All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Tendon-Holding Capacities of Two Newly Designed Implants for Tendon Repair: An Experimental Study on the Flexor Digitorum Profundus Tendon of Sheep

Abstract

Background:

Two main factors determine the strength of tendon repair; the tensile strength of material and the gripping capacity of a suture configuration. Different repair techniques and suture materials were developed to increase the strength of repairs but none of techniques and suture materials seem to provide enough tensile strength with safety margins for early active mobilization. In order to overcome this problem tendon suturing implants are being developed. We designed two different suturing implants. The aim of this study was to measure tendon-holding capacities of these implants biomechanically and to compare them with frequently used suture techniques

Materials and Methods:

In this study we used 64 sheep flexor digitorum profundus tendons. Four study groups were formed and each group had 16 tendons. We applied model 1 and model 2 implant to the first 2 groups and Bunnell and locking-loop techniques to the 3rd and 4th groups respectively by using 5 Ticron sutures.

Results:

In 13 tendons in group 1 and 15 tendons in group 2 and in all tendons in group 3 and 4, implants and sutures pulled out of the tendon in longitudinal axis at the point of maximum load. The mean tensile strengths were the largest in group 1 and smallest in group 3.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, the new stainless steel tendon suturing implants applied from outside the tendons using steel wires enable a biomechanically stronger repair with less tendon trauma when compared to previously developed tendon repair implants and the traditional suturing techniques.

INTRODUCTION

After tendon repair, early mobilization is necessary in order to prevent loss of motion [1, 2]. Verdan suggested that passive mobilization at four weeks after tendon repair improved the results by tearing fresh adhesions in 1960 [3]. Ten years later, Kleinert et al. and Lister et al. reported the results of tendon repair with a bunnel suture technique followed by immediate active extension and passive flexion [2-4]. Later studies confirm those findings and it is now widely accepted that the repaired tendons should be mobilized early to prevent contractures.

In order to expose a repaired tendon tension force should be applied and the early repair should grant maximal strength. Two main factors determine the strength of tendon repair which are tensile strength of repair material andgripping capacity of suture configuration [5-7]. These two variables should be maximum for maximum strength.

Many studies were performed to demonstrate the tensile strengths of suture materials or tendon-holding capacities of different suture configurations [6, 8-10]. Different repair techniques and their modifications were developed to increase the strength of repairs. However, none of these techniques and suture materials seemed to provide enough tensile strength with large safety margins for early active mobilization [11, 12].

In order to overcome this problem tendon suturing implants are being developed. An implant applicable to a tendon should have an easy to apply design and is preferably economically advantageous. We designed two different suturing implants. The aim of this study was to measure the biomechanical characteristics of our newly designed implants and to compare them with commonly used suture techniques.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In this study, we used 64 flexor digitorum profundus tendons of fore extremities of sheep. The tendons were harvested in two hours after the sheep were slaughtered. After the paratenon was disected, a 15 cm piece of tendon was excised. The tendons were held in a wet gauze (isotonic 0.9% NaCl solution) during the 2 hour period in which the implants were applied to the tendon and the 3 hour period in which the measurements were taken.

There were four groups with 16 tendons in each group. We applied our newly designed model 1 and model 2 tendon holding implants to the first 2 groups respectively. Classical Bunnell and locking-loop techniques were applied to the 3rd and 4th groups respectively by using 5 Ticron sutures (Tyco, Waltham, MA) (Table 1).

Specialities of suture materials.

| Suture Material | Characteristics | Thickness |

|---|---|---|

| 5 Ticron | Synthetic, Nonabsorbable, Multiflament | Sutur material: 1 mm |

| Needle: 1.4 mm (most thickness part) | ||

| Stainless steel | Natural, Nonabsorbable, Monoflament | Stainless steel wire: 0.8 mm |

| Transverse pin: 0.6 mm |

Design of the Implants (Model 1 and Model 2)

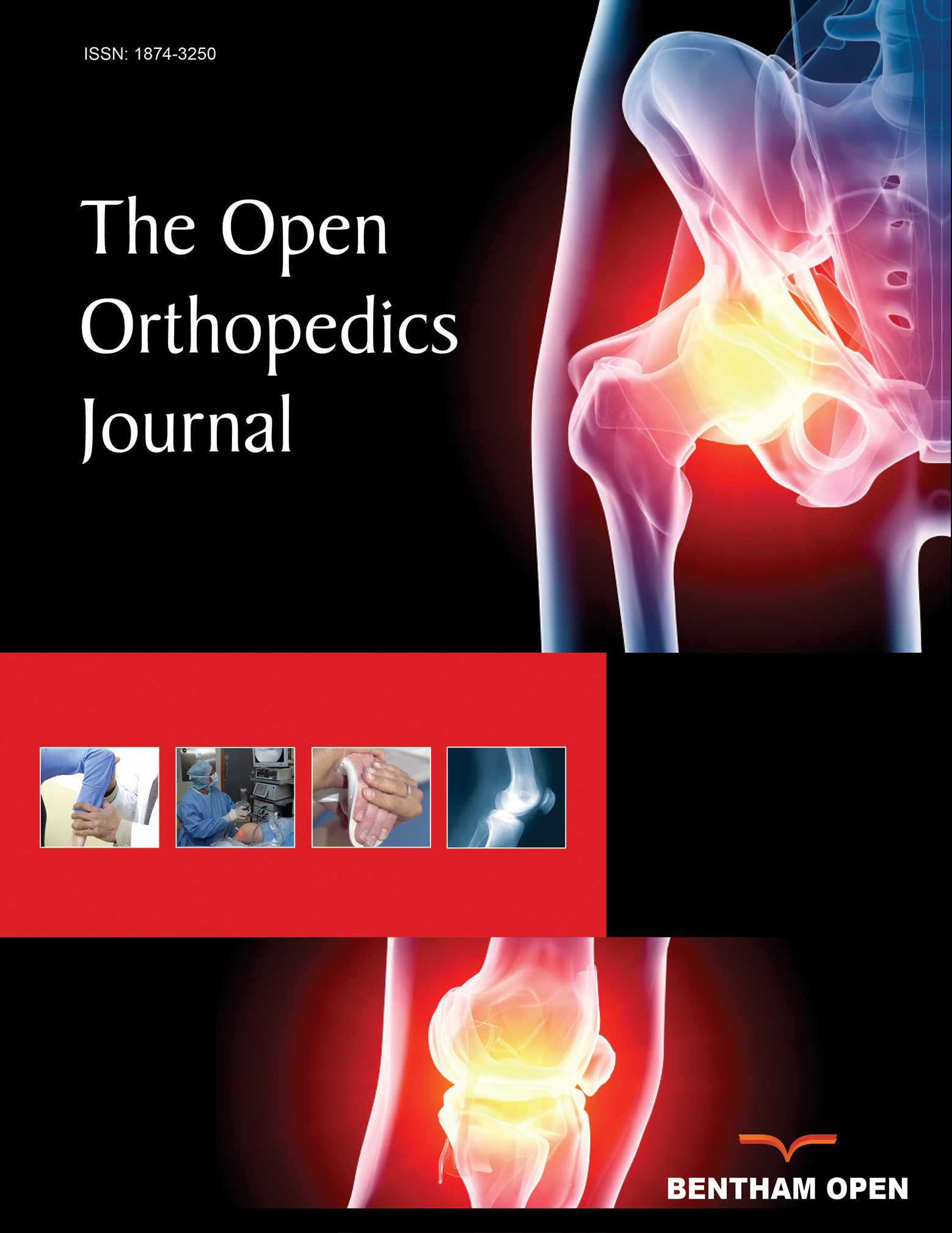

Two metal implants were produced by using a 0.8 mm stainless steel wire. Both implants had a loop like shape with 2 identical prongs. In model 1, on each prong, holes with 0.7 mm diameter were formed with 2.1mm intervals and in model 2, on each prong, holes with 0.7 mm diameter were formed with 7.7 mm intervals (Fig. 1).

Designing of holes in two implants.

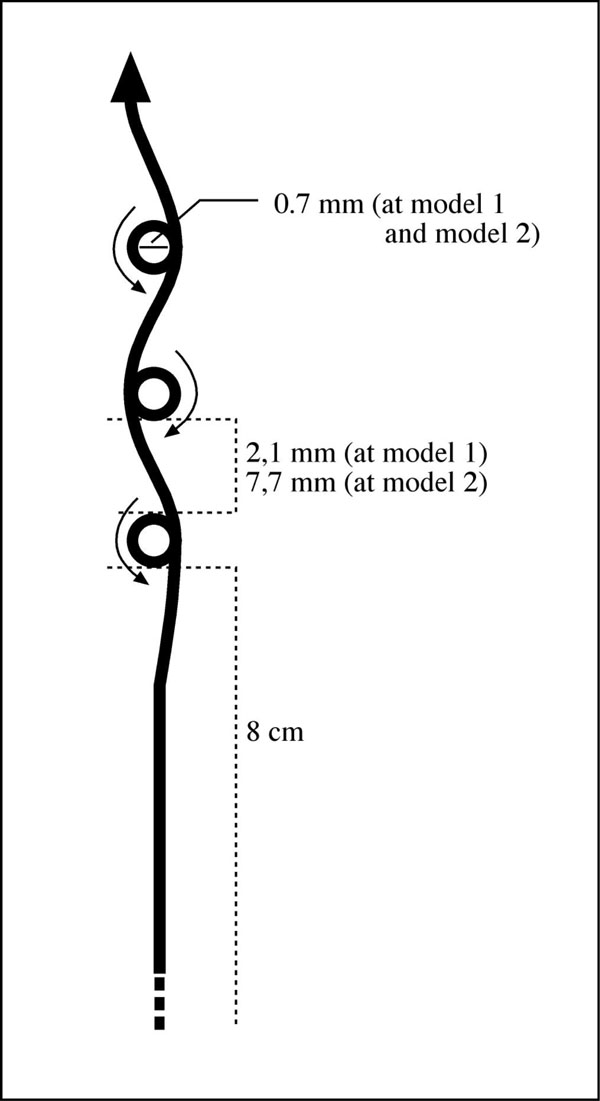

In both models approximately 5 mm after the last hole of one prong, wires were bended in a demilune manner and on the opposite prong, after 5 mm, the holes were placed exactly opposite, exact alignment and exact number (Fig. 2).

Model 1 and model 2.

Model 1 had 10 holes and model 2 had 5 holes at each side. Two ends of the wire (8 cm long) were twisted from 7.5 mm distal to the last hole to form the tail of the implant (Fig. 2). Model 1 was applied to group 1, model 2 was applied to group 2.

Tendon Repair Protocol and Biomechanical Testing

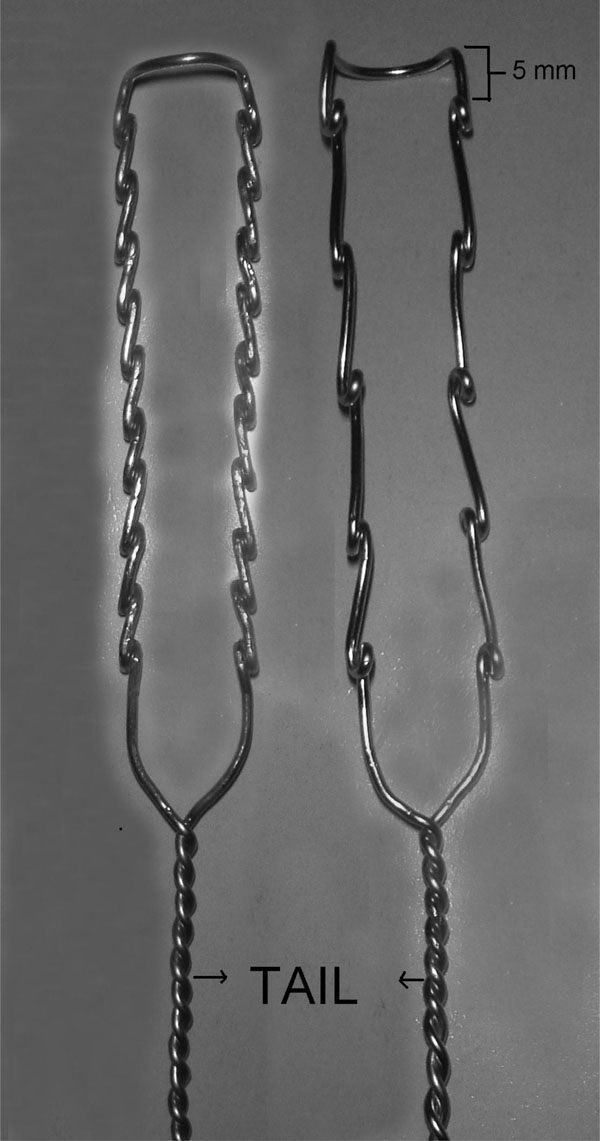

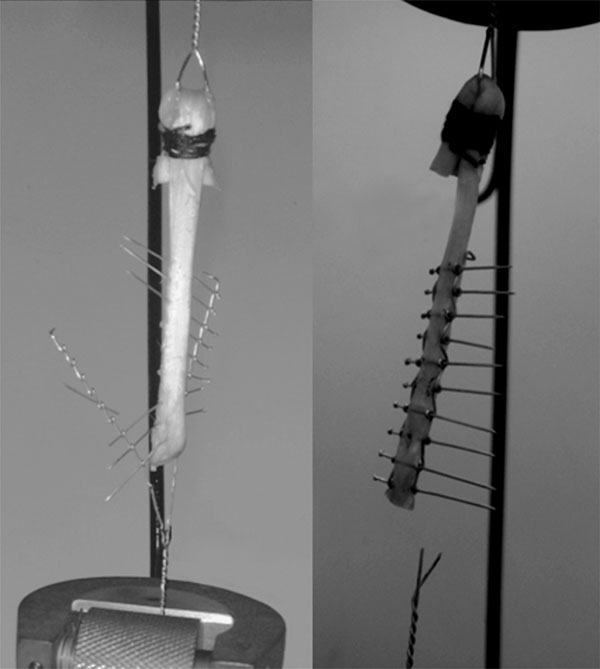

The proximal end of the tendon was passed through a wire loop and turned over and sutured to itself using polyglactin sutures (Fig. 3). The proximal nonimplanted part of tendon was holded by aid of that circle shaped wire.

Application of model 1 to tendon.

Models 1 and 2 were applied to 16 tendons in groups 1 and 2, respectively. Each tendon was first placed between the prongs of the implant. Then 0.6 mm stainless steel pins were sent through the holes. The pins were paralel to each other and were perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the tendon. Ten pins were used for fixation in model 1 and 5 pins in model 2. The most distal pin was placed 1cm above the distal end of the tendon (Fig. 3).

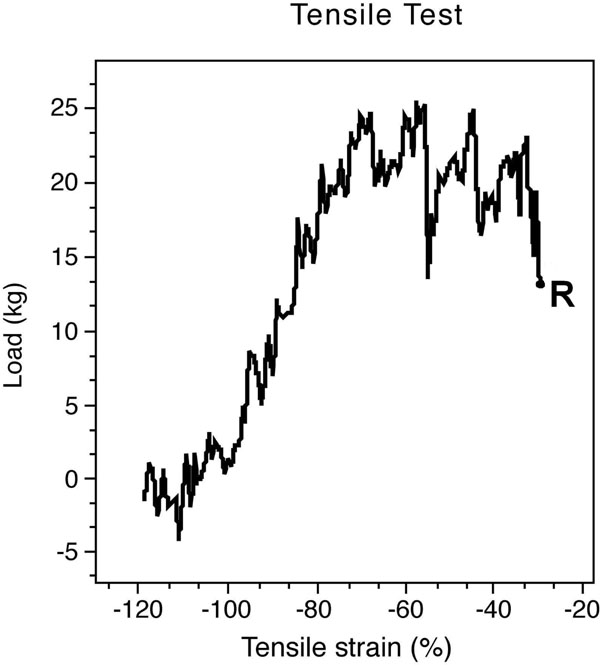

Biomechanical tests were performed with the Instron device (electrohydrolic model 1321B; Instron, Canton, MA). The proximal wire loop and the distal tail of each implant were attached to the Instron clamps of the test device. The testing machine was programmed to exert a 20-mm/sec tensile force. The repair construct was loaded to failure. The data were recorded automatically (Fig. 4).

Electronic output device indicates the maximum load that the implant squirms out of the tendon and the plateau of the maximum tensile strength after the squirming of the implant. (R- rupture point).

Statistical Tests

Kruskal-Wallis ( Nonparametric ANOVA) test was made with SSPE for statistical analysis. p<0.01 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

In group 1, implant failures were seen in 2 and transverse wire failure was seen in 1 tendon (one implant failed at the end of most distal hole and the other failed at the demilune part) (Fig. 5).

Failed model 1 implants.

No implant failure was observed in group 2. One implant in group 1 and one implant in group 2 was deformed during the test (Table 2).

Reasons of failure.

| Failure | Implant 1 | Implant 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Failure of transverse pin | 1 | - |

| Failure of implant | 2 | - |

| Pull out of implant | 13 | 15 |

| Deformation of implant | 1 | 1 |

These suture materials were eluded from the tendon longitudinally at the point of maximum load in group 3 and 4. On the other hand, 13 implants in group 1 and 15 implants in group 2 were eluded from the tendon.

Test results demonstrated that the tendon-holding capacity of model 1 is significantly higher than model 2 and other suture tecniques (p < 0.001). All results were shown in Table 3.

Maximum tensile strength of each implant.

| Number | Group 1 kg/F | Group 2 kg/F | Group 3 kg/F | Group 4 kg/F |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 41.77 | 22.00 | 16.53 | 21.7 |

| 2 | 26.5 | 26.99 | 17.87 | 22.42 |

| 3 | 42.70 | 25.24 | 22.34 | 23.81 |

| 4 | 37.40 | 23.92 | 21.82 | 20.16 |

| 5 | 25.65 | 22.28 | 19.37 | 18.28 |

| 6 | 28.69 | 18.26 | 18.47 | 21.17 |

| 7 | 27.89 | 25.46 | 20.52 | 18.24 |

| 8 | 29.60 | 17.78 | 19.58 | 22.2 |

| 9 | 29.1 | 18.5 | 21.61 | 23.6 |

| 10 | 30.18 | 27.88 | 20.13 | 21.43 |

| 11 | 32.72 | 31.13 | 17.49 | 19.24 |

| 12 | 26.18 | 25.18 | 16.2 | 25.72 |

| 13 | 31.21 | 36.00 | 20.7 | 21.5 |

| 14 | 32.42 | 24.30 | 19.34 | 24.3 |

| 15 | 34.10 | 24.81 | 25.32 | 26.32 |

| 16 | 26.2 | 25.99 | 22.5 | 18.4 |

| Mean | 31.39 (SD: 5.30) | 24.73 (SD: 4.68) | 19.98 (SD: 2.41) | 21.78 (SD: 2.53) |

DISCUSSION

In order to provide satisfactory clinical results after tendon repair, early mobilization should begin immeadiately [8, 13, 14]. Studies of Kleinert et al. and Lister et al. have shown that early protected mobilization after tendon repair improves results by decreased adhesions and increased range of motion [2, 4]. However early mobilization cannot be obtained due to unreliable tensile strength.

Tensile strength of a tendon repair is determined by two factors; which are tensile strength of repair material and gripping capacity of suture configuration. In literature, there are many studies about repair techniques and their tensile strengths [6, 8-10]. In a recent cadaver study, triple bundle and locking-loop (Krakow) techniques were compared and 6 stranded triple bundle technique was found to have a tendon-holding capacity 3 times of that of the locking-loop technique [9]. The authors concluded that this important difference was mostly due to the number of strands crossing the tendon body rather than complex configuration. In our study, the superiority of model 1 to model 2 supports this idea. The reason for this is the fact that there are 10 transverse pins on model 1 and 5 on model 2. In our opinion, the tendon holding capacity of the implants is linearly proportional to the number of pins.

Other determinant of the strength of a tendon repair is the suturing material. As in the above mentioned study, many techniques were used to obtain enough strength to begin early motion of the repaired tendon. However, none of them was successful as they failed to combine the ideal technique with the ideal suture material.

Strength of a repair at early stage of tendon healing is primarily dependent on characteristic of suture material. So suture material is more important determinant for early mobilization [10].

Trail et al. suggested that the ideal suture material should have high tensile strength, be inextensible and be easy to handle the knot [15]. Stainless steel was recommended because of its high tensile straight and non reactivity in past routinely. However, its use is discontinued due to kinking and handling diffuculties [8, 16]. If the elasticity of the suture material is high in any strength, the amount of the gap increases which interrupts or delays the healing. In this manner, the lower elasticity of stainless steel compared to other suture materials is an advantage in tendon repairs [6, 16-18]. Because of these advantages we used stainless steel as the suturing material in our study. In order to overcome the kinking and handling problem model 1 and model 2 implants were designed. Our study shows that both of the implants made of stainlees steel had superior results when compared to the classical suturing techniques with using 5 Ticron as the suture material.

There are few studies about tendon implants. Erol et al. develeoped a stainless steel implant in 2 different designs and applied them to the sheep achilles tendon and measured their tendon holding capacities [6]. Unlike our study, their implants were completely embedded into the tendons. They aimed to protect the gliding surface of the tendon but that causes an extra trauma to tendon body. In our study although the implants were applied to the outer surface of the tendon, the gliding surface of the tendon was left as implant free as possible.

Su et al. compared the the results of the patients treated by Teno Fix™ Tendon Repair System and four stranded cruciate suture for zone 2 flexor tendon ruptures in 85 fingers [19]. There were no reruptures in the tenofix group but 9 reruptures were seen in four stranded cruciate suture group. No difference was noted regarding range of motion, dash score pain, swelling between 2 groups but the ruptures in nine patients treated with the traditional suturing techniques were found to be statistically significant (p<0,01). In this study, the metal implants were found superior to the traditional suturing materials. But as in the study of Erol et al. the implant was embedded in the tendon which causes another trauma to the already injured tendon.

In our study the thickness of the transverse wire was 0.6 mm and the thickness of the wire was 0.8 mm which was used for the production of model 1 and model 2. Both models are narrower than the 5 Ticron sutures used in group 3 and 4 where the suture diameter is 1 mm. Also the needle of the 5 Ticron suture has a 1.4 mm diameter. It is clear that thicker needle causes more trauma than transvers pin.

Transverse pins like in our study are impossible for clinical use. This is a limitation for our study. However we studied the strength of new design materials (model 1 and model 2) not transverse pins. 0.5 mm cerclage wire in same strength can be used instead of transeverse pins. Another limitation is that our implants are imposible for use in hand surgery. Our implants are suitable for gross tendons like aschilles. However, if we obtain clinical success with this implants in gross tendon surgery, new implants in same figures can be manufactured for hand surgery.

In conclusion, the new stainless steel tendon suturing implants applied from outside the tendons using steel wires enable a biomechanically stronger repair with less tendon trauma when compared to previously developed tendon repair implants and the traditional suturing techniques. However, these claims should be further tested by animal studies.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.