthetic infections | no specific data provided for comparison analysis; excluded patients from analysis if missing data |

| Hall 2001 | prospective study/Level II | 102 patients undergoing primary THA | serum levels: norepinephrine, epinephrine, cortisol, IL-6, CRP; pain, function, and WOMAC3 at 1 and 6 months; | |

| Wozniak 2004 | prospective cohort study/Level II | 33 patients undergoing primary TKA or THA due to OA, divided amongst those experiencing pain (n = 8) and no pain (n = 25) after 2-3 years; 14 healthy controls | neutrophils isolated from peripheral blood and analyzed for NO production – at basline, 2 weeks, 2 months, and 2-3 years post-operatively; | no apparent tool for pain assessment provided; 5/8 reporting pain had evidence of loosening |

| Messiah 1996 | prospective cohort study/Level II | 11 patients undergoing revision TKA; ruled out infection; | synovial LDH levels and correlated to presence of polyethyelene wear | no control group; no apparent standardized method for measurement of polyethyelene wear reported |

| Wilkinson 2003 | case control study/Level III | 20 patients undergoing primary THA or OA; compared development of heterotopic ossification by 26 weeks (n = 9) with those without evidence of such (n = 11) | N-terminal propeptide of type- I procollagen, osteocalcin, bone ALP, C-telopeptide of type-I collagen, urine crosslinked N-telopeptide of type-I collagen and free deoxypridinoline | no control group; only 26 weeks followup for development of heterotopic ossification |

| Ackland 2007 | prospective cohort study/Level II | 129 patients undergoing THA or TKA, divided amongst those with hsCRP >3mg/L (n = 63) and those with hsCRP <3mg/L (n = 66) | length of stay, morbid events |

1 RSA = radiostereometric analysis

2 MTPM = the largest three-dimensional translation of the tibial component

3 WOMAC = Western Ontario and McMaster universities osteoarthritis index

Level of evidence based on University of Oxford Center for Evidence-based medicine:Level 1: Testing of previously developed diagnostic criteria in series of consecutive patients (with universally applied reference "gold" standard); Systematic review of Level-I studies

Level 2: Development of diagnostic criteria on basis of consecutive patients (with universally applied reference "gold" standard); Systematic review of Level-II studies

Level 3: Study of nonconsecutive patients (without consistently applied reference "gold" standard); Systematic review of Level-III studies

Level 4: Case-control study; Poor reference standard

Level 5: Expert opinion