All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Elastic Changes of the Coracohumeral Ligament Evaluated with Shear Wave Elastography

Abstract

Background:

Although the shoulder range of motion significantly decreases with advancing age, how the natural aging process affects the joint capsule, including the Coracohumeral Ligament (CHL), in healthy subjects is still unknown.

Objective

To use shear wave elastography to investigate the correlations between age, sex, and shoulder dominance, and elasticity of the CHL in healthy individuals.

Methods:

Eighty-four healthy volunteers (mean age: 42.6; 39 men) were included in this study. They were divided into five groups based on age: 20s (20–29, n = 19), 30s (30–39, n = 17), 40s (40–49, n = 20), 50s (50–59, n = 13), and 60s (60–69, n = 15) groups. The elasticity of the CHL in the bilateral shoulders was evaluated at the neutral and 30° external rotation (ER at 30°) positions with the arm at the side while laying supine.

Results:

The elastic modulus was significantly greater in ER at 30° than in the neutral position regardless of sex or shoulder dominance (P < 0.001). Significant positive correlations between age and elasticity of the CHL were observed in both the neutral and ER at 30° positions regardless of shoulder dominance. Elasticity of the CHL was significantly greater with increasing age in both the neutral and ER at 30° positions on the dominant (P = 0.0022, P < 0.001, respectively) and non-dominant sides (P = 0.0199, 0.0014).

Conclusion:

The elasticity of the CHL increased with age, and the ER at 30° position could demonstrate faint changes in CHL elasticity.

Level of Evidence:

Level 3 Case-control study.

1. INTRODUCTION

Measurement of Range of Motion (ROM) is an important method of evaluating shoulder impairment, making a diagnosis, and planning effective treatments. Frozen shoulder is a common shoulder condition characterized by severe pain and global restrictions in ROM. Its etiology remains unclear, but the primary pathologies are assumed to affect the joint capsule including the Rotator Interval (RI) and the Coracohumeral Ligament (CHL) [1-3]. Although shoulder ROM significantly decreases with advancing age [4, 5], how the natural aging process affects the joint capsule, including the CHL, in healthy subjects is still unknown.

The CHL runs between the lateral base of the coracoid process and the greater and lesser tuberosities of the humerus. It covers the RI, and the supraspinatus (SSP) and subscapularis (SSc) tendons, anchoring itself to the coracoid process, which functions as the supporting structure for both the SSP and SSc tendons [6-8]. The thickness of the CHL is significantly related to ROM restriction in External Rotation (ER) [3, 9] as well as Internal Rotation (IR) [10, 11]. Even in patients with recurrent anterior glenohumeral instability, these changes are confirmed to be a part of the natural aging process [12]. Thickening of the CHL influences multidirectional ROM restrictions and could be an indicator of certain shoulder diseases.

Ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging have been used to evaluate and diagnose various shoulder impairments, such as rotator cuff tears [13]. However, alterations in the material properties of muscles and tendons cannot be assessed properly using those radiographic modalities. Recently, Shear Wave Elastography (SWE) was developed as a new, non-invasive, ultrasound imaging technique that provides both qualitative and quantitative information. It uses a focused ultrasonic pulse to evaluate real-time elasticity of the soft tissues based on viscoelastic properties [14]. The system propagates generated shear waves into the tissues and assesses their elastic modulus [15]. It is useful for evaluating the elasticity of soft tissues such as the Achilles tendon [16] and can facilitate rotator cuff injuries [17]. Furthermore, a recent study indicated that CHL in a frozen shoulder is stiffer than the CHL of the unaffected side based on an evaluation using SWE [12]. However, there have been no reports about the changes in elasticity of the CHL resulting from the natural aging process. We hypothesized that the elasticity of the CHL on the dominant side increases with increasing age because it operates under more stressful and impaired conditions in contrast to the opposite side.

The purpose of this study was to use SWE to investigate the correlations between age, sex, and shoulder dominance, and elasticity of the CHL in healthy individuals.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The study protocols were approved by the institutional review board of the Iwate Prefectural Central Hospital (approved number: 2455). All study participants provided informed consent. Eighty-four healthy volunteers (39 men and 45 women) were included in this study. All the volunteers selected were Japanese nationals having a BMI that is normal for the Japanese population. The mean age was 42.6 years (range: 22–69, Standard Deviation (SD): 13.6), and they were divided into five age groups: 20s (20–29, n = 19), 30s (30–39, n = 17), 40s (40–49, n = 20), 50s (50–59, n = 13), and 60s (60–69, n = 15). The elasticity of the CHL in the bilateral shoulders in the neutral position, as well as the 30° ER positions (ER at 30°), was evaluated using SWE (Supersonic Imagine, Aix-En-Provence, France) equipped with a 4-15 MHz superficial linear transducer. We excluded patients with a history of fractures around the shoulder girdle, previous shoulder and chest operations, and rotator cuff tears confirmed by ultrasound, and individuals with diabetes mellitus.

2.2. Measuring Elasticity of the CHL

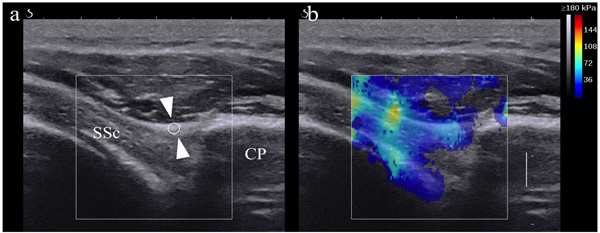

Two orthopedic surgeons with 11 and 13 years of musculoskeletal ultrasonographic experience, who had no access to each participant’s information, recorded the ultrasonic data used to determine CHL elasticity. The participants were placed in the supine position on an examination table to facilitate accurate measurements. Assistant physiotherapists maintained the elbows at 90° flexion with the arm at the side, and sequentially moved it from the neutral position to the 30° ER position. B-mode ultrasound was emitted in an axial oblique plane by placing the transducer over the lateral portion of the coracoid process, which revealed a longitudinal image of the CHL on the surface of the SSC [12]. For the SWE examinations, the participants’ postures and the transducer positions were the same as for the B-mode ultrasound measurements. The tip of the transducer was covered with gel and placed smoothly on the skin without exerting pressure on the tissues. Because chest wall motion could interfere with elastogram stability, all the participants were advised to hold their breath for 5–10 seconds during the assessments. CHL elasticity on the surface of the SSC was measured and recorded in both neutral and 30° ER positions Fig. (1b). A region of interest with a diameter of 1.5 mm was set at the centermost point of the coracoid process and at the primary attachment point of the SSC as the primary measurement area Fig. (1a) based on a previous report [12]. The circular regions of interest for the quantitative analysis provided the maximum, minimum, standard deviation, and mean elastic modulus in kPa. All kPa moduli were calculated from the raw data image using Osirix MD 9.5 medical imaging software. The mean elastic modulus for both shoulders was recorded for all participants in both positions. All measurements were obtained in triplicate by each of the two orthopedic surgeons and the average values were used for the statistical analysis. Ultrasonic penetration was estimated to be about 1.0 cm depending on the subject’s amount of body fat.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis for the two positions (according to sex, age, and dominance) was performed using the Student’s t-test and Wilcoxon’s rank sum test (elastic modulus of the CHL). All continuous variables were tested for deviations from the normal distribution. Correlations between continuous variables with and without normal distributions were analyzed using Spearman’s correlation coefficient. Differences among age groups were compared using the Kruskal-Wallis test (two-tailed). Data (age and CHL elastic modulus) were expressed as mean ± SD. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. To achieve a power of 80%, a level of 0.05 for statistical significance, and an effect size of 0.8, the sample size for each group needed to be 13. All statistical analyses were calculated using the statistical software package SPSS (version 23.0, Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). The Interclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) was calculated to determine the intra- and inter-rater reliability of measurements of the CHL elastic modulus, both in the neutral and 30° ER positions. Agreement was classified as poor (ICC, 0.00–0.20), fair (ICC, 0.20–0.40), good (ICC, 0.40–0.75), and excellent (ICC > 0.75).

3. RESULTS

Inter-observer reliability of elastic modulus measurements in the CHL was excellent in both the neutral position (dominant; interclass correlation coefficients [ICC]: 0.876, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.737–0.934, non-dominant; ICC: 0.865, 95% CI: 0.713–0.928) and ER at 30° position (dominant; ICC: 0.85, 95% CI: 0.559–0.932, non-dominant; ICC: 0.877, 95% CI: 0.664–0.942). The intra-observer reliability of elastic modulus measurements in the CHL was excellent in both the neutral position (dominant; ICC: 0.834, 95% CI: 0.773–0.883, non-dominant; ICC: 0.807, 95% CI: 0.737–0.863) and ER at 30° position (dominant; ICC: 0.773, 95% CI: 0.694–0.838, non-dominant: ICC: 0.803, 95% CI: 0.732–0.860).

There was no significant difference in the average ages of the men (43.9 years, SD 14.3) and the women (42 years, SD 13, P = 0.55). A comparison of the elasticity of the CHL between the neutral position and ER at 30° (n = 84) is shown in Table 1. The elastic modulus was significantly greater in the ER at 30° position than in the neutral position regardless of sex and shoulder dominance Table 1. There was no significant difference in the elasticity of the CHL between men and women for both the neutral and ER at 30° positions (P = 0.129 and 0.209, respectively). There was no significant difference in the elasticity of the CHL between the dominant and the non-dominant sides in both the neutral and ER at 30° positions (P = 0.824 and 0.386, respectively).

| - | Neutral | ER at 30° | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHL elastic modulus (kpa) | - | - | - |

| Men (n = 39) | 77.7 (36.5) | 105.8 (54.2) | <0.001 |

| Women (n = 45) | 65 (39.2) | 91.9 (46.4) | <0.001 |

| Dominant | 70.9 (38.3) | 98.3 (50.3) | <0.001 |

| Non-Dominant | 73.6 (42.2) | 103.7 (48.1) | <0.001 |

Correlation coefficients for age and elasticity of the CHL on the dominant and non-dominant sides are shown in Table 2. Significant positive correlations between age and elasticity of the CHL were observed in both the neutral and ER at 30° positions, regardless of dominance. The elasticity of the CHL at the 30° ER position was strongly correlated with the neutral position on the dominant side Table 2.

| - | Dominant (84) | Non-Dominant (84) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | R | P | R | P |

| Age/CHL elasticity | - | - | - | - |

| Neutral | 0.37 | <0.001 | 0.33 | 0.0023 |

| ER at 30° | 0.53 | <0.001 | 0.38 | <0.001 |

Graded color images of the elastic modulus in the CHL at the ER 30° position are shown in Fig. (2). The elastic modulus of the older group was higher (red) than that of the younger group (blue) Fig. (2d) when compared to the data in the younger age groups (blue color) Fig. (2b) in both neutral and ER positions.

Elasticity of the CHL in the different age groups is shown in Table 3. CHL elasticity was significantly greater with older age in both the neutral and the ER at 30° positions on the dominant side. CHL elasticity increased with increasing age and was at its highest value in patients over the age of 50. The non-dominant side showed similar changes compared to the dominant side. In the 30s and 40s age groups, the elasticity in the neutral position was equivalent irrespective of side dominance. However, CHL elasticity in the non-dominant side was greater in the ER at 30° position Table 3.

|

20s (n =19) |

30s (n =17) |

40s (n =20) |

50s (n =13) |

60s (n =15) |

P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dominant | Neutral | 45.1 (26.1) | 69.5 (33.2) | 73.7 (36.9) | 97.7 (44.5) | 78.4.(37.1) | 0.0022 |

| ER at 30° | 62.4 (29.4) | 81.5 (33) | 97.2 (44.5) | 131.6 (39.5) | 135.5 (63.5) | <0.001 | |

| Non-Dominant | Neutral | 52.5 (31) | 66.1 (42.2) | 73.1 (36.6) | 96.2 (50) | 89.9 (43.5) | 0.0199 |

| ER at 30° | 68.3 (29.8) | 105.5 (45.2) | 104.5 (41) | 128.6 (56.3) | 124 (50.4) | 0.0014 |

4. DISCUSSION

The most important finding of this study was that CHL elasticity increased with increasing age in healthy individuals. CHL elasticity at the 30° ER position was larger and more strongly correlated to the elastic modulus than CHL elasticity at the neutral position.

To date, there are no available data obtained using SWE regarding the relationships between CHL elasticity, age, sex, and side dominance in healthy adult subjects.

Naturally, shoulder ROM decreases with increasing age [18]. It is also affected by poor posture, as in the increased thoracic kyphosis with a forward head position and slouched trunk posture [19, 20]. Causes of joint stiffness can be classified as follows: arthrogenic (bone, cartilage, synovial membrane, capsule, and ligaments) and myogenic (muscle, tendon, and fascia) [21]. Among the intra-articular causes, the condition of the joint capsule is the main factor [22] and a thickened CHL is one of the most characteristic findings of frozen shoulder [1]. However, the manner in which degenerative changes affect shoulder motion in healthy subjects remains unknown.

The CHL originates from the horizontal limb of the coracoid process and covers the RI [23], extending coverage to the SSP, the infraspinatus, and the SSc muscles and their direct insertions [6]. The superficial layer of the anterior CHL continues smoothly to the SSc fascia, where it firmly covers an extensive area of the anterior surface of the SSc muscle (6). The CHL was thought to play an important role in the function of the RI [24]. Biomechanical studies have indicated that tension in the CHL has a significant effect on stability and ROM, providing resistance to the inferior and posterior translations of the humeral head [23, 25, 26]. Boardman et al. reported that the CHL had a more significant effect on increased stiffness and load failure than the superior glenohumeral ligament [25], which suggests that the CHL is more important for glenohumeral joint stability than the RI.

Arm position significantly influences the elasticity of the CHL. Wu reported that the elastic modulus of the CHL in symptomatic shoulders was not significantly greater than that of unaffected shoulders in the maximal ER position [12]. It is normal that the CHL tightens from the neutral to ER positions. However, after reaching the maximum ER position, it is difficult to evaluate the CHL elastic modulus appropriately. Therefore, we chose to evaluate the 30° ER position, which represents only half of the standard ER angulation. The elastic modulus in the 30° ER position was found to be increased, and its correlation coefficient tended to be greater when compared to that of the neutral position in this study. These results indicate that the CHL elastic modulus in the 30° ER position reflects faint changes in the CHL that could not be detected in the neutral position. The elastic modulus of the non-dominant side was greater than that of the dominant side in the ER at 30° position in the 30s and 40s age range groups, which suggests that age-related changes tend to occur early on the non-dominant side depending on usage frequency.

A thickened CHL is considered to be one of the most characteristic manifestations of frozen shoulder [1, 3]. The eventual thickening of the CHL combined with its dense fibrous structure causes increased ER restriction [3, 9]. A recent study showed that the elasticity of the patellar tendon significantly decreased in healthy older subjects [27]. On the other hands, the elasticity of the CHL at the surface of the SSC increased with increasing age in the healthy participants in this study. These changes in the elasticity of tendons and ligaments associated with aging may reflect the aging process in many body parts.

Only one study that used SWE to evaluate CHL has been reported in patients with adhesive capsulitis, which showed that the surface of the CHL in the SSC on the affected side was thicker and stiffer than on the unaffected side [12]. There were no differences in the thickness or elastic modulus of the CHL between the dominant and the non-dominant shoulders in the neutral position under maximal ER in healthy subjects. These findings were consistent with our results [12]. In previous studies, the elasticity of the CHL in healthy subjects was greater than what we observed in our data. This could be explained by different measurements and protocols. A measurement taken closer to the muscle attachment site might result in higher CHL elasticity measurements, which would be more consistent with those previous reports [12].

This study indicated that the elasticity of the CHL is directly related to the aging process regardless of shoulder dominance. This indicates that dominance-related differences are less likely to occur in response to repetitive micro traumas sustained from prior athletic activities. In the lower extremities, the semitendinosus muscle tendons in men were stiffer than those in women based on SWE evaluations [28], which is contrary to our results. This could be explained by a difference in measurement locations. Previous reports stated that female subjects in general had significantly greater ROMs compared to male subjects [5], which could be explained by differences in joint laxity related to muscle mass. This principal exception to this explanation is at the glenohumeral joint.

The limitations to this study are as follows: (1) absence of arthroscopic or histological evaluations, (2) absence of frozen shoulder comparisons, (3) absence of ROM and laxity evaluations, (4) non-exclusion of degenerative joint diseases based on imaging, (5) difficulty in assessing tissue hydration and flexion based on age within the scope and technical ability of our testing procedure adopted for this research protocol, and (6) focus on a specific CHL region of interest near the coracoid process.

CONCLUSION

CHL elasticity generally increased with age. Elasticity of the CHL in the 30° ER position was greater and correlated more strongly to the elastic modulus compared that in the neutral position. An increase in the elasticity of the CHL is one of the many age-related changes faced by healthy individuals. Further research is needed to evaluate the relationships between age-based pathological changes in CHL elasticity, and how those relationships progressively relate to frozen shoulder diagnoses.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The study protocols were approved by the institutional review board of the Iwate Prefectural Central Hospital (approved number: 2455).

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

Both studies that originated the data used in the present secondary data analysis were conducted in accordance with the standards of the responsible ethic committee and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 and 2008.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.