All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Sternoclavicular Joint Reconstruction with Semitendinosus Allograft and Suture Anchors after Recurrent Posterior Dislocation in a Professional North American Football Player

Abstract

Background:

Posterior sternoclavicular joint dislocations are an extremely rare but potentially life-threatening injury that can occur in sports. A variety of surgical procedures have been proposed, but there is no consensus on the treatment of choice. It is also largely unknown if a safe return to high-risk sports is possible.

Case Presentation:

We present a case of a posterior sternoclavicular joint dislocation in a 22-year-old male professional North American football player who had a recurrent irreducible posterior dislocation after initial injury management by closed reduction. The patient’s desire to return to football presented unique challenges to management. His sternoclavicular joint was subsequently reconstructed with semitendinosus allograft in a figure-of-eight augmented with suture anchors. After recovery, he returned to play as a running back in professional football symptom-free.

Conclusion:

Our patient's successful return to playing professional football after the sternoclavicular joint reconstruction suggests that this should be considered an effective treatment option when managing posterior sternoclavicular dislocation in high level contact sports players.

1. INTRODUCTION

Sternoclavicular (SC) joint dislocations are an extremely rare injury accounting for less than 1% of all traumatic joint dislocations [1]. Anterior SC joint dislocations are 20% more common [2] and rarely problematic, whereas posterior SC joint dislocations are associated with a high incidence of morbidity and mortality due to the joint's close proximity with mediastinal structures. Posterior SC joint dislocations are a medical emergency requiring prompt reduction, however, controversy exists in management. Attempts at closed reduction have a high incidence of failure [3-5], and open reduction and surgical stabilization is indicated for irreducible or recurrent cases [6-8]. A variety of techniques have been proposed, but there is no consensus on the treatment of choice.

Sports injuries are the second most common cause of posterior SC joint dislocation [9, 10]. North American football poses a high risk for posterior SC joint dislocation because of the protracted position of the arm and the frequent, high impact collisions to the chest and shoulder [1]. Due to this increased risk in football players and the morbidity and mortality associated with this injury, there should be an increased concern for stability to resume such high risk contact activities. Most previous reports in the literature have focused mainly on the diagnosis and management, while neglecting to mention if a safe return to high risk contact sports was possible.

We present a case of a posterior SC joint dislocation in a professional North American football player who had a recurrent irreducible posterior dislocation after initial injury management by closed reduction. The patient’s desire to return to professional football presented unique challenges to management. His SC joint was subsequently reconstructed with semitendinosus allograft and suture anchors, and he successfully returned to play professional football. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of this entity in a professional North American football player.

2. CASE REPORT

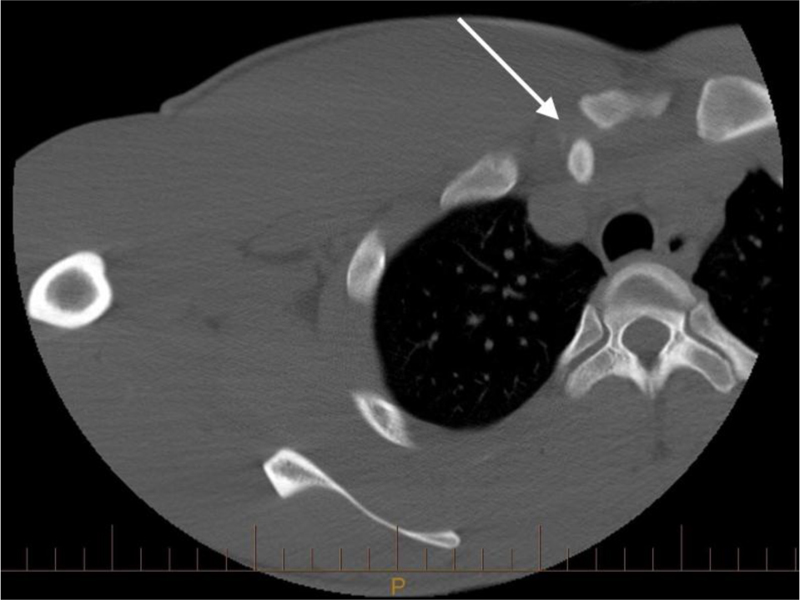

A 22-year-old running back for a professional North American football team was transferred to our trauma center by his team physician after being tackled during a game in July 2007. He complained of severe right upper thoracic pain. Physical examination was significant for swelling and tenderness over the right medial clavicle. Chest and clavicle x-rays were unremarkable, but the CT scan showed complete dislocation of the right SC joint with the medial clavicle mildly encroaching on the right subclavian vein (Fig. 1). Patient was brought urgently to the operating room for closed reduction of the SC joint under general anesthesia by cardiothoracic and orthopaedic surgery. He was placed in a supine position with a sandbag between the scapulae. In line traction was applied to the arm at 90 degrees of abduction, and a towel clip was used to gain control of the clavicle and guide reduction. A click was heard, and the intraoperative fluoroscopic Serendipity view confirmed reduction. Postoperatively, the patient was placed in a figure-of-eight bandage. At 4 weeks, he was not tender to palpation, had a full range of shoulder motion, and the SC joint was stable under posterior load. He started rehabilitation and was cleared to play football by team physicians at 10 weeks.

On his first game back, he complained of the same pain after a tackle. He was assessed, diagnosed, and stabilized at the field by the team physician and once again transferred to our trauma center. This time, he also complained of shortness of breath, but his oxygen saturation was 100% on room air. CT scan confirmed a recurrent posterior dislocation of his SC joint (Fig. 2).

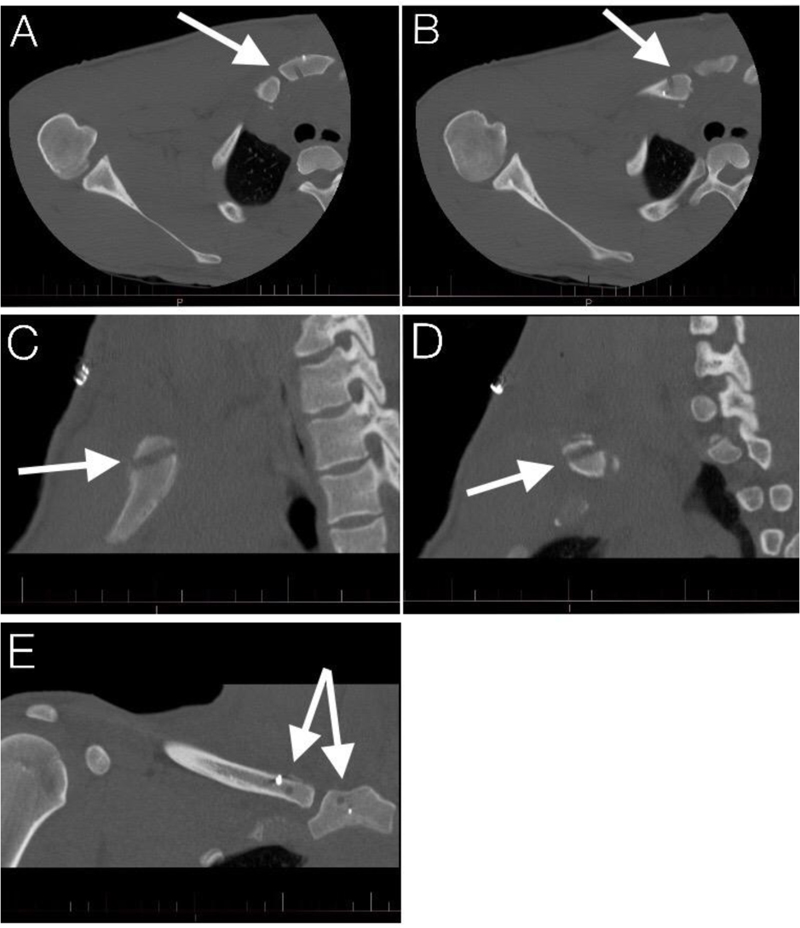

He was taken to the operating room for an attempt at a closed reduction with possible open reduction and SC joint reconstruction. A cardiothoracic surgeon was present in the operating room, and the patient’s arm and chest were sterilely prepped for the potential requirement of a sternotomy to address possible intrathoracic vascular compromise. The closed reduction did not maintain a stable joint, and therefore an open reduction was performed. A skin incision was made transversely over the clavicle and then curved longitudinally over the sternum in line with a potential sternotomy incision. Dissection was carried through subcutaneous tissue, platysma, and the trapezial and pectoral attachments to expose the medial end of the clavicle. The manubrium was dissected free from soft tissue to allow 1 finger behind the sternal notch. A 4.5mm hole was drilled into both the manubrium and clavicle from an anteroinferior to the posterosuperior direction (Fig. 3C-D) to minimize iatrogenic injury. This was drilled incrementally with a 2.0mm, 2.5mm, 3.5mm, and 4.5mm drill to minimize the force needed to drill and avoid plunging. A semitendinosus allograft was then cut to a 4.5mm diameter and passed through the drill holes in a figure-of-eight fashion similar to the method described by Castropil et al. [11] used to reconstruct an anteriorly dislocated SC joint in a Judo player. In addition, TwinFix FT suture anchors (Smith & Nephew, London, United Kingdom) were placed in the manubrium and clavicle to augment the reconstruction (Fig. 3A-E). Closure involved repairing the capsule and reattaching the pectoral and trapezial attachments. Postoperatively, he was immobilized for 6 weeks and then progressed with range of motion and strengthening exercises. He was counseled not to return to collision sports due to the potentially life threatening nature of his injury and the paucity of outcomes in this patient population in the literature. The patient requested a second opinion and was referred to another orthopaedic surgeon also experienced in the care of professional athletes, who then referred the patient to yet another colleague due to a lack of personal experience with this injury. After the patient’s SC joint was manually tested with approximately 90kg of posteriorly directed force, he was cleared to play football and subsequently returned to play professional football successfully the next season. He played 2 more seasons with no recurrence of pain or instability at this high-impact position before retiring for reasons unrelated to health or football.

3. DISCUSSION

Posterior SC joint dislocations are an extremely rare but serious injury representing only 0.03-0.05% of all traumatic joint dislocations [1, 2]. A third of the cases have had associated complications such as vascular compromise, pneumothorax, myocardial conduction abnormalities, brachial plexus compression, tracheal impingement, esophageal rupture, and fatal tracheoesophageal fistula [3, 9, 12-19]. A prompt diagnosis and reduction can reduce complications and improve the chances of a successful outcome [3, 4].

A high index of suspicion is needed to diagnose this injury. Motor vehicle collisions (40-47%), sports (21-31%), and falls are the most common causes of SC joint dislocations [9, 20]. Mechanism of injury can be by direct trauma to the SC joint or by indirect trauma to the shoulder, causing an axial load to the clavicle. If the acromion is posterior to the sternum (which is more often the case), then an anterior dislocation can occur and conversely, if the acromion is anterior to the sternum (such as in football tackling positions), then a posterior dislocation can occur [13, 21-23]. Clinical findings alone cannot always distinguish between anterior and posterior dislocations, and diagnosis is ultimately made by imaging [24]. Adequate x-rays are challenging because of superimposed structures and special views such as Hobbs, Heinig, or the Serendipity view attempt to overcome this challenge [7, 25-27]. Nonetheless, CT scan remains the gold standard to make the diagnosis and can also give information on vital adjacent structures and help differentiate a physeal fracture from a true dislocation for patients under the age of 25 [21, 28, 29].

Urgent reduction is necessary despite a lack of symptoms, and delays in reduction are associated with complications and failure to achieve reduction [6, 16, 30, 31]. There is controversy over whether to proceed with a closed or open reduction. Wirth notes in his review of the literature that the standard treatment has been an open reduction, however, since the 1950’s, the preference has been attempting a closed reduction first [20, 32, 33]. It has been argued as an excellent first line treatment because it is effective and conservative. However, while attempts at closed reduction are generally safe, it has a low success rate (50%) [3, 4, 29] and is not completely free of complications. Worman and Leagus had reported a posterior SC joint dislocation that was found during open reduction to have the clavicle impale the right pulmonary artery [16]. They noted had a closed reduction been attempted in the ED, the result could have been disastrous. In patients under the age of 25, a physeal fracture should be on the differential. CT scan fails to recognize this in half the cases [4]. Some authors point to the excellent osteogenic healing potential and bony remodeling as reasons for managing these injuries with a closed reduction [20, 23], however, Laffosse et al. cite 100% failure in attempts at closed reduction due to entrapped periosteum and advocate an open approach [4]. Open reduction and surgical stabilization is indicated when closed reduction fails or in recurrent instability. A variety of surgical procedures have been described including Steinmann pin fixation [20], Kirschner wire fixation (simple [34] and tension banding [35]), screw fixation [36], plate fixation with a variety of techniques (Ledge plating [37], Balser plate [38, 39], and locking plate [40-42]), external fixation [43], suturing with a variety of materials and techniques (synthetic [44, 45], transosseous sutures [46-49], and suture anchors [50]), reconstruction with different soft-tissue grafts (sternocleidomastoid [51-53], fascia lata [40], semitendinosus [52, 54, 55], subclavius [56], palmaris longus [57], and iliotibial band [57]), and medial clavicle resection with and without interpositional arthroplasty [52, 58]. Because of the rarity of surgical cases, prospective comparative studies do not exist and thus no treatment of choice has been established. The evidence that we have to direct our decision making is in previous case studies, biomechanical studies, and expert opinion.

The SC joint has the least amount of bony stability of all the major joints in the body, and its stability is predominantly based on its strong ligamentous attachments [20, 59-61]. Cadaveric sectioning experiments have shown that the posterior capsular ligaments are stronger than the anterior ligaments [62], and it has been cited that this is the reason why posterior dislocations are less common than anterior dislocations [59, 63]. However, clinically, in complete dislocations, both ligaments are likely torn, and the direction of force is more likely the determining factor. The SC joint is a diarthrodial joint, but behaves more like a ball and socket joint allowing movement in all planes, including rotation [2]. It is the only true articulation between the upper extremity and the axial skeleton and, therefore, is likely the most frequently moved joint in the body [58, 64]. Considerations in surgical stabilization should try to respect this anatomy. Therefore, hardware or rigid fixation across or through the joint is less than ideal. The risk of implant failure exists, and migration of pins with grave morbidity, including 7 deaths, has been reported [34, 65-73]. Early arthritis has been reported postoperatively [38]. Methods to stabilize the SC joint while preserving motion are preferred. The biomechanical study by Spencer and Kuhn has shown that figure-of-eight with a semitendinosus graft had the highest load to failure and stiffness when compared to two other techniques – intramedullary tendon and subclavius reconstructions [62]. Since this finding, more studies utilized the figure-of-eight graft reconstruction in treating sternoclavicular instability [29, 54, 55, 74-79].

In our patient, the surgeon (P.A.M.) reconstructed the sternoclavicular joint using a figure-of-eight with a semitendinosus allograft similar to the method described by Castropil [11], who successfully treated a chronically anterior dislocated SC joint in a high-level Judo player. The primary difference between this method and that in Spencer’s biomechanical study [62] is the use of one drill hole in the clavicle and sternum compared to two. While the technique using two drill holes is theoretically stronger, there is an increased risk of fracture ((Fig. 3) shows little space available to safely accommodate two 4.5mm drill holes) and iatrogenic injury compared to one drill hole. The reconstruction, in this case, was also augmented with suture anchors which have been reported to repair dislocated SC joint as the sole treatment [50], and the capsule was also repaired.

Posterior SC joint dislocation is seen particularly in association with American football [1], however, there is little information on outcomes and no definitive guidelines for return to high risk, contact sports. Laffosse et al. [4] published (after the time of injury of our patient) a relatively large case series (26 patients) of posterior SC joint dislocations in young workers and sports players with good to excellent results treated with closed or open reduction with a primary repair or a variety of surgical stabilization techniques. Eighteen of the 26 patients were able to resume their usual sports activities at the same level. All patients had a primary occupation other than their sport, so it appears that they were all recreational athletes. A more recent study of 18 patients, including recreational and professional sports players, showed high rates of survivorship (90%) and return-to-sports (94%) at a minimum 5-year follow-up of the surgical figure-of-eight reconstruction technique using hamstring autograft [80]. Although the study population consisted of those with preoperative SC joint instability resulting from anterior dislocation, the applied construct’s stability and potential in enabling a preinjury level of sports activity should be noted, especially in the dearth of studies monitoring postoperative return to sports after SC joint reconstruction.

Because of our patient’s occupation, that of a running back in professional North American football, his demands and the amount of stress that his SC joint will be subjected to are quite different than the average person. Moreover, we suspect the forces across the SC joint in a professional running back are much greater than the average weekend warrior or limited contact sports athlete. To our knowledge, there have been two cases of posterior SC joint dislocation reported in similar level athletes since the injury of our patient. A division I collegiate cornerback [81] and a professional league wide receiver [82] each underwent successful closed reductions, and the latter returned to football asymptomatically after 5 weeks. However, our patient had redislocated on his first game back after his initial treatment by closed reduction. Fortunately, there were no associated mediastinal injuries. In proceeding with open reduction and surgical stabilization, we found only one case report that was similar. Brinker [36] reported open reduction and rigid internal fixation with two 7.0mm cannulated screws to treat a posteriorly dislocated SC joint in a collegiate football player. The screws were removed 3 months postoperatively and screw holes were grafted with allograft bone. The patient returned to collegiate football approximately a year later. The advantages of our surgical method in reconstructing the SC joint with a soft tissue graft are that it involves only one surgical procedure, does not violate the joint with hardware, and motion is preserved. The literature supports the use of semitendinosus in a figure-of-eight as the strongest soft tissue construct.

CONCLUSION

Our patient returned to professional football as a running back and was symptom free from his SC joint reconstruction. We believe that this is an option that should be highly considered when managing a posterior dislocation in a high-level contact player. However, based on the paucity of literature and evidence on the topic, we still feel that players should be seriously counseled about the potential dangers associated with this injury and the unknown risk of recurrence. Therefore, discontinuation of participation in contact sports after this type of injury, even despite a clinically successful reconstruction, remains our ideal recommendation.

LIST OF ABBREVIATION

| SC | = Sternoclavicular |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

This study has been approved by the Research Ethics Board of McGill University Health Centre in Canada with the approval number 12-300 GEN.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No animals were involved for studies that are the basis of this research. All the humans used were in accordance with the Research Ethics Board of McGill University Health Centre in Canada and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 as revised in 2013.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

STANDARDS OF REPORTING

CARE guidelines were followed.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

Not applicable.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Yung Han is on the Editorial Advisory Board of The Open Orthopaedics Journal.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.