All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Possibility of Meniscal Repair for Degenerative and Horizontal Tears

Abstract

Background:

Poor long-term clinical results have been reported following partial and total menisectomy. To preserve the meniscus, many surgeons perform meniscal repairs when possible. However, meniscal repair for degenerative tears and white-white tears is challenging.

Methods:

15 patients underwent meniscal repair for degenerative and horizontal tears. Follow-up evaluation included clinical assessment and Magnetic Resonance Imaging examination. The mean follow-up time was 11.9 months (from 8 months to 13 months).

Result:

The healing rate on clinical assessment was 86.6% 12 months after surgery. MRI showed partial healing in 12 patients, complete healing in 1 and no healing in 2 after 12 months.

Conclusion:

The findings suggest that it may be possible to repair degenerative and horizontal meniscal tears.

1. INTRODUCTION

The meniscus does not regenerate once it has been removed because of trauma; secondary osteoarthritic changes occur due to the loss of meniscal function, including alterations in load distribution, impact absorption, and articular sliding and stabilization. To preserve the meniscus, many surgeons perform meniscal repairs for red-red tears and red-white tears when possible. However, meniscal repair for degenerative tears and white-white tears is challenging [1-3]. Previously, we reported that in the ruptured fragments of trauma-injured menisci, collagen types II and III disappear first, followed by collagen type I, resulting in the abrogation of fiber construction. It is assumed that these functions are lost because insufficient nutrition is supplied to the meniscal cells in the ruptured fragments. Meniscal function of the rupture fragment cannot be maintained as most meniscal cells have disappeared; any remaining meniscal cells produce only low levels of collagen types II and III. It may be possible to repair degenerative and horizontal tears if meniscal cells remain in the ruptured fragment of the meniscus. The regenerated meniscus may lead to the dilapidation if it does not function normally [4]. It is important to observe changes in MRI findings after meniscal repair for degenerative and horizontal tears in order to assess the repair and to enable the development of a treatment strategy that aids the histological and functional regeneration of the meniscus. Therefore, we performed postoperative clinical assessment and MRI examination following meniscal repair for degenerative and horizontal meniscal tears.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Forty-three patients underwent arthroscopic meniscal repairs between June 2015 and November 2017 at our institute. We selected for evaluation 15 patients who underwent meniscal repair for degenerative and horizontal tears. We excluded 28 patients with ACL reconstruction or meniscal suture in meniscal repairs for red-red tears and red-white tears (from 11 to 74 years old). The group was composed of 10 males and 5 females, whose mean age at surgery was 40.5± 11.8 years (from 27 to 70 years old). 8 had medial tears and 7 had lateral. The time between the appearance of symptoms and the operation ranged from 1 month to 12 months. The mean follow-up time was 11.9 months (from 8 months to 13 months) (Table 1). The hip-to-ankle standing x-ray image demonstrated the anatomical lateral distal femoral angle (FTA) was 174.9±1.2°.

| Characteristic | value |

|---|---|

| Mean age | 40.5± 11.8 |

| Gender (male/female) | 8/7 |

| Side, right/left | 10/5 |

| Side, medial/lateral | 8/7 |

| Duration of symptom, month | 5.6± 5.9, (1-24) |

| Follow-up time, month | 11.9± 1.2 |

2.1. Meniscal Repair

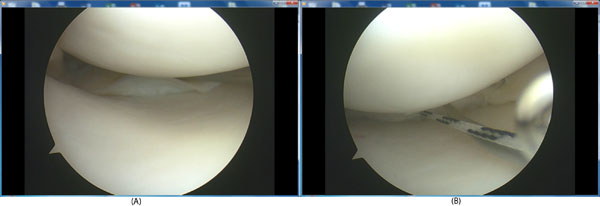

All tears were horizontal and degenerative, and located in the white zone to red zone. In our study, all tears were located at the posterior horn or body, or spanned more than one part (from anterior horn to body, or from body to posterior horn) (Table 2). In all cases, the inside-out technique was used, employing non-absorbable material or Fast-Fix system (Fig. 1A, B). No kind of meniscal stimulation, such as fibrin clot or avascular access channels, was used in these cases.

2.2. Clinical Assessment

Clinical evaluations were performed using the Lysholm score and Subjective International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) 2000 before and after surgery. According to Barrett’s criteria, an unhealed meniscus was defined by symptoms or physical signs, such as a swelling, joint-line tenderness, locking or blocking, or a positive McMurray test. Radiological evaluations were performed using MRI examination at 6 months and 12 months after surgery.

| Factors | value |

|---|---|

| Injury pattern | - |

| Horizontal | 7 |

| + Radial | 2 |

| + Longitudinal | 6 |

| Anatomic location | - |

| Posterior horn | 6 |

| Body | 1 |

| 2 parts | 9 |

2.3. MRI Technique

All MRIs were taken on a 1.5 T system (Signa, General Electric Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI), using a dedicated send-receive extremity coil (General Electric). Sagittal images were obtained with a 16-cm field of view, 3 mm slice thickness with no interslice gap, frequency-selective fat suppression, and a matrix of 256x192 at 2 excitations. Images were obtained with a proton-density weighted fast spin-echo technique (repetition time TR/effective echo time TEef, 4000-5500/17-40 ms, bandwidth, 16-20.8 kHz). Coronal images were obtained without the use of frequency-selective fat suppression but with a higher resolution technique, using a 13-cm field of view, 4-mm slice thickness with no interslice gap, and a matrix of 256x256 or 512x256 at 2 excitations. Pulse sequence parameters included TR/TEef, 3500-4500/21-34 ms. All fast spin-echo sequences were obtained with an echo train of 6-8.

All MRI studies were interpreted by an experienced musculoskeletal radiologist (HP). The images were scored using previously described meniscal repair criteria: signal intensity, morphological characteristics, and repair [5].

Statistical analysis was performed using R2.8.1. The Mann-Whitney U test was used for comparison procedure.

A. A horizontal tear in the medial meniscus in the white zone to red zone. B. Meniscal sure with non-absorbable material.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Clinical Assessment

The patients’ mean preoperative Lysholm score was 58.6 ± 12.7 (range: 31-72). The mean postoperative score was 87.2 ± 7.8 (range: 73-95) at 6 months after surgery and 93.8 ± 6.6 (range: 78-100) at 12 months after surgery. The patients’ mean preoperative IKDC score was 36.2 ± 11.8 (range: 17.2-50.1). The mean postoperative score was 65.4 ± 11.6 (range: 50.6-86.2) at 6 months after surgery and 74.3 ±10.4 (range: 54-91) at 12 months after surgery (Table 3). Using Barrett’s criteria [6], one case showed physical signs and was diagnosed as an unhealed meniscus. One patient had joint line tenderness (Table 4). The healing rate upon clinical assessment 12 months after surgery was 86.7%. Using the Lysholm score, there was no significant difference between 6-month and 12-month scores with respect to the injured side or patient age.

| Factors | 6M after op. | 1 Y after op |

|---|---|---|

| Extrusion | - | - |

| Sagittal 1/3~2/3 | 1 | 1 |

| Coronal 1/3~2/3 | 2 | 2 |

| 1/3 > | 2 | 3 |

| Signal | - | - |

| Increased in < 1/3 meniscus | 2 | 7 |

| 7;1/3 | 8 | 6 |

| Diffusely increased | 5 | 2 |

| Repair | - | - |

| Healed | - | 1 |

| Partly healed | 8 | 12 |

| No healing | 7 | 2 |

3.2. MRI Evaluation

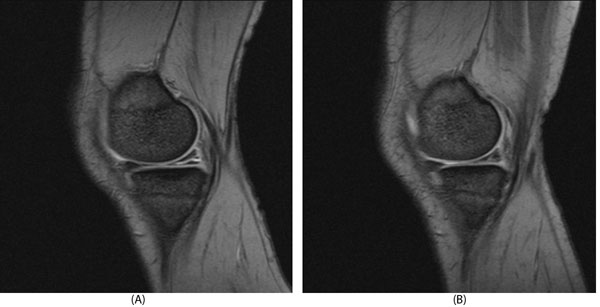

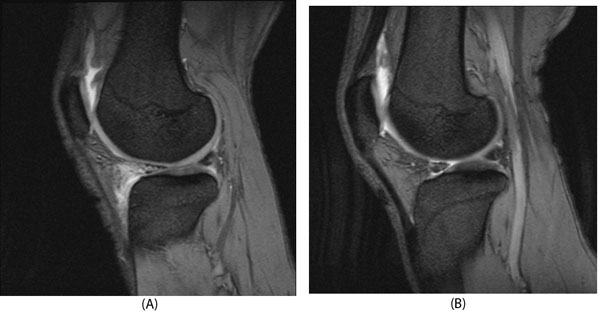

Six months after surgery, MRI showed partial healing in 8 patients and no healing in 7. After 12 months, MRI showed partial healing in 12 patients (Fig. 2A, B), complete healing in 1 (Fig. 3A, B) and no healing in 2 (Fig. 4A, B). Extrusion was noted in 1 patient in sagittal plane images and in 5 patients in coronal plane images 12 months after surgery (Table 5). An improvement in signal intensity was observed in 9 patients after surgery.

| Characteristic | Preoperative | Postoperative 6M | 1Y |

| swelling | 8 | 4 | 1 |

| Joint line tenderness | 12 | 1 | 1 |

| Locking | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Positive McMurray test | 15 | 0 | 0 |

4. DISCUSSION

The meniscus is a fibrocartilage structure containing an abundant extracellular matrix. Collagen type I is the most common type of collagen found in the meniscus, but the meniscus also contains collagen types II and III, and acid mucopolysaccharides. There have been many morphological and histochemical studies of menisci [7-14]. It includes the vascular area, which lies within 3-5 mm of the peripheral rim. The meniscal area can be classified into three zones: the red-red zone, the red-white zone, and the white-white zone.

In the treatment of meniscal injury, surgeons are aware of the influence of meniscectomy on knee articular cartilage dysfunction. Poor long-term clinical results have been reported following partial and total meniscectomy [8, 11, 15]. To preserve the meniscus, many surgeons perform meniscal repairs for red-red tears and red-white tears when possible. However, meniscal repair for degenerative tears and white-white tears is challenging [9, 16, 17].

| Factors | 6M after op. | 1 Y after op |

|---|---|---|

| Extrusion | ||

| Sagittal 1/3~2/3 | 1 | 1 |

| Coronal 1/3~2/3 | 3 | 3 |

| 1/3 > | 1 | 2 |

| Signal | ||

| Increased in < 1/3 meniscus | 4 | |

| 1/3 | 10 | 9 |

| Diffusely increased | 5 | 2 |

| Repair | ||

| Healed | 1 | |

| Partly healed | 8 | 12 |

| No healing | 7 | 2 |

Previously, we reported that in the ruptured fragments of trauma-injured menisci, these functions may be lost because insufficient nutrition is supplied to the meniscal cells in the ruptured fragments. If a tear occurs in the peripheral vascular area, collagen types I, II, and III are produced by the remaining meniscal cells or undifferentiated mesenchymal cells, possibly resulting in the full recovery of meniscal function. If a tear occurs in the avascular portion, however, no collagen is produced by undifferentiated mesenchymal cells. Meniscal function of the rupture fragment cannot be maintained as most meniscal cells have disappeared. This is considered to be the cause of the poor outcomes following meniscal suturing [4].

It is generally considered to be the case that damage to the inner, nonvascularized portion of the meniscus will not heal; in such cases, partial meniscectomy is typically performed. In this study, however, we performed meniscal repair for degenerative and horizontal meniscal tears. The meniscal tears in this study are horizontal and degenerative tears in the inner to outer portion of the meniscus. Prior to this study, we thought that it might be possible to perform meniscal repair on horizontal and degenerative tears in the red-white and red-red zones, but that tears in the white-white zone may not be amenable to meniscal repair. Our results, however, showed that the healing rate of clinical assessment 12 months after surgery was 86.7%. MRI showed partial healing in 12 patients, complete healing in 1, and no healing in 2 after 12 months. From these results, we consider that it may be possible to repair degenerative horizontal meniscal tears in many cases.

Two factors positively influenced the results in this study. The menisci are wedge-shaped semilunar tissues. The wedge-shaped cross-section of the menisci means that they can stabilize the femoral condyle as it articulates against the tibial plateau, by increasing congruence between the two surfaces. It is important to recover the original wedge shape by meniscal suturing in degenerative and horizontal meniscal tears. The abnormal movement in the meniscus inside may be eliminated by meniscal suturing in degenerative and horizontal meniscal tears. For inner meniscal injuries, Arnoczky and McAndrews reported that some reorganization of the matrix may take place due to changes in the mechanical environment, but that a healing response is absent [18, 19]. By eliminating abnormal movement in the meniscus, some reorganization of the matrix may occur due to changes in the mechanical environment, and it may be possible to repair degenerative and horizontal meniscal tears in many cases.

A. A 27 year-old patient with medial horizontal meniscal tear before meniscal repair. B. 1 year after meniscal repair.

5. LIMITATIONS

There were some limitations to our study. The small number of patients weakens the statistical power of the results. Further investigation with a larger sample size is needed to obtain more clinical data. In addition, follow-up arthroscopy was not performed. Despite these limitations, the present study contributes to our current understanding of the possibility of meniscal repair for degenerative and horizontal tears.

CONCLUSION

The healing rate of clinical assessment was 86.7% 12 months after meniscal repair for degenerative tears and horizontal meniscal tears. MRI showed partial healing in 12 patients, complete healing in 1 and no healing in 2 after 12 months. The findings suggest that it may be possible to repair degenerative and horizontal meniscal tears in many cases.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| MRI | = Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| IKDC | = International Knee Documentation Committee |

AUTHOR’S CONTRIBUTION

TM designed the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. KI, HK, RK and YT collected the data and participated in the design of the study. TU analyzed the data, and helped write. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

This study was approved by Ethical Review Boards of Kanmon Medical Center (Shimonoseki, Japan).

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No Animals were used in this research. All human research procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the committee responsible for human experimentation (institutional and national), and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Informed consent was obtained from each participant/patient.

FUNDING

This research was supported by the commissioned research expenses to Kanmon Medical Center (Shimonoseki, Japan) from Kyocera Japan, Japan Medical Dynamic Marketig ING, and Senko Medical Instrument Mfg. Co.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.